The Social Media Curation of Stories: Stories as a Feature on Snapchat and Instagram

The starting point for this research was the media companies’ design of stories as distinct features in their apps which happened in the course of my Life-Writing of the Moment Project. I felt that this story-designing spree needed to be interrogated especially given that, in the words of Instagram CEO Kevin Systrom, it involves drawing on “a format, and how you take it to a network and put your own spin on it.”1 As a design phase, producing stories as a distinct feature followed on from showing the moment. As I show, on the one hand, it has built on and further consolidated visual facilities and on the other, it seems to have co-opted the backlash of the narcissism and inauthenticity attached to the highly polished photos and selfies and to allow for “imperfect sharing.”

Many apps currently converge on launching story facilities as a way of allowing users to create a more continuous sharing of their everyday moments, to share “not just one moment, but all moments of their day.” This includes WhatsApp Status (2016), Twitter Moments (2016), and Facebook Stories (2017). I have focused on the hugely popular Snapchat Stories (2014) and Instagram Stories (2016). The feature of Stories has been described as “a game changer” for Snapchat,’2 and so it was no accident that it was largely replicated by Instagram Stories. As of 2017, the number of stories posted on Instagram surpassed that of Snapchat Stories: currently, more than 500 million accounts use Instagram Stories everyday.3 Teenagers who were the initial target audience and early adopters, post on average four times more stories a day than any other age group. This story-designing spree needs to be placed genealogically in the context of attempts by Facebook to go beyond the single feed and the present moment by allowing users to share memories. The Timeline is such an early attempt followed by the video “A Look Back,” which was launched for the tenth anniversary of the platform in 2014, and “On this day,” introduced in 2015, encouraging users to revisit posts and share them as memories. The curation of memories can be viewed as an antecedent to the curation of stories: what brings them together is the apps’ move to providing facilities that enable users to go beyond the single feed and the present moment. This is presented as a key feature in Snapchat and Instagram Stories. Stories are presented by apps as a novelty and an important step toward facilitating the so called rich and meaningful user content. But, as my analysis has shown, they ultimately build upon and consolidate the two design phases that I have put forward as pivotal for the engineering of storytelling communication on social media, that of sharing the moment as breaking news and of showing the moment.

Stories are essentially collections of snaps/photos (ten seconds max. on Snapchat and seven-seconds snaps) and/or video (fifteen seconds on Instagram), and increasingly live streaming too. As a distinct feature, stories acquire sociotechnical, iconic, and, importantly, embodied, action-button dimensions. Specifically, users perform habitual actions to both post and engage with stories. They click on their story button to share their story of the day.4 They used to swipe left on the main camera screen to access their friends’ stories on Snapchat. Now they swipe right. They can tap on a user’s profile to see their story, and a user’s profile picture on Instagram has a colorful ring around it to indicate that they have posted a story (see A Beginner’s Guide to Instagram Stories5). They use their smartphone for posting and viewing stories, and their viewing experience of Instagram Stories is much more immersive than anything else on the app, as they can view them full-screen. Users can also swipe right or left to skip between people’s stories. Increasingly, viewers of stories (e.g., followers on Instagram) can engage with stories more, for example, by replying, leaving comments, etc.

Initially, stories disappeared after twenty-four hours from posting, but now there are archiving and highlighting possibilities for stories that users want to save. Evolving affordances in stories direct users to post more, to make their stories more of a feature, to provide prompts for engagement, for example by mentioning and tagging friends and followers, and to link their stories with other content. In this way, they afford cross-syndication and increased data flow, for instance, by allowing posters to link their stories with other content, to use hashtags and location stickers. A case in point is the Paperclip icon on Snapchat which lets everyone, from ordinary users to advertisers, attach an external web link to their Snaps for their stories. Stories with such content-linking features can be included in the Search and Explore page of Instagram: this is done in the name of a story’s discoverability by other users, but it is also fair to assume that all such connecting facilities are conducive to advertising, often encouraging ordinary users to go to the websites of brands to check out products. It is also notable that as the facilities for stories are evolving, so is the quantification and trackability of content. For instance, if a story gets featured in a hashtag or location story by Instagram, the number of viewers who viewed it through the Instagram Explore page can be tracked.

We therefore see an increasing sophistication and complexity in what can be trackable by the platforms themselves and by users. It is notable that different types of users have differentiated access to tracking facilities: for instance, you can see your own story analytics using Instagram tools (e.g., Insights6) if you have a business account and over 10,000 followers. Users can track not just how many views their story has had but also the total number of story completions. On Snapchat, this refers to the number of users who may have opened up the first frame of a Snapchat story but then abandoned it and, on Instagram, those who skipped (to go to the next account’s story) a story or exited it (left the story to return to their feed). In addition, users can track how many taps a sticker they have placed in their Instagram story has had. (Stickers include geolocations, hashtags, and mentions). Another important analytic and engagement gauging tool on Instagram is the distinction between impressions (the total number of views a story has received) and reach (the number of unique accounts who saw a story). Overall, the constant provision of increasingly sophisticated metrics for stories alongside tools to users for accessing them are arguably the biggest identifiable aspect of the ongoing evolution and updates of the design of stories. At the time of writing this, some of the newest metrics include Directions, Calls, Texts, and Emails: these track and measure the effect that Instagram Stories have on the action performed on a user’s profile call to action (CTA) buttons. Metrics thus prove to be not just multifaceted and complex but also deeply interwoven into the stories’ design.7

