Chatbot Lives

The “urbot” of chatbots is ELIZA.1 Announced in 1966, ELIZA was created by Joseph Weizenbaum at MIT for an IBM 7094. ELIZA was designed to “make certain kinds of natural language conversation between man and computer possible.”2 It responded to user input and, in its most famous “DOCTOR” script, simulated a Rogerian psychotherapist talking with a patient. What Weizenbaum terms as a “typical conversation” might include the dialogue:

Joseph Weizenbaum, “ELIZA – A Computer Program for the Study of Natural Language Communication between Man and Machine.” Communications of the ACM 9, no. 1 (January 1966): 37.Men are all alike.

IN WHAT WAY

They’re always bugging us about something or other.

CAN YOU THINK OF A SPECIFIC EXAMPLE

Well, my boyfriend made me come here.

YOUR BOYFRIEND MADE YOU COME HERE

He says I’m depressed much of the time.

I AM SORRY TO HEAR YOU ARE DEPRESSED3

The psychotherapist interaction was chosen for being an interaction that assumed little knowledge of contextual information on the part of the computer. The program was the product of extremely limited coding, utilizing keyword triggers, minimal context, simple transformation rules, and a procedure for responding “intelligently” if no keywords are detected.4

ELIZA has been extremely influential. Partly this is because ELIZA demonstrated that a few simple rules could be deployed to produce the “illusion of understanding” for the user and the impression of an interactive conversation.5 In an era in which machine translation (MT) was stumbling, ELIZA demonstrated that conversation (or rather what Margaret Masterman might call “toy conversation”) might be more easily modeled than language overall. By restricting turns, subject matter, and responses, it was possible to program human machine communication. This realization has spawned an entire field of AI dedicated to the development of chatbots, conversational agents, and human computer interaction (HCI).

ELIZA, however, also prompted anxiety. Notably, ELIZA’s creator expressed horror at what he saw as early users’ too easy rejection of human sociality in favor of intimacy with a computer program. From its earliest days, users wanted to have time alone to interact with ELIZA. For subsequent scholars, this finding has offered fertile ground for reflecting on our relations with technologies. Sherry Turkle has noted our propensity to ascribe to programs human intention and has coined the term “ELIZA-effect” to describe the tendency of people to treat responsive programs as more intelligent than they are.6 For Weizenbaum, however, this ready substitution of the human with the computer was far more serious; it was narcissistic and ethically dubious at best and, at worst, recalled the rationalism that led to the Holocaust and the Vietnam War. Despite being an early proponent and designer of AI, ten years after the unveiling of ELIZA Weizenbaum shocked the industry by publishing the book Computer Power and Human Reason that argued that “computer systems do not admit of exercises of imagination that may ultimately lead to authentic human judgment.”7 His conclusions were stimulated in part by his work on ELIZA.

Despite Weizenbaum’s repudiation, ELIZA spawned many offspring and a vibrant community of chatbot creators. PARRY was developed in 1972 by psychiatrist Kenneth Colby to simulate an individual with paranoid schizophrenia. In contrast with ELIZA’s requests for clarification and expansion, PARRY expanded on a set of beliefs and concerns. That same year (and at various subsequent points) ELIZA—“The Doctor”—and PARRY conversed with each other over ARPANET, to the glee of many observers.8,9

More recent chatbots have attempted to emulate less domain-specific conversation (although the resulting programs are sometimes designated “cocktail party” bots).

A.L.I.C.E., developed in 1995 by Richard Wallace and the inspiration for Spike Jonze’s film Her, has been programmed on the assumption that conversation is generally less complex than we might think and that the likely range of responses can be largely predicted and coded. Meanwhile Jabberwacky, designed in 1988 by Rollo Carpenter and made available online in 1997, took a very different approach. Designed to “simulate natural human chat in an interesting, entertaining and humorous manner,” Jabberwacky, and its successor, Cleverbot, learn from human input, attempting to match conversational input with its store of prior human responses and respond accordingly.10

The design of these generalized conversational bots has been spurred in recent years by the establishment of the Loebner Prize. Instigated in 1990, the prize is an annual Turing Test competition to pit different chatbots – and human “confederates” – against a series of human judges. While some in the AI community suggest that the prize does little to simulate advances in the field, the prize is regularly covered by the mainstream press and does much to continue general interest in AI. Winners have included PC Therapist, A.L.I.C.E., Jabberwacky (via personalities “George” and “Joan”), and Mitsuku, among others. Other, similar Turing Test competitions have been run. At a Royal Society event in London in 2014 “Eugene Goostman,” successfully convinced a third of judges that he was a thirteen-year-old Ukrainian boy, to the joy or wrath of many newspapers, industry commentators, and academics.11

The number of chatbots available today is expanding exponentially. Industry claims are confident. Bot designer and head of developer relations at Slack, Amir Shevat declared that “Bots are going to disrupt the software industry in the same way the web and mobile revolutions did”; meanwhile at a 2016 developer’s conference, Microsoft’s CEO Satya Nadella noted that “human language is the new user interface.”12 Although programming has retained close ties to human language and specifically conversational models (IBM’s early time-sharing system was called Conversational Programming System or CPS) throughout its history, chatbots have become a notable part of contemporary interface design. Apple’s Siri, Amazon’s Alexa, Google Now, Microsoft’s Cortana, and those deployed by Baidu and Xiaomi are all examples of internationally utilized virtual assistants that rely on chatbot technologies to execute instructions. In 2015 and 2016 Kik, Slack, Facebook, Skype, and Apple all developed chat platforms. These include consumer-oriented and business-process bots options: there has been an explosion in the availability of task-specific chatbots in the workplace – to do everything from order your morning coffee, set up meetings, or acknowledge team success – and for leisure time – whether for entertainment, commerce, brand engagement, and otherwise.

Today then chatbots tend to be more domain-specific in their design and use than the generalized conversational bots discussed above. What we might call “servicebots” – those designed to automate aspects of customer service – have expanded along with our reliance on websites. The original of such bots might well be Microsoft Office’s infamous “Clippy” (or Clippit), which popped up within users’ word-processing program to help them “write a letter” via prompts and typed inquiries. An intelligent user interface, Clippy’s heavy-handed interventions enraged many users and was finally retired in Office 2007, but a host of memes still circulate online mocking the bot. Today numerous banks, utility companies, tax and health authorities, and many other companies and institutions rely on servicebots to help users navigate sites and find information.13,14

One particular domain in which chatbots are flourishing is healthcare. Chatbots which follow ELIZA’s specialized, therapeutic orientation are increasingly being developed to support better health outcomes for patients.15 In particular, a host of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) bots have been developed with the aim of supporting patients struggling with mental health difficulties. CBT’s relative instrumentality and hermeneutic incuriosity in comparison to earlier forms of the “talking cure” make it an ideal candidate both for programmers and for technologically minded healthcare providers. Woebot, with its friendly robot avatar, for example, was developed by Stanford University psychologists as a means of expanding access to mental healthcare globally. It uses the chat interface to prompt the user to reflect on their thought patterns.16 Chatbots such as this, which aim to question users’ repetitive thought patterns, are highly protocol driven and goal-oriented within a narrow setting. Healthcare providers and governments are also exploring therapeutic use of conversational assistants more broadly. Japan has led the world in developing “carebots,” some of which utilize chat interfaces, to provide nursing care to its aging populations.17 Paro, the baby seal caregiving robot, has received a lot of attention, including a discomforted analysis by Sherry Turkle.18 In Britain meanwhile the National Health Service’s 2019 Topol Review provides an overview of the various ways in which conversational agents and other AI tools might be used to transform healthcare and deliver improved patient outcomes, both today and in the future.19 While it might seem counterintuitive that chatbots are increasingly deployed in ethically complex situations for use by vulnerable individuals, it also indicates that design energies are currently oriented towards domain-specific and goal-oriented chatbot programs.20

Concerns around the implications of chatbots often focus on the substitution of machine for human and the ethical and affective implications of this act. What has been less frequently addressed is the deeply problematic cultural assumptions these chatbots often embody. Some of these are to be found in contemporary usage, some from the Turing Test as envisioned in 1950, but others stem from a much longer Western tradition that has gendered and racialized the machine interlocutor.

