Chatbots

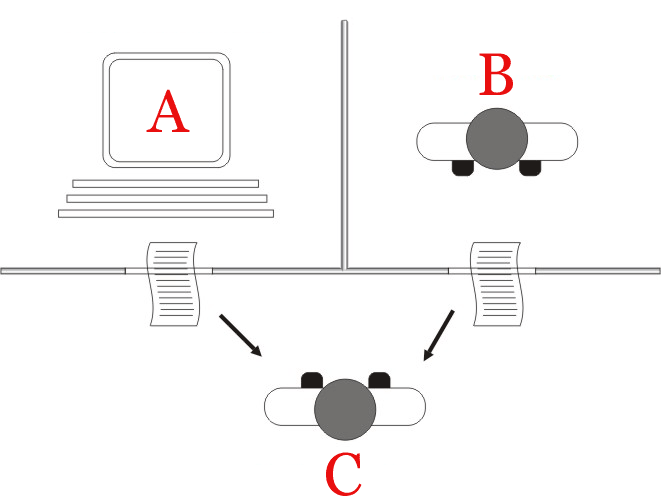

A chatbot, simply defined, is a computer program designed to simulate conversation with a human user.

In a 1950 paper titled “Computing Machinery and Intelligence” computing pioneer Alan Turing proposed his famous test, the so-called Imitation Game, often called simply the Turing Test.1 In this paper he substitutes the question of “can machines think?” with the problem of whether, under certain conditions, a human interrogator can differentiate between a computer and a person using technologically mediated conversation. Engaging only in dialogue, can a person tell whether his or her interlocutor is a human or a machine simulating human consciousness?

Turing’s paper was a landmark in the development of artificial intelligence and has spurred the development of thousands of so-called Turing Bots, otherwise known as chatterbots or chatbots. These include generalized chatbots such as Jabberwacky and Mitsuku and more domain specific programs such as ELIZA (see below). Other, increasingly pervasive examples include conversational agents Alexa and Siri whereby chat becomes the user interface. We might too think about the prevalence of CAPTCHA, a reverse Turing Test designed to establish that users are human (and avoid spam), across websites.2 The chatbot has become a common feature across digital technology today, and it is only growing more popular.

Turing helped to situate conversation at the heart of AI, and it remains the arbiter of success today. On the face of it this is an unproblematic development: Turing’s paper conceives of conversation as a turn-taking game, defined by clear rules of engagement. Seemingly, for computer engineers, conversation poses challenges in the form of natural language processing but is a problem modeled in terms of dematerialized communication theory.

Yet, conversation also resists such modeling in interesting ways. It is open-ended, context specific, and codes are culturally dependent. We think of conversation as embodied and embedded, with the meaning it constructs as intertwined with gesture, tone, interaction, and rhythm. Moreover, conversation has a long association not only with the critical public sphere but with aesthetics: with the French intellectual salons, painting’s “conversation pieces” or the Anglo-American tradition of the “art of conversation,” that reaches its apex in the novels of Henry James and Edith Wharton. In utilizing conversation, Turing might be arguing for the potential universality of machine intelligence, but his test also gestures towards the ultimate problem of computation: programming for the effects of bodies and culture.

Given use of chatbot interfaces is becoming commonplace – if faddish3,4 – I argue that it is important that cultural critics engage with them. They require, like machine translation, a theory of language. They also model a particular theory of interaction. Unlike a cybernetics model of communication, chatbots demand that we think about reception: how messages are received and interpreted.5 Analyzing the theories and models that are encoded in these programs and those that users bring with them can be very informative; indeed, the designer of the first digital chatbot introduced it explicitly as a program “For the Study of Natural Language Communication Between Man and Machine.”6

Similarly, as we rely increasingly on these interfaces – sometimes unawares – we need to think about the implications for our world. In the European and Anglophone sphere we place a heavy emphasis on communication between peoples as being a key feature of the political, public, and private spheres.7 How transformations wrought by mass media technologies in the twentieth century have affected communication is a central concern of many scholars across the humanities and social sciences. Chatbots clearly fall into this longer trajectory, but they also expose new fault lines in historic distinctions between humans and machines – as the abundant scholarship around trans- and posthumanism indicates.8,9 What does it mean to talk to, rather than have your communication mediated by, a program? Following N. Katherine Hayles and Mark Hansen, how might we think about human-nonhuman communicative assemblages? If we want to insist on a distinction between conscious and nonconscious communicative practice, what terms and definitions might we use? As bots, and indeed even chatbots, increasingly begin to communicate with other bots, what might this mean for our (anthropocentric) conception of communication in the political, cultural, and ethical realms?