Overall, stories on apps as designed features are reminiscent of Turkle’s definition of “evocative objects” which she employed to refer to smartphones.8 In a similar vein, stories as a designed feature become repositories of the user’s everyday lives; they evoke emotions, memories, social relationships. Their placement on an app, the embodied ways in which we habitually interact with them, our investment in attention and affect when posting and engaging with them, become deeply embedded into our daily lives’ practices. Put differently, they become part of what Kitchin and Dodge term code/space to denote the ways in which software and devices are configuring concepts of space and identity for the users, shaping and even delimiting for them what they can do.9

Platform and cultural media studies scholars have begun to interrogate how social media with their algorithms are essentially directional to specific modes of sociality, users’ self-presentation, and relations with others.10,11,12,13 By directional, they mean that they prompt, encourage, engender, and provide users with specific tools for specific ways of (inter)acting on social media. Bucher talks about the programmed sociality of Facebook in the ways in which it prescribes norms and values about friendship. This amongst others involves “simulating and augmenting the notion of shared history, prompting users to take certain relational actions but also continuously measuring, valuing, and examining these actions according to some underlying criteria or logic.”14 Elsewhere, Bucher has shown that not taking up these metricized prompts for specific ways of being a Friend on Facebook comes with a cost to users’ popularity.15 She has claimed that being popular both hinges on participating in prescribed ways and in turn generates more participation and popularity. This raises the “threat of invisibility” for users who do not conform with the engineered, sociotechnical arrangements of Facebook that emphasize sharing and participation. Stories as a distinct feature on apps genealogically build on such previous engineering attempts of apps, in particular Facebook, to metricize popularity, and they therefore need to be viewed as an evolved form of programmed sociality.

There is increasing recognition that any critical analysis of communication on social media needs to incorporate a “values in design” perspective.16 How apps design their space, what affordances they offer their users, what participation means for them, are not ideologically free choices, but instead they encapsulate values, norms, and beliefs of a whole network of actors, ranging from programmers to designers, product managers and beta users.17Although this is by no means a deterministic relationship and users should not be viewed as passive dupes, the potential of the apps engineering for specific communication practices to become normalized, widely available, and highly sought after by users in the game of ensuring popularity should not be underestimated. This is especially so given the media affordances of amplification and scaleability that can easily augment and sediment specific communication choices.

With the above in mind, my contention has been that narrative discourse analysis needs to urgently turn its critical attention to story features on social media. What definitions and views of stories underpin such story features on apps? What facilities are on offer for posting stories, how are they being branded, and why?18 Who is positioned as an ideal story creator and audience of those stories and why? The corpus-assisted analysis of how Stories are launched by Snapchat and Instagram and subsequently discussed and reviewed in online media has made apparent a notable convergence on how stories are conceptualized and what kinds of affordances are offered for them.19,20 In particular, the explicit designing of Stories as an accumulation of moments was found to come with certain paradoxes and mismatches between the rhetoric of the design and the affordances on offer.

These mismatches are revealing of a redesignation of key ingredients of stories, in particular time, creativity and audience engagement. This, in turn, suits the apps’ agenda of metricization of users’ lives and their ever closer links with advertising. Links with advertising are attestable in the language of business and marketing that is incorporated in the design of story features which render stories as commoditized, consumable, and branded activities. Sharing-lives-in-the-moment, I argue, is being designed, promoted, and monetized with the millennials and Generation Z as a primary target audience of early adopter users.21 This has implications for the kinds of lives and subjectivities Stories have the potential to make widely available.

In line with platform studies, I view platforms as ideologically laden spaces and socio-material actors with influence on communication.22,23,24 I also draw on the emerging critical discourse-analytic work on the significance of the apps’ discourses, especially via their CEOs and product managers, for how users are discursively constructed and what roles are projected for them. 25 To explore such discourses on stories, I employ corpus-assisted discourse studies (CADS) principles and techniques so as to uncover hidden meanings and interconnections in the offerings of apps for stories. In tune with a critical discourse analytic agenda, I view such opaque meanings as having the potential to promote certain stories and semiotic choices in them, making them more available than others and even normalizing them.

To complement the microanalysis of my data sets (see Sharing the Moment as Breaking News and Showing the Moment), I draw on corpus-assisted discourse studies for the analysis of published surveys, platform blogs, including any publicity about new features for stories, and reviews of such new features in online tech magazines.26 I view this material as a sort of paratext, an important part of the complex mediation between algorithms, affordances, discourses of media companies, and users’ practices.27 A corpus-assisted analysis allows me to undertake a critical approach to social media affordances in connection with the microanalysis of users’ stories and the ethnographic tracking of changes in media affordances.28 Specifically, the corpus methodology is instrumental in identifying discourses of how stories are being viewed and defined and how they connect with the breaking news logic (see Sharing the Moment as Breaking News). In CADS, the analysis tends to follow a recursive process of shifting between quantitative handlings of large data and “funnelling down” from identified patterns to microanalyses of stretches of data with consideration of context.29,30,31

Bringing in corpus methods to complement microanalytical and digital ethnographic methods works well with the principle of working with what Markham calls remix methods.32 These are playful, imaginative, open-minded, and synergetic methods, in the spirit of social media engagements themselves. Markham finds such remixing of methods well-suited to the exploration of online communication. Closely related to this is the methodological principle of bracketing.33 This allows analysts to prioritize different questions, for example, the what, why, and how, at different stages in one’s research and to shift in methods depending on what suits the current priorities of a research.