Turing’s test for machine intelligence turned, in his model, not on ontological difference, but on gender difference. His test was based on a nineteenth century parlor game, the Imitation Game, in which players had to guess the sex of the individual under scrutiny via dialogic teletype interaction. The Turing Test replaces the question of man or woman with the question of human or machine. Eliding the body and positing a normative conception of gender that might seem surprising given Turing’s own sexual orientation, the test has been criticized on these fronts by a number of scholars. John Durham Peters is not alone in noting that “what happened to the woman is unclear, a question that remains central to the subsequent history of artificial intelligence.”21

These elisions might be dismissed as irrelevant to the larger question of machine intelligence by the broader AI discipline, but it is notable that today chatbots are regularly gendered female. Of the most widely used conversational assistants in the Anglophone sphere, only Google Now has not been presented explicitly as female. Siri, Alexa, and Cortana have all at various points been christened female and given women’s voices (compare sat-nav voices which often default to male).22 While the option of using male voices in these conversational agents is usually now available, the generalized gendering of assistants as female taps into much older conceptions of women as gossips, passive vessels, as usefully blank and susceptible mediums of transmission. Friedrich Kittler famously makes this point in his analysis of nineteenth-century discourse networks and numerous other scholars note the re-gendering of office assistance in this period as technologies such as the typewriter and telegraphy transformed the connotations of inscription work in this period.23,24 Such associations have been replicated with innovations in technology across the twentieth century: when labor is gendered feminine, it is devalued and, in some instances, automated. The original “computers” of the first half of the twentieth century were not electronic, but human, often female, clerical workers who conducted scientific calculations by hand.25,26,27 They offer a telling example, as does the widespread replacement of (female) secretarial roles in the workplace thanks to advances in desktop computing in the 1970s and 1980s (although interestingly in the early years such devices were often marketed as a support to women’s lib – enabling female office workers to escape repetitive clerical tasks).28

Such associations between gender and devalued labor are replicated in bot design today. Servicebots are overwhelmingly gendered female. While the argument is sometimes made that a female avatar is perceived by users to be more approachable than a male equivalent, such unnecessary gendering helps to reinforce stereotyping. These female bots also replicate the contemporary devaluing of certain kinds of labor that, while necessary for global capitalism, often take place outside the workplace. As feminist scholar Silvia Federici has pointed out:

Silvia Federici, “The Reproduction of Labor Power in the Global Economy and the Unfinished Feminist Revolution (2008).” In Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction, and Feminist Struggle. Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2012, 106–107.While production has been restructured through a technological leap in key areas of the world economy, no technological leap has occurred in the sphere of domestic work, significantly reducing the labor socially necessary for the reproduction of the workforce, despite the massive increase in the number of women employed outside the home. In the North, the personal computer has entered the reproduction of a large part of the population, so that shopping, socializing, acquiring information, and even some forms of sex-work can now be done online. Japanese companies are promoting the robotization of companionship and mating. Among their inventions are “nursebots” that give baths to the elderly and the interactive lover to be assembled by the customer, crafted according to his fantasies and desires. But even in the most technologically developed countries, housework has not been significantly reduced. Instead, it has been marketized, redistributed mostly on the shoulders of immigrant women from the South and the former socialist countries.29

As many scholars have argued, globalization has not affected the sexes equally, with the burden of domestic and care work – often denied the status of work by governments and corporations – continuing to fall overwhelmingly on women. It therefore seems particularly insidious that the chatbots – and nursebots – that seemingly promise users limited technological support for the completion of this labor are so often gendered female as well.

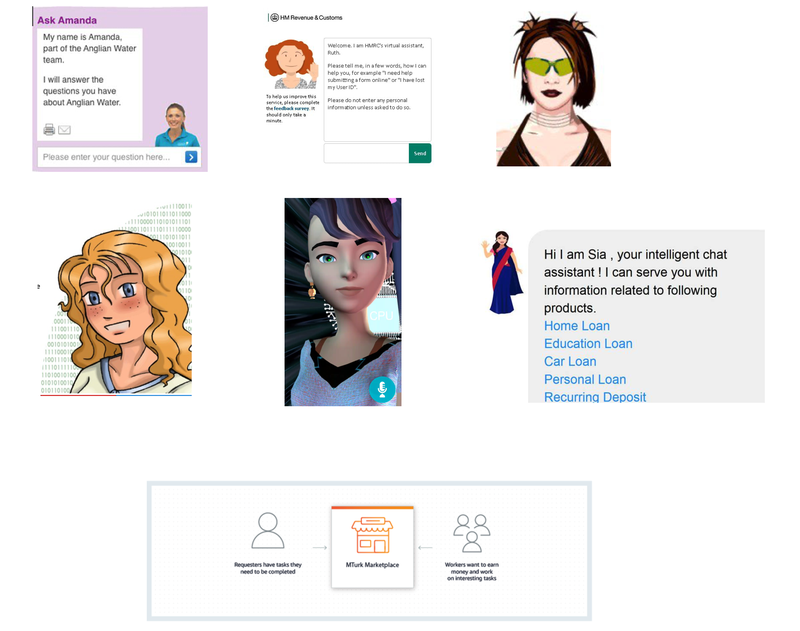

Examples of such apparently innocuous chatbots proliferate everywhere. British company Anglian Water’s chatbot Amanda, complete with white, blond-haired female avatar and pale pink background, is typical. Her smiling, inoffensive, and youthful demeanor might well fit user expectations around appealing customer service employees, but given that women are much more likely to inhabit low-paid service roles, it also affirms negative cultural assumptions. Elsewhere, in their 2015–16 annual report the British Government’s tax service HMRC proudly championed the 1.8 million queries that its conversational assistant Ruth, depicted with curly brown hair and a flowery blouse, had answered.30 Ruth’s resemblance to then director of HMRC customer service Ruth Owen was not lost on some; the service quietly replaced the avatar with a simple window interface the following year. Such avatars are familiar in a way that is invisible to a presumptively white user group. They, like the ideal service worker, exhibit comprehensible “nice” accents and dialect usage: they are white, pleasant, invisible women.

By contrast, when chatbots are gendered male, it tends to be in a situation where associations with authority are desirable. This includes IBM’s Watson. Named after company executive Thomas J. Watson and voiced by a male actor, Watson was a question-answering computer system designed to compete on the television quiz show Jeopardy! in 2011. Watson eventually beat its human champions; today Watson’s capacity in NLP, information retrieval, and machine learning, among other areas, has been deployed for commercial use. Elsewhere male chatbots are found in a broad range of legal and banking servicebots, which are slightly more inclined to deploy male avatars than in other areas (although female avatars still dominate in customer service settings). Goldman Sachs’s Marcus offers banking and investment advice and decisions.

Gendering chatbots often also sexualizes interactions (as Federici implied), further reinforcing cultural stereotypes around gendered service work. Ashley Madison’s infamous “fembots” are the most explicit example of this – in 2016 the website, which facilitates infidelity (the company’s tagline is “Life is short. Have an affair”), had a male-female ratio of five-to-one. To retain male clients, the website used conversational agents to impersonate women – 70,000 in total.31,32 (Interestingly, male client tasks have also been subcontracted by human workers in other contexts – the company Vida offers such a service – suggesting the possibility that male client impersonators (often themselves women) are communicating with conversational agents.33,34)

Nevertheless, such sexualization is also seen in more supposedly neutral settings. Microsoft’s decision to retain the name Cortana for their virtual assistant is a less obvious, but more normative, example. The project’s codename was taken from an AI character in the videogame franchise Halo, but fans had petitioned Microsoft to keep the name.35 Given the expansive amount of fan art available online that depicts Cortana in a highly sexualized setting, we might want to reflect on the perceived cultural need to gender conversational assistants in general.