In addition to these more general questions, study of chatbots, and communication in an age of automation, has implications for literary scholars. The processes of writing, reading, and analysis are no longer necessarily human acts aimed at other humans – as Clare Brant’s horse bot and discussion of animal selfies illustrate. Such interactions might well involve elements of automation and programming. If a computer program produces lines of poetry (as is the case in some of J. M. Coetzee’s early experiments), we might well ask not only where creativity is located in the process, but whether we need to expand the concept of creativity itself to cover nonhuman agency? We might further ask if a computer program – a chatbot – can engage in self-presentational forms and practices.

Chatbots, like any technology, are designed. The potential for algorithms to exacerbate inequalities has been the topic of important work by scholars such as Simone Browne, Virginia Eubanks, Cathy O’Neil, and Shoshana Zuboff.10,11,12,13 Literary scholars’ skills in critique become vital in this context: exploring the cultural assumptions inhering in these programs and their real-world applications, just as we explore those inhering in traditional cultural texts and objects.

Endnotes

- A. M. Turing, “Computing Machinery and Intelligence,” Mind LIX, no. 236 (October 1, 1950): 433–60, https://doi.org/10.1093/mind/LIX.236.433. ↩

- CAPTCHA has also received criticism from disability activists from an accessibility standpoint. ↩

- See, for example Robert Dale, “The Return of the Chatbots,” Natural Language Engineering 22, no. 5 (September 2016): 811–17, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1351324916000243. ↩

- Also Will Knight, “10 Breakthrough Technologies 2016: Conversational Interfaces,” MIT Technology Review, accessed June 12, 2019, https://www.technologyreview.com/s/600766/10-breakthrough-technologies-2016-conversational-interfaces/. ↩

- See N. Katherine Hayles, How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999). 54–56. For a fascinating discussion of cyberneticists’ battles over how to conceive of information theory: departing from the Shannon-Weiner model, Donald MacKay’s model “triangulated between reflexivity, information, and meaning” (p. 56). ↩

- Joseph Weizenbaum, “ELIZA: A computer program for the study of natural language communication between man and machine,” Communications of the ACM 9, no. 1 (1966): 36–45. 36. My italics. ↩

- John Durham Peters, Speaking into the Air: A History of the Idea of Communication (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999). ↩

- See, for example Cary Wolfe, What Is Posthumanism? (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011). ↩

- Also N. Katherine Hayles, How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999). ↩

- Simone Browne author, Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness / Simone Browne. (Durham: Duke University Press, 2015). ↩

- Virginia Eubanks, Automating Inequality: How High-Tech Tools Profile, Police and Punish the Poor (New York: St. Martin’s, 2018). ↩

- Cathy O’Neil, Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy (London: Penguin Books, 2018). ↩

- Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power (New York: Public Affairs, 2019). ↩

Bibliography

- Dale, Robert. “The Return of the Chatbots.” Natural Language Engineering 22, no. 5 (September 2016): 811–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1351324916000243.

- Eubanks, Virginia. Automating Inequality: How High-Tech Tools Profile, Police and Punish the Poor. New York: St. Martin’s, 2018.

- Hayles, N. Katherine. How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999.

- Knight, Will. “10 Breakthrough Technologies 2016: Conversational Interfaces.” MIT Technology Review. Accessed June 12, 2019. https://www.technologyreview.com/s/600766/10-breakthrough-technologies-2016-conversational-interfaces/.

- Simone Browne author. Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness / Simone Browne. Durham: Duke University Press, 2015.

- O’Neil, Cathy. Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy. London: Penguin Books, 2018.

- Peters, John Durham. Speaking into the Air: A History of the Idea of Communication. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999.

- Turing, A. M. “Computing Machinery and Intelligence.” Mind LIX, no. 236 (October 1, 1950): 433–60. https://doi.org/10.1093/mind/LIX.236.433.

- Weizenbaum, Joseph. “ELIZA: A computer program for the study of natural language communication between man and machine.” Communications of the ACM 9, no. 1 (1966): 36–45.

- Wolfe, Cary. What Is Posthumanism? Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011.

- Zuboff, Shoshana. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. New York: Public Affairs, 2019.