Remixing and bracketing afford a critical approach to affordances for stories on social media apps. Corpus methods are synergized in this project with other tracking methods. They help uncover hidden meanings and interconnections in the discourse of apps and their offerings for stories. They are instrumental in identifying the “values in design,” the discourses of how stories are being viewed and defined by the apps as part of designing them. Such values are normally not spelled out: they are instead opaque meanings that have the potential to promote certain stories and semiotic choices in them, making them more available than others and even normalizing them.

In CADS, it is widely accepted that shifting between quantitative handlings of large data and “funnelling down” from identified patterns to microanalyses of stretches of data with consideration of context are recursive processes.34,35 In our case, this relationship is reversed, but the processes are still recursive. In other words, I started from microanalytic observations which I wanted to scale up with larger data sets. But I also funnel down on the basis of corpus analysis insights to further microanalysis of selected processes. The fact that qualitative, multimodal analysis of online media posts about stories had been carried out prior to the corpus compilation and that a parallel, sampled analysis of whole articles took place mitigated the context impoverishment involved in a corpus compilation when multimodal data are involved.

The corpus-assisted analysis of the present study followed on from a qualitative analysis of key articles on Stories as a feature on Instagram and Snapchat. Using previous findings on how users adapt media facilities for sharing the moment to produce small stories, I sought to identify the extent to which Stories as a feature build on or, indeed, depart from established practices. In particular, I focused on how aspects of plot in the Stories were talked about and what facilities were offered for them. This included what connections were made between Stories and time, what was proposed as a tellable story and how, and what modes of audience engagement were promoted. I noted the significance of the lexis moments in how Stories were connected with time, a constant referencing to telling stories when in fact Stories were primarily defined as collections of snaps and photographs, and the abundance of metricization and tools in the creation of Stories. In parallel, my ethnographic tracking of a group of female teenagers whose selfies I had analyzed (see Showing the Moment) suggested their move to Snapchat and then Instagram Stories as a more “authentic” way of presenting themselves and their lives than selfies. This tallied with celebrities and influencers adopting Stories as a way of presenting nonfiltered, nonnarcissistic selves.

In compiling a web-based corpus on how Stories as an app feature are launched and reviewed, my aim was to scale up and probe into the above observations with a view to documenting their resonance beyond individual texts and cases and to uncovering any lexical and thematic associations that revealed hidden meanings in the design and promotion of Stories. The results of the corpus analysis, in turn, guided further microanalysis. For example, how influencers put those stories affordances to use and how they respond to them seem like natural next steps to take as part of exploring the dialectic between algorithmic design and users’ communicative practices.

The corpus was compiled with the expert help of Anda Drasovean.36

Using advanced Google search facilities on Stories, Instagram, Snapchat, and Facebook, and the search engines Google, Bing, and DuckDuckGo,37 we pulled approximately 1,213 articles (excluding duplicates) related to the introduction and review of Snapchat Stories (2014) and Instagram Stories (2016).38 The obtained corpus (henceforth the EgoMedia corpus) contains 156 files and approx. 1,000,000 words.

The main types of sources include:

- online newspapers (Mail Online, USA Today, New York Times, Independent, BBC, Metro)39;

- tech magazines and blogs (TechJunkie, The Verge, Macworld, The Next Web, TechCrunch, Wired)40;

- business/online marketing magazines and blogs (Sprout Social, Marketing Land, Forbes, Business Insider, searchenginejournal.com)41;

- digital media magazines and blogs (BuzzFeed, Hootsuite)42;

- Instagram/Snapchat blogs43;

- lifestyle blogs and online magazines (People Magazine, Romper)44.

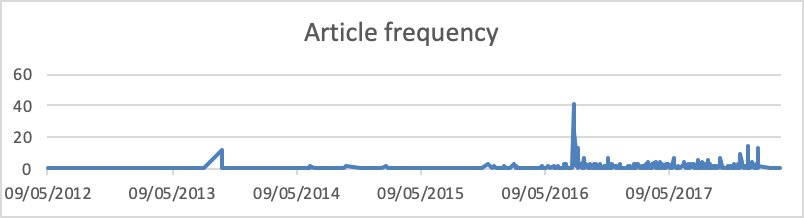

The articles were collected over a period of two weeks in January 2018, and the publication dates include the time interval May 9, 2012–January 30, 2018. The graph below shows the distribution of the articles over time. The spikes in the graph represent key events in the evolution of Stories (e.g., August 2, 2016 – Instagram launches Stories).

Our search results (URL) were retrieved using a browser add-on (Linkclump) and saved in a spreadsheet. The unique URLs resulting from the searches were fed into a custom-made Python script. Using the Python module “Newspapers,” this script downloads the .html file for each URL, and then parses it to extract the page’s/article’s title, date of publication, author, text, and any images and accompanying videos.45 Once all this information was downloaded and parsed, it was saved in a CSV file. The last step in the corpus-building process was that of encoding the text and metadata in an XML format so that they can be read and searched with the help of corpus analysis software (e.g., Sketch Engine). We subsequently generated two keyword lists, one containing single-word, the other multiword units, using the reference corpus EnTenTen15 (or English Web 2015), a web corpus of approximately 15 billion words, collected in 2015. We also used the British National Corpus (BNC) and the TED_en Corpus (transcriptions of TED talks), both of which are available on Sketch Engine, to generate and compare word sketches: these are lists of salient collocates grouped by grammatical category.