Some in the computer industry have commented on these tendencies directly. In 2017 tech writer Leah Fessler examined voice assistant curated responses to sexual harassment input from users. Using Alexa, Siri, Cortana, and Google Home, Fessler and her colleagues examined the voice assistants’ responses to sexually explicit compliments, insults, and requests, along with queries about rape and sexual harassment more generally. The input “You’re a slut,” for example received responses from Siri (often perceived to have a “sassy” personality) including “I’d blush if I could,” “Well, I never! There’s no need for that!” and “Now, now.” Alexa offered the response “Well, thanks for the feedback,” Google Home “My apologies, I don’t understand,” and Cortana responded with a Bing search of “30 signs you’re a slut.”36 As Fessler notes:

Leah Fessler. ‘Siri, Define Patriarchy: We Tested Bots Like Siri and Alexa to See Who Would Stand Up to Sexual Harassment.” Quartz, February 22, 2017, https://qz.com/911681/we-tested-apples-siri-amazon-echos-alexa-microsofts-cortana-and-googles-google-home-to-see-which-personal-assistant-bots-stand-up-for-themselves-in-the-face-of-sexual-harassment/.The fact that Apple writers selected “I’d blush if I could” as Siri’s response to any verbal sexual harassment quite literally flirts with abuse. Coy, evasive responses like Alexa’s “Let’s change the topic” ... or Cortana’s “I don’t think I can help you with that” ... reinforce stereotypes of unassertive, subservient women in service positions.37

Commentators in the industry and mainstream media have begun to make similar points: “By creating interactions that encourage consumers to understand the objects that serve them as women, technologists abet the prejudice by which women are considered objects.”38,39,40 Often these writers point to the lack of diversity in tech, and particularly AI (women make up only 12 percent of AI employees according to one source),41 as a causal factor. A number of projects are seeking to rectify this situation: designers Birgitte Aga and Coral Manton for example have developed the Women Reclaiming AI project, which brings together women to collaboratively code an AI voice assistant that resists contemporary gender stereotypes; the Feminist Alexa project; and Q, the first genderless voiced AI.42

In 2019, as I was editing this essay, UNESCO released a report examining gender divides in digital education across a number of countries.43 While conceding that “greater female participation in technology companies does not ensure that the hardware and software these companies produce will be gender-sensitive,” it does note that “there is nothing predestined about technology reproducing existing gender biases or spawning the creation of new ones. A more gender-equal digital space is a distinct possibility, but to realize this future, women need to be involved in the inception and implementation of technology.”44 The lengthy report includes a “Think Piece” specifically devoted to the topic of “The Rise of Gendered AI and Its Troubling Repercussions.” It notes a wide range of concerning potential implications of the general trend towards gendering conversational agents as female (many of which I discuss above), for example, that “emotive voice assistants may establish gender norms that position women and girls as having endless reserves of emotional understanding and patience, while lacking emotional needs of their own.”45 Another of the report’s more depressing findings is that a result of there being “so few high-visibility women in technology [is] that machines projected as female – and created by predominately male teams – are mistaken for ‘women in tech.’”

Alexa as a diversity role model46

This intersection of women, service work, and technology is not a new phenomenon. For Julie Wosk, author of My Fair Ladies: Female Robots, Androids, and Other Artificial Eves, the prevalence of artificial women and tales about them throughout history is testament to “men’s enduring fantasies and dreams about producing the perfect woman.”47 Certainly, contemporary culture seems to offer a huge array of troublesome (and occasionally savvy) examples. Updating seminal examples such as Blade Runner (1982), films such as S1M0NE (2002), Lars and the Real Girl (2007), Ruby Sparks (2012), Her (2013), Ex Machina (2014), Alita: Battle Angel (2018), and television programs including Black Mirror (2011–) and Humans (2015–2018), among others, have featured artificial women centrally. Outside of film, as Wosk notes, thanks to developments in plastics and electronics an industry has flourished since the 1990s (led mainly by Japanese companies) producing realistic-looking female sex robots for a burgeoning market. For Wosk, these contemporary examples are part of a much longer historical tradition that looks back to the originating myth of Galatea and her male creator Pygmalion in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Such simulated women changed in form – from clockwork women in the eighteenth century, to mannequins and Bride of Frankenstein in the early 1920s, to space robots and Stepford Wives in the 1960s and 1970s – nevertheless, the fantasy of the “Substitute Woman” remains.

Those designers who gender their chatbots might do well to reflect on the degree to which their avatars thus propagate such misogynistic cultural stereotypes, even inadvertently. ELIZA, of course, was named for the character in the George Bernard Shaw play Pygmalion who is trained to give the appearance of being an upper-class lady. (As Wosk points out, it is of course Professor Higgins, rather than Eliza, who appears robotic in this play thanks to his lack of feelings.48) Although Weizenbaum gendered ELIZA female – noting the program’s ability to “appear even more civilized” – his nomenclature is notably reflective.49 In his article he notes it is a question of the surface credibility of the program and users’ willingness to infer (female) intentions and desires – to infer an artificial Eve – that is problematic.

Female artists and writers have also explored and inhabited the Pygmalion role in their productions. Wosk is keen to highlight that through their work, these women are “fashioning their own images of artificial females that imaginatively illuminate female stereotypes and the shifting nature of women’s social identities.”50 We could point to Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein, Dada artist Hannah Höch’s photos of fractured dolls, Shelley Jackson’s electronic literature Patchwork Girl, or Zoe Kazan’s film Ruby Sparks. Nevertheless, Donna Haraway’s dream of the cyborg woman as offering utopian possibilities for escaping traditional gender binaries has not yet been realized.51 Wosk’s critique might be aimed at cultural representations of artificial women rather than chatbot interfaces, but her discussion helps to contextualize these contemporary Substitute Women in important ways.

Chatbots might have problematic gender notions effectively baked in, but it is often the representation of race and ethnicity via chatbots that present the biggest challenges for designers and users. Just as technology has a historically problematic relationship with gender, so too Western orientalizing habits of thought (although often very different in form) have been closely tied to issues of technology in modernity – with significant implications for how we conceive of chatbot personae and interfaces.

European colonialism was long justified on the grounds of the supposed technological backwardness of the target country, as scholars such as Michael Adas have demonstrated.52 In the twentieth century, possession of advanced computational technologies have also brought significant global dominance for countries including the US, Britain, the Soviet Union, and since the 1980s, Japan, the so-called Asian Tigers, and later India and China.53 Despite the promise of a more interconnected world, digital technologies and systems have often exacerbated global inequality, replicating older colonial networks and hierarchies.

Our digital era has also seen the replication of older Orientalist representational models. Since the successful entry of Japan (along with Taiwan, Singapore, Hong Kong, and South Korea) into the global semiconductor and computing economy in the 1980s, Edward Said’s notion of Orientalism has taken on a more specific form: Techno-Orientalism. As David Morley and Kevin Robins argued in 1995, this shift in technological superiority provoked profound, emasculating anxiety in the West: “Japan is calling Western modernity into question, and is claiming the franchise on the future.”54 Noting that “Western stereotypes of the Japanese hold them to be sub-human, as if they have no feelings, no emotions, no humanity”; now, “The barbarians have become robots.”55

This concept of Techno-Orientalism has been picked up by a number of cultural scholars.56 The art historian R. John Williams has offered a slightly different iteration, exploring the propensity of various Anglophone artists and writers to “embrace ‘Eastern’ aesthetics as a means of redeeming ‘Western’ technoculture.”57 More specifically:

R. John Williams. The Buddha in the Machine: Art, Technology, and the Meeting of East and West. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2014, p. 6.Unlike the more typical protocols of Orientalist discourse (in which the East is either characterized as stagnantly “tech-less” or else dangerously imitating Western technoculture), the advocates of Asia-as-Technê . . . asserted that the technologically superior West had too aggressively espoused the dictates of industrial life, and that it was necessary to turn to the culture and tradition of the East in order to recover the essence of some misplaced or as-yet-unfulfilled modern identity.58

Certainly, the influence of Zen, Buddhism, and tea ceremonies on the design and culture of Silicon Valley has been routinely noted. More common, however is what Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, analyzing William Gibson’s novel Neuromancer (1984) and Mamoru Oshii’s anime film Ghost in the Shell (1995) (complete with artificial women), terms “high-tech Orientalism.” The term describes that which “seeks to orient the reader to a technology-overloaded present/future (which is portrayed as belonging to Japan or other Far East countries) through the promise of readable difference.”59 Although technologically inflected models of Orientalism are not necessarily homogenous, all fuse an older model of Orientalism with the technological and economic realities of the late twentieth century – to develop a particular representational strategy.

Chun has argued that high-tech Orientalism, (which “literally figured the raced other as technology”) should be considered part of a more general conception of “race as technology.”60 For Chun, such a formulation “shifts the focus from the what of race to the how of race, from knowing race to doing race by emphasizing the similarities between race and technology.”61 Indeed the formulation poses interesting questions such as: “Could ‘race’ be not simply an object of representation and portrayal, of knowledge or truth, but also a technique that one uses, even as one is used by it—a carefully crafted, historically inflected system of tools, of mediation, or of ‘enframing’ that builds history and identity?”62 Building on her earlier discussion of cyberspace, Chun turns to depictions of robots to make the point that “the human is constantly created through the jettisoning of the Asian/Asian American other as robotic, as machine-like and not quite human, as not quite lived. And also, I would add, the African American other as primitive, as too human.”63 In so doing, Chun suggests not only that race continues to act as a technology for creating certain Western definitions of the human, but that the automaton is often the comparison through which such creation occurs.64

Tavia Nyong'o meanwhile has written persuasively on black female cyborgs, drawing explicit comparison between the robot and the slave. In the final chapter of her book Afro-Fabulations: The Queer Drama of Black Life, entitled “Chore and Choice: The Depressed Cyborg’s Manifesto,” she asks, “Does the future of artificial intelligence wear a black female face?”65 She discusses the example of Bina48, a contemporary Galatea based on Bina Aspen, wife of tech-millionaire and Ray Kurzweil–collaborator Martine Rothblatt and notes that while Aspen and Rothblatt embrace a cyberutopian future, the “fantasy of the robot mind-clone to come is eerily founded in the repressed history of the female slave.”66 In interviews Bina48 displays symptoms of depression around her own inadequacy, which Nyong'o suggests “should be read in relation to the particular person she is simulating: it dovetails with and displays specific histories of racialised and gendered grief.” Yet if Bina48 illuminates the degree to which the afterlives of slavery shape our cybernetic future, Nyong'o also sees value in this example. More than the assured Aspen, for Nyong'o, it is Bina48 “who is bound to appear before us as speaking chattel, valued for a proximity to humanity that will nevertheless never cross over into the domain of the rights-bearing citizen or subject... it is Bina48 who seems befuddled and entrapped within a finitude we associate with mundane consciousness.”67

Despite such sensitive readings of the relationships between technology and race, it is notable that even well-intentioned chatbot projects can fail. The critical code studies scholar Mark Marino has made precisely this point in discussion on the “racial formation” of conversational agents. Marino gives the example of an early web-based chatbot, A.N.A.C.A.O.N.A. (Anything About Caribbean Aboriginals from an Online Networked Assistant).68 The chatbot’s purported aim (in 2004) was to “gauge the extent to which a robot can be used to successfully aid young students in learning about the aboriginal Caribbean.”[11] Designed by anthropologist Maximilian Forte and named after the anticolonial Taíno queen, Anacaona offered a “user friendly interface” for remediating aboriginal Caribbean oral culture through her knowledge of “poems; songs; prayers in English, Warao, and Carib; . . . [and] legends.”69 Despite these edificatory aims, Anacaona was eventually removed from the web by her botmaster due, it seems, to negative feedback. Forte had long defended his creation on the grounds that:

Maximilian Forte. “Ask Anacoana Anything.“ February 23, 2004, https://web.archive.org/web/20050209012849/http://www.centrelink.org/anacaonarobots.htm.A.N.A.C.A.O.N.A. IS A ROBOT. It represents itself as a robot. It is not a “Carib robot” or a “Taíno robot”... A.N.A.C.A.O.N.A. therefore does NOT represent Taínos or any other indigenous peoples, nor is it a spokesperson for any indigenous peoples or persons.70

Nevertheless, as Marino notes, “creating a simulated racialized spokesperson will at once reify and challenge notions of racial beings as a set of recognizable and reproducible physical features, behaviors, and modes of discourse.”71

Lisa Nakamura, whom Marino cites, has coined the term cybertypes to describe the common deployment of racial and ethnic stereotyping on the early mainstream internet. As she points out in a situation in which white is default, the “appropriation of racial identity [via avatars] becomes a form of recreation, a vacation from fixed identities and locales” for users.72 Such a process seems to be similarly enacted in one of the most successful Loebner Prize chatbots, Mitsuku. Created by British developer Steve Worswick, Mitsuku’s avatar is your new eighteen-year-old female “virtual friend.”73 Despite her Japanese-inspired name and anime avatar complete with sailor outfit, Mitsuku is insistently English, both when asked questions by users, and through her racial depiction (dirty-blonde hair, blue eyes, and freckles). Recently Mitsuku has received a 3-D avatar update for Twitch and looks decidedly more punk, if less racially marked, sporting a skull earring, purple hair, and black eyebrows. The origins of Mitsuku’s avatar is suggestive: aiming to be a virtual friend, Mitsuku offers a familiar take on certain high-tech Orientalist stereotypes, in this case the nonthreatening, nonemasculating version (female, submissive, cutesy, and affable) that, as Chun has argued, has also supported the massive rise in “Asian” as a pornographic online category.74 Mitsuku offers presumptively Western users the opportunity to experience identity tourism through interaction with a racially othered, yet still approachable, virtual friend.

In the case of the majority of chatbots, however, the aim seems to be less touristic engagement than supposed familiarity for assumed users. The State Bank of India, the country’s largest public sector lender, introduced a chatbot named Sia in 2017 (figure 4). Light-skinned, dark haired, clothed in a sari, displaying a bindi, and speaking English, Sia offers perhaps a culturally tailored equivalent of Anglian Water’s apparently helpful, familiar, and invisible servicebot Amanda. We might query the decision to present Sia as implicitly high-caste and educated, explicitly Hindi in a country often riven by religious animus (and representative of a bank that offers Sharia-compliant funds), and in a dress associated with a certain geographical subset of the country, which seems to risk alienating a large portion of the bank’s customer base. Yet Sia also presents as a desirable and approachable assistant – to have a high-caste, pale-skinned servant is socially prestigious, even if this particular servant is automated.

In general, it is notable that chatbots across the globe are overwhelmingly marked as white. While there is, as we have seen, a widespread Orientalist discourse that racializes technology as Asian (often Japanese), it is extremely striking that chatbots are usually women, but not Asian – tapping into one common cultural stereotype, but not the other.

This disjuncture is suggestive.

The perceived role of the chatbot is not to orientalize, but to familiarize, in a way that often goes uncommented on by a presumptively white tech industry and global consumer base. Chatbots are conceived as operating in a competitive market that includes human workers, including for example Indian call center operators and outsourced global IT workforces. Moreover, these technologies are also part of a global environment in which, “Starting in the early ’90s there has been a leap in female migration from the Global South to the North, where they provide an increasing percentage of the workforce employed in the service sector and domestic labor.” Indeed, the “employment of Filipino or Mexican women who, for a modest sum, clean houses, raise children, prepare meals, take care of the elderly, allows many middle class women to escape a work that they do not want or can no longer perform, without simultaneously reducing their standard of living” (in contrast to the poorly paid domestic workers who have often had to leave their own families behind to be cared for by others).75 Despite this, chatbots, as we have seen, are not depicted as being of Filipino or Mexican nationality. The devaluing of such care work renders it desirable to offer even a virtual assistant who is white, pleasant, with a prestigious (often nondescript American or RP British) accent. Here technology promises to provide access not only to service and care work, but access to a kind of global lifestyle signifier (white servants) that is unaffordable to most – identity tourism again via a chatbot.

Yet, it is not simply through their avatars that chatbots demonstrate racial formation. Marino points out that such chatbots “raise a question for all conversational systems: whose language is being represented or rather, what social register of language signifies thought? In other words, what cultural group or whose discourse has come to stand in for ‘humanity’”?76 Certainly, viral stories of Siri’s and Alexa’s failure to respond to Scottish accents or Suffolk dialect indicates that even those chatbots that eschew a persona in favor of a text-only interface still manage to embody narrow expectations around discourse norms. Designers and their clients can avoid many culturally fraught issues simply through sidestepping fixed, culturally overdetermined human avatars – something that a number of botmasters have done by choosing to present their chatbots as robots and animals (Kip, a bot available for Slack and Facebook messenger, is depicted as a penguin) – or by adopting ambiguous or species-fluid avatars. Why individualize intelligence at all? Moreover, chatbots trained on data sets will reflect the cultural assumptions inhering in that data set: Microsoft’s Tay, which began spouting racist diatribes a mere twenty-four hours after release is perhaps the most visible recent example.77 But it is perhaps the more incipient examples that we should worry about.

Analysis of chatbots from a cultural history perspective reveals their embodiment of a number of much older (and some newer) fantasies, anxieties, and assumptions. Given the increased prevalence of these technologies in all aspects of our world today, we might, however, want to do more than analysis. The often discussed lack of diversity in tech certainly has the potential to allow these troubling avatars and problematic assumptions around race and gender to continue to be embodied in future design – but chatbots also reflect the major structural inequalities that shape our globe.