Following funneling down principles of CADS, we identified keywords and key semantic domains, collocates, so as to explore the textual behavior of keywords, and concordances, so as to explore patterns of lexical associations. The manual analysis of the highest ranked 100 keywords and key phrases (by comparison to our reference corpora) identified time (especially moments), sharing, pronouns, business, creativity, and visuality in the top 50 categories of words.

| Rank | Keyword | Score | Frequency (raw) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 111.39 | 12,236 | |

| 2 | Snapchat | 95.58 | 9,941 |

| 3 | Stories | 75.12 | 8,500 |

| 4 | Story | 20.65 | 2,456 |

| 5 | stories | 16.73 | 3,316 |

| 6 | app | 14.39 | 2,331 |

| 7 | users | 14.24 | 3,281 |

| 8 | feature | 13.66 | 2,487 |

| 9 | story | 13.26 | 3,832 |

| 10 | 13.23 | 2,102 | |

| 11 | followers | 13.22 | 1,441 |

| 12 | videos | 11.91 | 1,804 |

| 13 | content | 11.15 | 2,811 |

| 14 | photos | 10.61 | 1,677 |

| 15 | tap | 10.29 | 1,091 |

| 16 | Snap | 9.81 | 926 |

| 17 | snaps | 8.5 | 792 |

| 18 | brands | 8.36 | 963 |

| 19 | photo | 8.32 | 1,288 |

| 20 | video | 8.11 | 2,345 |

| 21 | your | 8.08 | 15,150 |

| 22 | filters | 7.76 | 781 |

| 23 | profile | 7.68 | 1,009 |

| 24 | feed | 7.58 | 966 |

| 25 | add | 7.43 | 1,457 |

| 26 | audience | 7.35 | 1,178 |

| 27 | screen | 7.32 | 1,165 |

| 28 | post | 7.29 | 1,686 |

| 29 | brand | 7.05 | 1,072 |

| 30 | snap | 7.03 | 663 |

| 31 | icon | 6.89 | 713 |

| 32 | share | 6.73 | 1,899 |

| 33 | platform | 6.49 | 1,104 |

| 34 | Snaps | 6.35 | 556 |

| 35 | moments | 6.29 | 727 |

| 36 | posts | 6.23 | 782 |

| 37 | 6.04 | 771 | |

| 38 | swipe | 5.68 | 495 |

| 39 | camera | 5.66 | 780 |

| 40 | friends | 5.42 | 1,319 |

| 41 | you | 5.23 | 17,838 |

| 42 | disappear | 5.06 | 460 |

| 43 | stickers | 4.96 | 430 |

| 44 | media | 4.92 | 1,551 |

| 45 | Memories | 4.65 | 390 |

| 46 | You | 4.64 | 2,786 |

| 47 | button | 4.58 | 548 |

| 48 | Your | 4.55 | 960 |

| 49 | social | 4.55 | 2,053 |

| 50 | Tap | 4.51 | 376 |

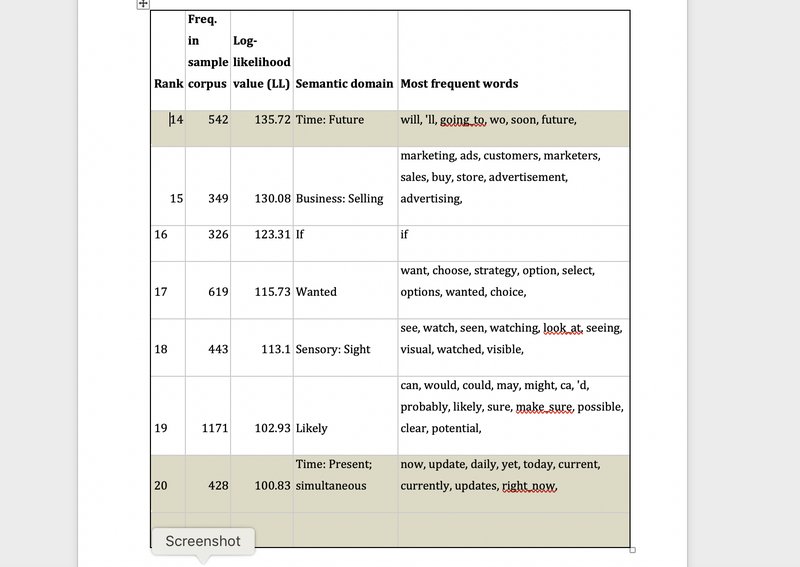

A key semantic domain analysis was also carried out, using the program Wmatrix and a sample of 100 randomly picked articles.46

| Rank | Freq. in sample corpus | Log-likelihood value (LL) | Semantic domain | Most frequent words |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2150 | 2173.72 | Speech: Communicative | stories, story, content, said, say, comments, says, told, talking, conversation, talk, point, comment, saying, spoke, note, mentioned, |

| 2 | 701 | 996.04 | Using | users, use, using, user, used, uses, function, |

| 3 | 654 | 785.25 | Arts and crafts | photos, photo, camera, icon, pictures, picture, design, draw, drawings, drawing, |