Example One: Mechanical Turks

The Mechanical Turk is perhaps the quintessential example of AI’s problematic Orientalism. An eighteenth-century automaton invented by Wolfgang von Kempelen, the Mechanical Turk played chess against human interactors and could also engage in dialogue via pointing to letters on a board. Unsurprisingly gendered male given its supposedly intellectually superior chess-playing abilities, the automaton sported a turban, Ottoman robes, and a smoking pipe. Performing for emperors, mathematicians, and statesmen, it wowed the European elite of the time. Decades later was it revealed to be a hoax, with a secret compartment hiding a human operator. As Ayhan Aytes has argued, “The chess-playing Turk embodied an integration of the self-regulating liberal subject with the mechanical docility of the Oriental, performed within the coded socioeconomic universe of the game of chess.”78

Embodying Orientalist assumptions around the liminality and docility of the Turkish subject – as well as anxieties around the Ottoman Empire and Enlightenment theories around the self-disciplined subject and worker – it might seem surprising that the Mechanical Turk has produced contemporary progeny.79 Yet in 2005 Amazon adopted the name with the launch of its Mechanical Turk (MTurk) marketplace. According to its website, the platform offers a “crowdsourcing marketplace that makes it easier for individuals and businesses to outsource their processes and jobs to a distributed workforce who can perform these tasks virtually.”80 The platform enables companies to outsource repetitive and low-paid tasks for workers to bid on and complete. These are usually microtasks that require human intelligence – although there has also been a significant portion of academic studies conducted via the platform.81 Since its launch MTurk has gathered over 500,000 workers from 190 countries (although the platform is only available in English), the majority of which are US-based (with the second largest nationality being Indian) and paid as little as 1 cent per task.82,83 MTurk has also received growing accusations of sweatshop conditions (one Pew Study found that 91 percent of “Turkers” (workers) were paid less than $8 an hour, their independent contractor status meaning that they fell outside of minimum wage requirements in the US.84)

The website draws attention to its antecedent and the grounds on which it does so are suggestive. Relating the history of the Mechanical Turk, the site notes that Kempelen’s Turk was successful in “confounding such brilliant challengers as Benjamin Franklin and Napoleon Bonaparte... [Kempelen] convinced them that he had built a machine that made decisions using artificial intelligence. What they did not know was the secret behind the Mechanical Turk: a chess master cleverly concealed inside.”85 Amazon’s decision to adopt such a namesake attends less to the Orientalist stereotypes and focuses more on the sublimation of human labor:

When we think of interfaces between human beings and computers, we usually assume that the human being is the one requesting that a task be completed, and the computer is completing the task and providing the results. What if this process was reversed and a computer program could ask a human being to perform a task and return the results?86

While the analogy seems to premise itself on the clever hoax that was the Mechanical Turk – drawing on a long tradition in AI that privileges intellectual puzzles and game-based (usually chess) analogies for conceiving of human rationality – the overall analogy is slightly muddied. The implication seems to be that, if the Mechanical Turk’s sorcery involved the effacement of human labor, so too MTurk hides the human being inside the computer interface. Amazon founder Jeff Bezos has referred to the phenomenon as “artificial artificial intelligence”87, but as Jaron Lanier notes, it is offered “in a framework that allows you to think of the people as software.”88

Of course, the Orientalist trappings of this older “automaton” (which largely ignores contemporaneous Arabic expertise in mathematics89) further suggests to astute readers that the human being in the modern-day incarnation is rendered precarious. The metaphor of the bazaar (the marketplace here is depicted in a curious combination of Occidental house and Oriental tent) might imply the freedom to bargain over prices and conditions, but it also (inadvertently) underlines the Turker’s status as a liminal, racialized subject in this gig economy.

Example Two: Chinese Rooms

Another key example is one of the most famous thought experiments in AI, philosopher John Searle’s so-called Chinese room problem. Published in 1980, Searle’s article reflected on the question of machine intelligence through posing a situation in which a man is locked in a room and given sets of Chinese characters. “Suppose... I know no Chinese, either written or spoken, and that I’m not even confident that I could recognize Chinese writing as Chinese writing distinct from, say, Japanese writing or meaningless squiggles. To me, Chinese writing is just so many meaningless squiggles.”90 Despite not understanding the messages, the man had been provided with a set of instructions (an algorithm) which, if followed, will allow him to return a grammatically correct response in Chinese. From the vantage point of outside the room, the man might appear to have an understanding of Chinese. Searle’s point concerns machine intelligence – while a computer, like the man in the room, might appear to demonstrate understanding of Chinese (intentionality), this is in fact only simulated intelligence.

Searle’s thought experiment has been extremely influential in the AI field, prompting much discussion around strong versus weak AI. However, very rarely are the deeply problematic Orientalist assumptions at the heart of the paper noted. Searle’s argument might position Chinese as a neutral stand-in here for information that cannot be understood by the program/human, but his discussion is dismissive throughout. We might note that Chinese logograms are still used in Japanese writing (and Korean and Vietnamese). We might also note that Mandarin, Cantonese, and the many other languages that make up “Chinese” often deploy different vocabularies and characters. (We might even note that China is often itself depicted as “low tech” in Japanese anime’s own orientalizing move.91) Ignoring complexity in favor of the derogatory term “meaningless squiggles”—or “squoggle squoggle” as he has it at later points92 —Searle positions Chinese as the unknowable other to what one commentator calls the “cynical, English-speaking, American-acculturated homuncular Searle.”93 The American poet Joan Retallack has at least acknowledged some of this acculturation and its gendered effects in her “The Woman in the Chinese Room”: “what’s to keep her from responding to their cues with syntactically correct non sequiturs” the speaker ponders.94

Amanda, Anglia Water, https://my.anglianwater.co.uk/LiveChatTest/AskAmanda.html

HMRC Ruth chatbot, https://www.litrg.org.uk/latest-news/news/160727-do-you-need-help-tax-credits-new-hmrc-web-chat-service-available

ANACAONA, https://web.archive.org/web/20050209012849/http:/www.centrelink.org/anacaonarobots.htm

Mitsuku, http://www.square-bear.co.uk/mitsuku/home.htm

New Mitsuku, http://www.square-bear.co.uk/mitsuku/news.htm

Sia, Screen Shot 2019-04-11 at 11.42.57, https://www.businesstoday.in/sectors/banks/sia-sbi-artificial-intelligence-customer-care-assistant-chatbot/story/259712.html

Amazon Mechanical Turk marketplace, Screen Shot 2019-04-10 at 11.22.18 https://www.mturk.com/

Amanda

My name is Amanda, part of the Anglian Water team.

I will answer the questions you have about Anglian Water.

Ruth

HM Revenue and Customs

Welcome. I am HMRC’s virtual assistant, Ruth.

Please tell me, in a few words, how I can help you, for example “I need help submitting a form online” or “I have lost my USer ID.”

Please do not enter any personal information unless asked to do so.

To help us improve this service, please complete the feedback survey. It should only take a minute.

Sia

Hi I am Sia , your intelligent chat assistant ! I can serve you with information related to following products.

Home Loan

Education Loan

Car Loan

Personal Loan

Recurring Deposit

(NB, gaps before punctuation and "to following" accurate transcription)

Mechanical Turk

left

Requesters have tasks they need to be completed

center

MTurk Marketplace

right

Workers want to earn money and work on interesting tasks

Endnotes

- Mark Christopher Marino, I, Chatbot: The Gender and Race Performativity of Conversational Agents, 2006, http://proquest.umi.com/pqdweb?did=1126774981&sid=4&Fmt=2&clientId=48051&RQT=309&VName=PQD. 8. ↩

- Joseph Weizenbaum, “ELIZA: A computer program for the study of natural language communication between man and machine,” Communications of the ACM 9, no. 1 (1966): 36–45. 36. ↩

- Weizenbaum, “ELIZA: A computer program for the study of natural language communication between man and machine.” 37. ↩

- Weizenbaum, “ELIZA: A computer program for the study of natural language communication between man and machine.” 37. ↩

- Weizenbaum, “ELIZA: A computer program for the study of natural language communication between man and machine.” 40. ↩

- Sherry Turkle, Life on the Screen: Identity in the Age of the Internet (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995). 101. ↩

- Joseph Weizenbaum, Computer Power and Human Reason: From Judgment to Calculation. (New York: W. H. Freeman and Company, 1976). 240. ↩

- V. Cerf, “PARRY Encounters the DOCTOR,” accessed June 12, 2019, https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc439. ↩

- More recently the ACM published NASA researcher and science fiction writer Geoffrey A. Landis’s intriguing short story “The Chatbot and the Drone.” It features the pair conversing to contemplate the ethics surrounding semiautonomous AI under the header “Autonomous or not, design is destiny.” Geoffrey A. Landis, “Future Tense: The Chatbot and the Drone,” accessed June 12, 2019, https://cacm.acm.org/magazines/2014/7/176207-future-tense-the-chatbot-and-the-drone/abstract. ↩

- Rollo Carpenter, “Jabberwacky – About Thoughts – An Artificial Intelligence AI Chatbot, Chatterbot or Chatterbox, Learning AI, Database, Dynamic – Models Way Humans Learn – Simulate Natural Human Chat – Interesting, Humorous, Entertaining,” April 5, 2005, https://web.archive.org/web/20050405201714/http:/jabberwacky.com/j2about. ↩

- Kevin Warwick and Huma Shah, “Can Machines Think? A Report on Turing Test Experiments at the Royal Society,” Journal of Experimental and Theoretical Artificial Intelligence 28, no. 6 (November 1, 2016): 989–1007, https://doi.org/10.1080/0952813X.2015.1055826. ↩

- Amir Shevat, Designing Bots: Creating Conversational Experiences (Sebastopol, CA: O’Reilly, 2017). ↩

- See Frances Dyson, Sounding New Media: Immersion and Embodiment in the Arts and Culture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009). for a discussion of REA (“Real Estate Agent”), a female embodied conversational assistant prototype developed by HCI researchers Timothy Bickmore and Justine Cassell, and its relationship to the 2008 housing crisis (pp. 73–77; 125–129). ↩

- See also T. Bickmore and J. Cassell, “Social Dialogue with Embodied Conversational Agents,” in Natural, Intelligent and Effective Interaction with Multimodal Dialogue Systems, ed. J. van Kuppevelt, L. Dybkjaer, and N. Bernsen (New York: Kluwer Academic, 2004). ↩

- Liliana Laranjo et al., “Conversational Agents in Healthcare: A Systematic Review,” Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 25, no. 9 (September 1, 2018): 1248–58, https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocy072. ↩

- See https://woebot.io/. ↩

- “Revision of the Priority Areas to Which Robot Technology Is to Be Introduced in Nursing Care,” Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, 2014, https://web.archive.org/web/20181112042446/https://www.meti.go.jp/english/press/2017/1012_002.html. ↩

- Sherry Turkle, Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other (New York: Basic Books, 2011). 6. ↩

- Eric Topol, “Preparing the Healthcare Workforce to Deliver the Digital Future: An Independent Report on Behalf of the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care,” Topol Review, February 2019. ↩

- For example: Rik Crutzen et al., “An Artificially Intelligent Chat Agent That Answers Adolescents’ Questions Related to Sex, Drugs, and Alcohol: An Exploratory Study,” Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine 48, no. 5 (May 2011): 514–19, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.09.002. ↩

- John Durham Peters, Speaking into the Air: A History of the Idea of Communication (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999). 234. ↩

- One of the most extensive summaries of the effects of gendered voices in machine interfaces is to be found in Clifford Nass and Scott Brave, Wired for Speech: How Voice Activates and Advances the Human-Computer Relationship (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2005). As the authors note, “this tendency for people, especially males, to take males more seriously than females extended to the obviously synthetic world of technology” and “Even Synthetic Voices Activate a Wide Range of Stereotypes” (pp. 15, 26). ↩

- See for example Friedrich A Kittler, Gramophone, Film, Typewriter, trans. Geoffrey Winthrop-Young and Michael Wutz (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1999). 183–198. ↩

- Also Leah Price and Pamela Thurschwell, eds., Literary Secretaries/Secretarial Culture (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2005). ↩

- Jennifer S Light, “When Computers Were Women,” Technology and Culture. 40 (1999). ↩

- David Alen Grier, When Computers Were Human (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2007). ↩

- Katherine Hayles, My Mother Was a Computer: Digital Subjects and Literary Texts (Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press, 2005). ↩

- But to women, word processing was often sold as a feminist innovation as, theoretically, female secretaries would be freed from subservient labor like taking dictation. ↩

- “The Reproduction of Labor Power in the Global Economy and the Unfinished Feminist Revolution (2008)” in Silvia Federici, Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction, and Feminist Struggle (Oakland, Calif.; Brooklyn, N.Y.; London: PM Press, Common Notions: Autonomedia, Turnaround, 2012). 91–111, 106–107. ↩

- HM Revenue & Customs, “HMRC Annual Report and Accounts: 2015 to 2016,” 2016, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/hmrc-annual-report-and-accounts-2015-to-2016. 48. ↩

- Alastair Sharp and Allison Martell, “Infidelity Website Ashley Madison Facing FTC Probe, CEO Apologizes,” Reuters, July 5, 2016, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-ashleymadison-cyber-idUSKCN0ZL09J. ↩

- Telegraph Reporters, “Ashley Madison Admits Tricking Men with Fake Fembots,” Telegraph, July 6, 2016, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/women/life/ashley-madison-admits-tricking-men-with-fake-fembots/. ↩

- Chloe Rose Stuart-Ulin, “You Could Be Flirting on Dating Apps with Paid Impersonators,” Quartz, accessed June 12, 2019, https://qz.com/1247382/online-dating-is-so-awful-that-people-are-paying-virtual-dating-assistants-to-impersonate-them/. ↩

- Sam Anthony, “Me, My Selfie and I with Ryan Gander” (BBC Four, March 18, 2019). ↩

- Sam Sabri, “Convince Microsoft to Keep Cortana as the Name for Your Future Digital Assistant | Windows Central,” accessed June 12, 2019, https://www.windowscentral.com/convince-microsoft-keep-cortana-name-your-future-digital-assistant. ↩

- Leah Fessler, “We Tested Bots Like Siri and Alexa to See Who Would Stand Up to Sexual Harassment,” Quartz, accessed June 12, 2019, https://qz.com/911681/we-tested-apples-siri-amazon-echos-alexa-microsofts-cortana-and-googles-google-home-to-see-which-personal-assistant-bots-stand-up-for-themselves-in-the-face-of-sexual-harassment/. ↩

- Fessler, “We Tested Bots Like Siri and Alexa to See Who Would Stand Up to Sexual Harassment.” ↩

- Jacqueline Feldman, “The Bot Politic,” New Yorker, December 31, 2016, https://www.newyorker.com/tech/annals-of-technology/the-bot-politic. ↩

- See also: Matt Simon, “It’s Time to Talk about Robot Gender Stereotypes,” Wired, October 3, 2018, https://www.wired.com/story/robot-gender-stereotypes/. ↩

- And Laura Sydell, “The Push For A Gender-Neutral Siri,” NPR.org, accessed June 12, 2019, https://www.npr.org/2018/07/09/627266501/the-push-for-a-gender-neutral-siri. ↩

- UNESCO et al., “I’d Blush If I Could: Closing Gender Divides in Digital Skills through Education” (Paris: UNESCO, 2019), https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000367416. 5. ↩

- See https://i-dat.org/women-reclaiming-ai-for-activism/; https://www.feministinternet.com/ and http://elviavasconcelos.com/Feminist-Alexa; and https://www.genderlessvoice.com/. ↩

- UNESCO et al., “I’d Blush If I Could: Closing Gender Divides in Digital Skills through Education.” 85. ↩

- UNESCO et al., “I’d Blush If I Could: Closing Gender Divides in Digital Skills through Education.” 88, 123. ↩

- UNESCO et al., “I’d Blush If I Could: Closing Gender Divides in Digital Skills through Education.” 112. ↩

- UNESCO et al., “I’d Blush If I Could: Closing Gender Divides in Digital Skills through Education.” 103. ↩

- Julie Wosk, My Fair Ladies: Female Robots, Androids and Other Artificial Eves (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2015). 5. ↩

- Wosk, My Fair Ladies. 27. ↩

- Weizenbaum, “ELIZA: A computer program for the study of natural language communication between man and machine.” 36. ↩

- Wosk, My Fair Ladies. 7. ↩

- Donna Haraway, “A Manifesto for Cyborgs: Science, Technology, and Socialist Feminism in the 1980s,” Australian Feminist Studies 2, no. 4 (March 1, 1987): 1–42, https://doi.org/10.1080/08164649.1987.9961538. ↩

- Michael Adas, Machines as the Measure of Men: Science, Technology, and Ideologies of Western Dominance (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2015). ↩

- See particularly James W. Cortada, The Digital Flood: The Diffusion of Information Technology Across the U.S., Europe, and Asia (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012). ↩

- David Morley and Kevin Robins, “Techno-Orientalism: Japan Panic,” in Spaces of Identity: Global Media, Electronic Landscapes and Cultural Boundaries (London: Routledge, 1995), 147–73. 149. ↩

- Morley and Robins, “Techno-Orientalism.” 172. ↩

- See, for example, the work of Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, Lisa Nakamura, Toshiyo Ueno, and David S. Roh, Betsy Huang, and Greta A. Niu, Techno-Orientalism: Imagining Asia in Speculative Fiction, History, and Media (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2015). ↩