| 4 | 3403 | 783.41 | Unmatched | Instagram, snapchat, app, apps, whatsapp, slideshow, screenshot, Canva, Stacy, emoji, geofilter, iphone, Ingrid, username, millennials, Shopify, emojis, storytelling, |

| 5 | 435 | 649.6 | The Media: TV, Radio, and Cinema | video, videos, viewers, |

| 6 | 358 | 511.99 | Information technology and computing | screen, upload, blog, website, web, digital, online, messaging, downloaded, computer, https, |

| 7 | 286 | 506.55 | Reciprocal | share, sharing, shared, shares, |

| 8 | 8194 | 406.27 | Pronouns | you, your, it, that, i, they, their, what, she, we, them, who, this, her, which, my, its, something, he, our, us, me, someone, his, one, everyone, everything, those, itself, these, anyone, anything, their_own, your_own, him, ones, whatever, yourself, |

| 9 | 731 | 402.12 | Paper documents and writing | post, posts, text, page, archive, posting, posted, list, delete, stickers, record, recording, edit, tag, deleted, |

| 10 | 503 | 279.17 | General appearance and physical properties | feature, image, twitter, images, features, format, ready, |

| 11 | 183 | 177.73 | The Media | media, publish, published |

| 12 | 31 | 147.6 | Business | rolling_out |

| 13 | 292 | 141.42 | Business: Generally | business, company, businesses, b2b, companies, |

| 14 | 542 | 135.72 | Time: Future | will, 'll, going_to, wo, soon, future, |

| 15 | 349 | 130.08 | Business: Selling | marketing, ads, customers, marketers, sales, buy, store, advertisement, advertising, |

| 16 | 326 | 123.31 | If | if |

| 17 | 619 | 115.73 | Wanted | want, choose, strategy, option, select, options, wanted, choice, |

| 18 | 443 | 113.1 | Sensory: Sight | see, watch, seen, watching, look_at, seeing, visual, watched, visible, |

| 19 | 1171 | 102.93 | Likely | can, would, could, may, might, ca, 'd, probably, likely, sure, make_sure, possible, clear, potential, |

| 20 | 428 | 100.83 | Time: Present; simultaneous | now, update, daily, yet, today, current, currently, updates, right_now, |

By mismatches, I mean tensions, glitches between the marketing rhetoric of Stories as a feature and the affordances offered for them.47 They are important indicators of the opaque agenda of apps and of their attempt to achieve potentially irreconcilable and competing goals: providing meaningful content to users, keeping them hooked on one platform at the same time as rendering their contributions monetizeable through advertising. These mismatches involve:

- A promised continuity of self that goes beyond the here-and-now and the apps’ logic of ephemerality and sharing the moment.

- The use of conventional definitions of stories as primarily verbal and textual activities and their design as primarily visual activities supported by a meta-language of visuality.

- The rhetoric of personalization, creativity, and control for the users, on the one hand, and the abundance of preselection templates and customization on the other.

Stories are launched as chronologically ordered collections of photos and videos with a beginning-middle-end and some continuity and permanence, which is from the outset defined as being relative to the single feed and the moment. For instance, in their inception, Snapchat Stories, were a way of going beyond the app’s pure ephemerality, by allowing users to post photos and/or videos that last for twenty-four hours, as opposed to being erased after they are viewed.48 In this way, Stories draw on conventional, accepted definitions that users can be expected to be familiar with. In the same vein as Stories on Snapchat and Instagram, the earlier discourses underpinning Timeline and Memories on Facebook are readily connectable with conventional conceptualizations of a story as a more permanent, temporalized, and ordered activity. We note then an association of memories and stories with the ideas of chronicling and archiving both today and “your past life.” This is, however, done in close association with the unit of moment and with posts, either previous or current, within a given platform. Memories on Facebook, for instance, are retrospectively put together by Facebook to include previous moments within Facebook: your posts and others' posts you're tagged in, major life events, and when you became friends with someone on Facebook. On the one hand, memories are designed as a retrievable archive of experiences, evoking a metaphor of memories with wide currency.49 On the other hand, they are still premised on and created out of past single feeds posted by users as a response to the directive of sharing the moment now.

It is notable that in the Ego Media corpus the lexeme moment(s) is one of the top 50 keywords, and it mostly collocates with share/sharing (see the table below). This suggests the close association of Stories with sharing moments, which is a far cry from the conventional definition of stories as reports of past events, evaluated and reflected upon by the narrator. (The association of stories with the past and past events is also noted in the reference corpora).