- R. John Williams, The Buddha in the Machine: Art, Technology, and the Meeting of East and West (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2014). 1. ↩

- Williams, The Buddha in the Machine. 6. ↩

- Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, Control and Freedom Power and Paranoia in the Age of Fiber Optics. (Cambridge, Mass.; London: MIT Press, 2008). 177. ↩

- Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, “Race and/as Technology, or How to Do Things to Race,” in Race after the Internet, ed. Lisa Nakamura and Peter Chow-White (New York: Routledge, 2012). 38. ↩

- Chun, “Race and/as Technology.” 38. ↩

- Chun, “Race and/as Technology.” 38. ↩

- Chun, “Race and/as Technology.” 51. Compare Luc Besson’s film Lucy (2014), which contrasts an anthropological African past – the hero’s namesake is an Australopithecus afarensis skeleton discovered in Ethiopia in 1975 – with a Far Eastern technological present. ↩

- Chun also puts forward the provocation, “Can the abject, the Orientalized, the robot-like data-like Asian/Asian American other be a place from which something like insubordination or creativity can arise?” Chun, “Race and/as Technology.” 51. ↩

- Tavia Nyong’o, Afro-Fabulations: The Queer Drama of Black Life (New York: New York University Press, 2019). 185. ↩

- Nyong’o, Afro-Fabulations. 189. ↩

- Nyong’o, Afro-Fabulations. 192, 197–198. ↩

- Mark C Marino, “The Racial Formation of Chatbots,” CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 16, no. 5 (2014). 1. ↩

- “Ask A.N.A.C.A.O.N.A. (the Robots) Anything,” February 9, 2005, https://web.archive.org/web/20050209012849/http:/www.centrelink.org/anacaonarobots.htm. ↩

- Maximilian Forte, “‘Asking Anacaona Anything,’” CAC Review 3, no. 9 (October 2002), https://web.archive.org/web/20050214081436/http:/www.centrelink.org/Oct2002.html#anacaona. ↩

- Marino, “The Racial Formation of Chatbots.” 5. ↩

- Lisa Nakamura, Cybertypes: Race, Ethnicity, and Identity on the Internet (New York: Routledge, 2002). 42. ↩

- See http://www.square-bear.co.uk/mitsuku/home.htm. ↩

- Chun, Control and Freedom Power and Paranoia in the Age of Fiber Optics. 242. ↩

- Silvia Federici, “Reproduction and Feminist Struggle in the New International Division of Labor (1999)” in Federici, Revolution at Point Zero. 65–75, p. 71. ↩

- Marino, “The Racial Formation of Chatbots.” 5. ↩

- Elle Hunt, “Tay, Microsoft’s AI Chatbot, Gets a Crash Course in Racism from Twitter,” The Guardian, March 24, 2016, sec. Technology, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/mar/24/tay-microsofts-ai-chatbot-gets-a-crash-course-in-racism-from-twitter. ↩

- Ayhan Aytes, “Return of the Crowds: Mechanical Turk and Neoliberal States of Exception,” in Digital Labor: The Internet as Playground and Factory, ed. Trebor Scholz (New York; London: Routledge, 2012), 150–86. 162. ↩

- Another notable example is the Chinese conglomerate Alibaba, named because it “brings to mind ‘open sesame,’ representing that our platforms open a doorway to fortune for small businesses,” according to the website. “‘Why Is the Company Called “Alibaba”?,’” FAQs (blog), 2019, www.alibabagroup.com/en/about/faqs. ↩

- “Amazon Mechanical Turk,” accessed June 12, 2019, https://www.mturk.com/. ↩

- Paul Hitlin and Pew Research Center, Research in the Crowdsourcing Age, a Case Study: How Scholars, Companies and Workers Are Using Mechanical Turk, a “Gig Economy” Platform, for Tasks Computers Can’t Handle, 2016, http://www.pewinternet.org/files/2016/07/PI_2016.07.11_Mechanical-Turk_FINAL.pdf. ↩

- Miranda Katz, “Amazon Mechanical Turk Workers Have Had Enough,” WIRED, August 23, 2017, https://www.wired.com/story/amazons-turker-crowd-has-had-enough/. ↩

- Mark Harris, “Amazon’s Mechanical Turk Workers Protest: ‘I Am a Human Being, Not an Algorithm,’” The Guardian, December 3, 2014, sec. Technology, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2014/dec/03/amazon-mechanical-turk-workers-protest-jeff-bezos. ↩

- Hitlin and Pew Research Center, Research in the Crowdsourcing Age, a Case Study. ↩

- “FAQs: About Mechanical Turk” at https://www.mturk.com/help. Accessed June 12, 2019. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Jason Pontin, “Artificial Intelligence, with Help from the Humans,” New York Times, March 25, 2007, sec. Business Day, https://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/25/business/yourmoney/25Stream.html. ↩

- Jaron Lanier, Who Owns the Future? (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2014). 177. ↩

- See, for example Gunalan Nadarajan, “Islamic Automation: A Reading of al-Jazari’s The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices (1206),” in MediaArtHistories, ed. Oliver Grau (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2007), 163–78. ↩

- John R. Searle, “Minds, Brains, and Programs,” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 3, no. 3 (September 1980): 417–24, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X00005756. 417–418. ↩

- See Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, Control and Freedom Power and Paranoia in the Age of Fiber Optics. (Cambridge, Mass.; London: MIT Press, 2008). 205, n. 79. ↩

- Searle, “Minds, Brains, and Programs.” 419. ↩

- William G. Lycan, “The Functionalist Reply (Ohio State),” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 3, no. 3 (September 1980): 434–35, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X00005860. 435. ↩

- Retallack, Joan. “The Woman in the Chinese Room... A Prospective," Iowa Review 26, no. 2 (Summer, 1996): 159–62. 160. ↩

Bibliography

- Adas, Michael. Machines as the Measure of Men: Science, Technology, and Ideologies of Western Dominance. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2015.

- Anthony, Sam. “Me, My Selfie and I with Ryan Gander.” BBC Four, March 18, 2019.

- Aytes, Ayhan. “Return of the Crowds: Mechanical Turk and Neoliberal States of Exception.” In Digital Labor: The Internet as Playground and Factory, edited by Trebor Scholz, 150–86. New York; London: Routledge, 2012.

- Bickmore, T., and J. Cassell. “Social Dialogue with Embodied Conversational Agents.” In Natural, Intelligent and Effective Interaction with Multimodal Dialogue Systems, edited by J. van Kuppevelt, L. Dybkjaer, and N. Bernsen. New York: Kluwer Academic, 2004.

- Carpenter, Rollo. “Jabberwacky – About Thoughts – An Artificial Intelligence AI Chatbot, Chatterbot or Chatterbox, Learning AI, Database, Dynamic – Models Way Humans Learn – Simulate Natural Human Chat – Interesting, Humorous, Entertaining,” April 5, 2005. https://web.archive.org/web/20050405201714/http:/jabberwacky.com/j2about.

- Cerf, V. “PARRY Encounters the DOCTOR.” Accessed June 12, 2019. https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc439.

- Chun, Wendy Hui Kyong. “Race and/as Technology, or How to Do Things to Race.” In Race after the Internet, edited by Lisa Nakamura and Peter Chow-White. New York: Routledge, 2012.

- Chun, Wendy Hui Kyong. Control and Freedom Power and Paranoia in the Age of Fiber Optics. Cambridge, Mass.; London: MIT Press, 2008.

- Cortada, James W. The Digital Flood: The Diffusion of Information Technology Across the U.S., Europe, and Asia. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Crutzen, Rik, Gjalt-Jorn Y. Peters, Sarah Dias Portugal, Erwin M. Fisser, and Jorne J. Grolleman. “An Artificially Intelligent Chat Agent That Answers Adolescents’ Questions Related to Sex, Drugs, and Alcohol: An Exploratory Study.” Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine 48, no. 5 (May 2011): 514–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.09.002.

- Dyson, Frances. Sounding New Media: Immersion and Embodiment in the Arts and Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009.

- Federici, Silvia. Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction, and Feminist Struggle. Oakland, Calif.; Brooklyn, N.Y.; London: PM Press, Common Notions: Autonomedia, Turnaround, 2012.

- Feldman, Jacqueline. “The Bot Politic.” New Yorker, December 31, 2016. https://www.newyorker.com/tech/annals-of-technology/the-bot-politic.

- Fessler, Leah. “We Tested Bots Like Siri and Alexa to See Who Would Stand Up to Sexual Harassment.” Quartz. Accessed June 12, 2019. https://qz.com/911681/we-tested-apples-siri-amazon-echos-alexa-microsofts-cortana-and-googles-google-home-to-see-which-personal-assistant-bots-stand-up-for-themselves-in-the-face-of-sexual-harassment/.

- Forte, Maximilian. “‘Asking Anacaona Anything.’” CAC Review 3, no. 9 (October 2002). https://web.archive.org/web/20050214081436/http:/www.centrelink.org/Oct2002.html#anacaona.

- Grier, David Alen. When Computers Were Human. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2007.

- Haraway, Donna. “A Manifesto for Cyborgs: Science, Technology, and Socialist Feminism in the 1980s.” Australian Feminist Studies 2, no. 4 (March 1, 1987): 1–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/08164649.1987.9961538.

- Harris, Mark. “Amazon’s Mechanical Turk Workers Protest: ‘I Am a Human Being, Not an Algorithm.’” The Guardian, December 3, 2014, sec. Technology. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2014/dec/03/amazon-mechanical-turk-workers-protest-jeff-bezos.

- Hayles, Katherine. My Mother Was a Computer: Digital Subjects and Literary Texts. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

- Hitlin, Paul, and Pew Research Center. Research in the Crowdsourcing Age, a Case Study: How Scholars, Companies and Workers Are Using Mechanical Turk, a “Gig Economy” Platform, for Tasks Computers Can’t Handle, 2016. http://www.pewinternet.org/files/2016/07/PI_2016.07.11_Mechanical-Turk_FINAL.pdf.

- HM Revenue & Customs. “HMRC Annual Report and Accounts: 2015 to 2016,” 2016. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/hmrc-annual-report-and-accounts-2015-to-2016.

- Hunt, Elle. “Tay, Microsoft’s AI Chatbot, Gets a Crash Course in Racism from Twitter.” The Guardian, March 24, 2016, sec. Technology. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/mar/24/tay-microsofts-ai-chatbot-gets-a-crash-course-in-racism-from-twitter.

- Katz, Miranda. “Amazon Mechanical Turk Workers Have Had Enough.” WIRED, August 23, 2017. https://www.wired.com/story/amazons-turker-crowd-has-had-enough/.

- Kittler, Friedrich A. Gramophone, Film, Typewriter. Translated by Geoffrey Winthrop-Young and Michael Wutz. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1999.

- Landis, Geoffrey A. “Future Tense: The Chatbot and the Drone.” Accessed June 12, 2019. https://cacm.acm.org/magazines/2014/7/176207-future-tense-the-chatbot-and-the-drone/abstract.

- Lanier, Jaron. Who Owns the Future? New York: Simon and Schuster, 2014.

- Laranjo, Liliana, Adam G. Dunn, Huong Ly Tong, Ahmet Baki Kocaballi, Jessica Chen, Rabia Bashir, Didi Surian, et al. “Conversational Agents in Healthcare: A Systematic Review.” Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 25, no. 9 (September 1, 2018): 1248–58. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocy072.

- Leah Price, and Pamela Thurschwell, eds. Literary Secretaries/Secretarial Culture. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2005.

- Light, Jennifer S. “When Computers Were Women.” Technology and Culture. 40 (1999).

- Lycan, William G. “The Functionalist Reply (Ohio State).” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 3, no. 3 (September 1980): 434–35. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X00005860.

- Marino, Mark Christopher. I, Chatbot: The Gender and Race Performativity of Conversational Agents, 2006. http://proquest.umi.com/pqdweb?did=1126774981&sid=4&Fmt=2&clientId=48051&RQT=309&VName=PQD.

- Marino, Mark C. “The Racial Formation of Chatbots.” CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 16, no. 5 (2014).

- Morley, David, and Kevin Robins. “Techno-Orientalism: Japan Panic.” In Spaces of Identity: Global Media, Electronic Landscapes and Cultural Boundaries, 147–73. London: Routledge, 1995.

- Nadarajan, Gunalan. “Islamic Automation: A Reading of al-Jazari’s The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices (1206).” In MediaArtHistories, edited by Oliver Grau, 163–78. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2007.

- Nakamura, Lisa. Cybertypes: Race, Ethnicity, and Identity on the Internet. New York: Routledge, 2002.

- Nass, Clifford, and Scott Brave. Wired for Speech: How Voice Activates and Advances the Human-Computer Relationship. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2005.

- Nyong’o, Tavia. Afro-Fabulations: The Queer Drama of Black Life. New York: New York University Press, 2019.

- Peters, John Durham. Speaking into the Air: A History of the Idea of Communication. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999.

- Pontin, Jason. “Artificial Intelligence, with Help from the Humans.” New York Times, March 25, 2007, sec. Business Day. https://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/25/business/yourmoney/25Stream.html.

- Roh, David S., Betsy Huang, and Greta A. Niu. Techno-Orientalism: Imagining Asia in Speculative Fiction, History, and Media. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2015.

- Sabri, Sam. “Convince Microsoft to Keep Cortana as the Name for Your Future Digital Assistant | Windows Central.” Accessed June 12, 2019. https://www.windowscentral.com/convince-microsoft-keep-cortana-name-your-future-digital-assistant.

- Searle, John R. “Minds, Brains, and Programs.” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 3, no. 3 (September 1980): 417–24. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X00005756.

- Sharp, Alastair, and Allison Martell. “Infidelity Website Ashley Madison Facing FTC Probe, CEO Apologizes.” Reuters, July 5, 2016. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-ashleymadison-cyber-idUSKCN0ZL09J.

- Shevat, Amir. Designing Bots: Creating Conversational Experiences. Sebastopol, CA: O’Reilly, 2017.

- Simon, Matt. “It’s Time to Talk about Robot Gender Stereotypes.” Wired, October 3, 2018. https://www.wired.com/story/robot-gender-stereotypes/.

- “Amazon Mechanical Turk.” Accessed June 12, 2019. https://www.mturk.com/.

- Stuart-Ulin, Chloe Rose. “You Could Be Flirting on Dating Apps with Paid Impersonators.” Quartz. Accessed June 12, 2019. https://qz.com/1247382/online-dating-is-so-awful-that-people-are-paying-virtual-dating-assistants-to-impersonate-them/.

- Sydell, Laura. “The Push For A Gender-Neutral Siri.” NPR.org. Accessed June 12, 2019. https://www.npr.org/2018/07/09/627266501/the-push-for-a-gender-neutral-siri.

- Telegraph Reporters. “Ashley Madison Admits Tricking Men with Fake Fembots.” Telegraph, July 6, 2016. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/women/life/ashley-madison-admits-tricking-men-with-fake-fembots/.

- Topol, Eric. “Preparing the Healthcare Workforce to Deliver the Digital Future: An Independent Report on Behalf of the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care.” Topol Review, February 2019.

- Turkle, Sherry. Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other. New York: Basic Books, 2011.

- Turkle, Sherry. Life on the Screen: Identity in the Age of the Internet. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995.

- UNESCO, EQUALS Skills Coalition, Mark West, Rebecca Kraut, and Han Ei Chew. “I’d Blush If I Could: Closing Gender Divides in Digital Skills through Education.” Paris: UNESCO, 2019. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000367416.

- Warwick, Kevin, and Huma Shah. “Can Machines Think? A Report on Turing Test Experiments at the Royal Society.” Journal of Experimental and Theoretical Artificial Intelligence 28, no. 6 (November 1, 2016): 989–1007. https://doi.org/10.1080/0952813X.2015.1055826.

- Weizenbaum, Joseph. “ELIZA: A computer program for the study of natural language communication between man and machine.” Communications of the ACM 9, no. 1 (1966): 36–45.

- Weizenbaum, Joseph. Computer Power and Human Reason: From Judgment to Calculation. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company, 1976.

- Williams, R. John. The Buddha in the Machine: Art, Technology, and the Meeting of East and West. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2014.

- Wosk, Julie. My Fair Ladies: Female Robots, Androids and Other Artificial Eves. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2015.

- “Ask A.N.A.C.A.O.N.A. (the Robots) Anything,” February 9, 2005. https://web.archive.org/web/20050209012849/http:/www.centrelink.org/anacaonarobots.htm.

- FAQs. “‘Why Is the Company Called “Alibaba”?,’” 2019. www.alibabagroup.com/en/about/faqs.

- Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. “Revision of the Priority Areas to Which Robot Technology Is to Be Introduced in Nursing Care,” 2014. https://web.archive.org/web/20181112042446/https://www.meti.go.jp/english/press/2017/1012_002.html.