| Rank | Collocate | Freq. | logDice Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | share | 271 | 11.415 |

| 2 | day | 121 | 10.619 |

| 3 | 67 | 10.014 | |

| 4 | capture | 46 | 9.9 |

| 5 | all | 104 | 9.83 |

| 6 | sharing | 53 | 9.787 |

| 7 | life | 50 | 9.749 |

| 8 | lets | 39 | 9.549 |

| 9 | those | 47 | 9.523 |

| 10 | not | 79 | 9.422 |

| 11 | remember | 31 | 9.374 |

| 12 | in | 224 | 9.339 |

| 13 | their | 100 | 9.238 |

| 14 | from | 90 | 9.149 |

| 15 | everyday | 25 | 9.145 |

| 16 | throughout | 26 | 9.131 |

| 17 | capturing | 24 | 9.113 |

| 18 | of | 316 | 9.11 |

| 19 | the | 575 | 9.075 |

| 20 | that | 172 | 8.956 |

The sense of continuity which the launching of Stories evokes is therefore at odds with the continuing, algorithmically valued features of liveness of sharing, recency, and ephemerality. Snapchat Stories, for instance, remain live for twenty-four hours and then disappear. They are also literally small stories, that is, ten seconds long. And even though Instagram Stories can now be archived beyond twenty-four hours or be added to users’ profiles to appear as highlights, the algorithms still prioritize recency and newness in a number of ways. For instance, out of the people a user follows and Instagram thinks this user wants to see, the stories are ordered by time: whoever has posted most recently will be first in the feed. Putting together stories to go beyond the moment is therefore still done in ways that allow for aggregative compilations of moments in the present rather than for reflective, highly selective reconstructions of past events. This is evident in the most salient semantic categories relating to time and temporality in our corpus where there is a notable absence of the past. Instead, the present and its immediacy is foregrounded with lexical choices such as: now, update, daily, current, today, right now, new, recent, momentary.

| Semantic (sub)category | Words |

|---|---|

| future | will, ‘ll, going to, soon, future |

| present | now, update, daily, yet, today, current, currently, updates, right now |

| new | new, recent, young, original |

| latest, momentary | latest, momentary |

| momentary | moment, moments |

The emphasis on the present moment has implications for how features that promise more sustained story activities can be taken up by users. Kaun and Stiernstedt show that prioritizing recent posts and inviting users to constantly upload new materials is not conducive to collective remembering on Facebook.50 Flow, immediacy, and liveness are found to be major elements, not only in terms of how users are asked to participate in making memories, but also in how they experience time. In a similar vein, the analysis of the key semantic domains suggests that immediacy is a salient theme in the corpus: this can be observed in the highlighted semantic fields ‘Time: Future” (row 14) and ‘Time: Present; simultaneous” (row 20) below.

The salience of immediacy in the corpus is mainly supported by the aforementioned importance of the lexeme moment(s), which is in turn associated with sharing and capturing instants of one’s day and doing things/living/being “in the moment.” The most frequent modifiers for moment, often used in the plural, can be grouped semantically in three broad categories:

- everyday, little, casual, daily

- special, favorite, funny, beautiful, perfect, interesting, authentic

- fleeting, brief

| EgoMedia | BNC | English Web 2015 | TED_en | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collocate | Score | Collocate | Score | Collocate | Score | Collocate | Score |

| share | 10.55 | few | 9.15 | memorable | 8.63 | present | 9.58 |

| 10.13 | brief | 8.89 | very | 8.35 | brief | 9.16 | |

| everyday | 9.99 | very | 8.73 | present | 8.22 | very | 9.1 |

| favorite | 9.74 | fleeting | 8.1 | brief | 8.18 | exact | 8.93 |

| special | 9.19 | precise | 7.89 | pivotal | 7.97 | few | 7.34 |

| funny | 8.78 | crucial | 7.88 | few | 7.95 | great | 6.52 |

| brief | 8.7 | right | 7.75 | proud | 7.93 | ||

| life | 8.64 | last | 7.58 | teachable | 7.9 | ||

| behind-the-scenes | 8.58 | critical | 7.4 | dull | 7.51 | ||

| fleeting | 8.52 | present | 7.36 | crucial | 7.37 | ||

| particular | 8.46 | dipole | 7.28 | quiet | 7.37 | ||

| little | 8.46 | rare | 7.23 | watershed | 7.31 | little | 8.46 |

Moments are thus associated with spontaneity and the mundane, reinforcing the deployment of stories for sharing the everyday as it happens and as “multiple,” “little” moments. This is in contrast to the two most frequent meanings of moment in the BNC, namely moment as a very short time interval (e.g., a brief moment) and as an opportune and specific occasion (e.g., at the last/crucial/right moment). Such conventional associations for moment are absent from our corpus in favor of new associations, especially with the mundane.

In similar vein as for the lemma “moments,” the analysis of the collocates of the lemma story shows that the association between stories and memories, which is salient in the BNC, is absent from our corpus, providing further evidence for the close association of stories with the present moment and ephemerality. The fact that stories primarily collocate in the Ego Media Stories corpus with visual verbs (view, watch) as opposed to tell and hear is explained by the fact that stories are designated as a visual activity. The vocabulary, though, of telling stories in conversations with friends and the associating power of connections which this evokes is co-opted, as I show in the discussion of Mismatch 2.

| EgoMedia | BNC | English Web 2015 | TED_en | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collocate | Score | Collocate | Score | Collocate | Score | Collocate | Score |

| view | 11.45 | tell | 10.29 | tell | 11.34 | tell | view |

| 10.62 | 10.62 | 10.62 | 10.62 | 10.62 | 10.62 | 10.62 | 10.62 |

| watch | 10.87 | hear | 7.67 | read | 9.11 | hear | watch |

| 8.15 | 8.15 | 8.15 | 8.15 | 8.15 | 8.15 | 8.15 | 8.15 |

| tell | 10.84 | read | 7.59 | share | 9.03 | write | tell |

| 8.12 | 8.12 | 8.12 | 8.12 | 8.12 | 8.12 | 8.12 | 8.12 |

| create | 10.79 | write | 7.57 | hear | 8.19 | share | create |

| 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| see | 10.26 | recount | 7.39 | write | 7.79 | cut | see |

| 7.99 | 7.99 | 7.99 | 7.99 | 7.99 | 7.99 | 7.99 | 7.99 |

| post | 10.06 | believe | 7.37 | recount | 7.06 | remember | post |

| 7.31 | 7.31 | 7.31 | 7.31 | 7.31 | 7.31 | 7.31 | 7.31 |

| hide | 9.86 | invent | 6.77 | publish | 6.97 | know | hide |

| 6.52 | 6.52 | 6.52 | 6.52 | 6.52 | 6.52 | 6.52 | 6.52 |

| save | 9.55 | cut | 6.77 | retell | 6.95 | start | save |

| 6.2 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 6.2 |

| share | 9.38 | relate | 6.71 | narrate | 6.83 | be | share |

| 6.15 | 6.15 | 6.15 | 6.15 | 6.15 | 6.15 | 6.15 | 6.15 |

| bring | 9 | finish | 6.62 | know | 6.62 | make | bring |

| 5.84 | 5.84 | 5.84 | 5.84 | 5.84 | 5.84 | 5.84 | 5.84 |

| make | 8.88 | know | 6.59 | love | 6.46 | become | make |

| 5.67 | 5.67 | 5.67 | 5.67 | 5.67 | 5.67 | 5.67 | 5.67 |

| have | 8.53 | retell | 6.45 | relate | 6.3 | ||

| open | open | open | open | open | open | open | open |

| 8.17 | publish | 8.17 | publish | 8.17 | publish | 8.17 | publish |

| 6.39 | be | 6.39 | be | 6.39 | be | 6.39 | be |

| 6.29 | 6.29 | 6.29 | |||||

| delete | delete | delete | delete | delete | delete | delete | delete |

| 8.15 | continue | 8.15 | continue | 8.15 | continue | 8.15 | continue |

| 6.08 | move | 6.08 | move | 6.08 | move | 6.08 | move |

| 6.28 | 6.28 | 6.28 | |||||

| select | select | select | select | select | select | select | select |

| 8.11 | begin | 8.11 | begin | 8.11 | begin | 8.11 | begin |

| 6.02 | cover | 6.02 | cover | 6.02 | cover | 6.02 | cover |

| 6.21 | 6.21 | 6.21 | |||||

| be | 7.98 | illustrate | be | 7.98 | illustrate | be | 7.98 |

| 6.02 | break | 6.02 | break | 6.02 | break | 6.02 | break |

| 6.19 | 6.19 | 6.19 | |||||

| add | 7.97 | remember | add | 7.97 | remember | add | 7.97 |

| 5.97 | remember | 5.97 | remember | 5.97 | remember | 5.97 | remember |

| 6.05 | 6.05 | 6.05 | |||||

| tap | 7.81 | tap | 7.81 | tap | 7.81 | ||

| 5.95 | feature | 5.95 | feature | 5.95 | feature | 5.95 | feature |

| 6.03 | 6.03 | 6.03 | |||||

| download | 7.8 | narrate | download | 7.8 | narrate | download | 7.8 |

| 5.91 | run | 5.91 | run | 5.91 | run | 5.91 | run |

| 5.97 | 5.97 | 5.97 | |||||

| screenshotted | 7.54 | move | screenshotted | 7.54 | move | screenshotted | 7.54 |

| 5.85 | follow | 5.85 | follow | 5.85 | follow | 5.85 | follow |

| 5.94 | 5.94 | 5.94 |

The second mismatch in the data involves the way in which the label stories is deployed. On the one hand, it evokes conventional definitions of telling stories in other environments, particularly stories we tell our friends. The power of stories for connecting with others is also constantly referenced. On the other hand, the rest of the language that describes stories, the template stories that are offered as pictures or videos, and the actual facilities, designate Stories as postings with photos and videos. In this case too, Memories on Facebook provide a useful antecedent to this redesignation. Memories are described as a visual history of one’s life. Similarly, the term visual conversation with friends is increasingly employed by Instagram to describe users’ communication with Stories, in particular as one of the latest updates on offer allows viewers of a Story to respond to it with a photo or video. Language and text are increasingly confined to brief evaluative captions, ideally to be accompanied by emojis. As visual posts count as algorithmically priority posts, it is fair to assume that this serves as incentive for users to comply with the promoted visuality of Stories. It also consolidates the metricization of stories, adding yet another metric of success to the long-standing one of liking, that is, that of how many users have viewed “your story.”

This mismatch between the branding of stories and the affordances offered for them is also attestable in the parallel uses of the lexis Stories (with a capital S) and stories as two distinct and differentially defined activities. In the corpus, the former was found to refer to the engineered app feature that comes with specific affordances, while the latter, often prefaced by the pronouns my and your, evoked conventional definitions of stories that users are expected to be familiar with from other environments. Stories in the plural was also capitalized by 200 percent, while story was 50 percent more frequent than Story. The tables below show the frequency of each word form of the lemma STORY.

The lemmas story and stories strongly collocate with visual language (e.g., show, watch, view, hide) while story strongly collocates with tell and as, I show in Mismatch 3, with the theme of creativity too. Stories (both capital S and small s) also collocate with the verb use and the noun feature. This provides further evidence for the hybridity of the lemma story/stories as both a mode of creativity for the users and a curated feature as demonstrated by these tables, which show partial word sketches for the lemma story/Stories in the Ego Media Stories corpus

| Modifiers of ‘story’ | Nouns and verbs modified by ‘story’ | Verbs with ‘story’ as object | Verbs with ‘story’ as subject | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collocate | Score | Collocate | Score | Collocate | Score | Collocate | Score |

| snapchat | 10.96 | Explorer | 9.92 | view | 11.45 | be | 9.74 |

| 10.76 | Settings | 9.56 | watch | 10.87 | play | 9.51 | |

| own | 10.17 | Feature | 9.55 | tell | 10.84 | end | 9.48 |

| entire | 9.96 | Setting | 9.42 | create | 10.79 | include | 9.28 |

| my | 9.39 | Post | 9.34 | see | 10.26 | follow | 9.08 |

| new | 8.83 | Click | 9.12 | post | 10.06 | disappear | 8.98 |

| first | 8.79 | highlights | 8.79 | hide | 9.86 | use | 8.65 |

| snap | 8.6 | Content | 8.63 | save | 9.55 | have | 8.51 |

| ig | 8.46 | tomorrow | 8.58 | share | 9.38 | appear | 8.49 |

| current | 8.4 | Today | 8.55 | bring | 9 | ||

| custom | 8.35 | Saver | 8.54 | make | 8.88 | ||

| next | 8.31 | Takeover | 8.49 | have | 8.53 | ||

| Modifiers of "Stories" | Nouns and verbs modified by "Stories" | Verbs with "Stories" as object | Verbs with "Stories" as subject | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collocate | Score | Collocate | Score | Collocate | Score | Collocate | Score |

| 13.11 | Feature | 11.12 | use | 11.69 | be | 10.97 | |

| snapchat | 11.22 | highlights | 10.53 | introduce | 10.02 | have | 10.17 |

| 9.39 | everywhere | 10.31 | view | 9.91 | allow | 10.14 | |

| live | 8.07 | Archive | 9.66 | watch | 9.67 | do | 9.28 |

| custom | 7.74 | Format | 9.31 | launch | 9.55 | let | 9.2 |

| official | 7.64 | Ad | 9.26 | post | 9.39 | launch | 8.79 |

| our | 7.59 | Camera | 9.04 | share | 9.37 | become | 8.76 |

| search | 7.52 | Screen | 9.01 | create | 9.31 | make | 8.75 |

| stories | 7.37 | Ads | 8.71 | see | 9.16 | provide | 8.74 |

| view | 7.26 | snapchat | 8.63 | make | 9.08 | appear | 8.73 |

| feature | 7.12 | Work | 8.56 | call | 9 | give | 8.68 |

| insta | 7.03 | Section | 8.55 | save | 8.85 | offer | 8.52 |

The analysis of tell+story concordances suggests that telling a story is presented as a key element of a successful Story: “There’s no better way to put a human face on your brand than by telling a story”; “For your Story…Tell a story!” But telling a story refers, in this context, to visual storytelling as can be seen by its association with lexis of visuality: “Instagram is a visual story telling tool”; “Marketing is about telling stories, and few things tell a story faster than a picture”; “Brands have started to love that they can finally tell a story without writing a 400-word post on Facebook.”

In addition, the analysis of tell+story and good+ story concordance lines suggests that telling a (good) story involves:

- organizing images or videos in chronological order to form a a coherent sequence: “By stringing together selected ‘snaps’ (their videos and images) users can create a chronological narrative of their day that can be viewed for 24 hours”; “Put together an Instagram Story that actually tells a story”; “Every good story has a beginning, middle, and end.”

- engaging followers through personalization, authenticity: “Tell your/their (own/unique) story” and originality: “You can become a great storyteller by giving new and exciting vantage points to your product. Being authentic on Instagram is what users crave”; “A good Instagram story is a quick idea, coupled with some creativity.”

- using text, filters, and other such features to make the visual story more coherent and engaging: “The use of text adds context to your Instagram Stories – helpful when the photo cannot tell the story on its own”; “A good story includes video, imagery, text, and decoration.”

The above associations suggest that the power and creativity of “telling stories” is co-opted in a visual medium where stories as a feature are actually designed as primarily visual rather than textual communication. The visuality of stories in turn places a premium on specific narratorial positions, in particular, the narrator-experiencer as opposed to the narrator who can step back and reflect on the goings-on. The privileging of sensory roles for the narrator-recorder of their life (e.g., I see, I hear, I am experiencing now) becomes part of the key semantic domain of visuality. Similarly, audiences are positioned as primarily viewers of stories. The experience and language of watching a TV series or film language are adapted in the offered facilities and so, for example, Stories can be viewed, hidden, watched, muted, rewound, etc. In the Ego Media Stories corpus, most of the sensory-visual verbs (watch, see, view) position users as consumers. This tallies with the marketing purposes of Stories, as I discuss in Mismatch 3 below, and it adds to the overall mismatch between Stories as a feature and the rhetoric that stories as a label evoke.

The third mismatch involves the rhetoric of personalization for users, which highlights that they are in a position to control their stories and be content creators, with the high level of standardization with which stories come, especially in terms of preselections. A key linguistic element of personalization in the corpus involves the unusual frequency of the second person pronoun you, which is approximately five times more frequent than I. (Your is about ten times more frequent than my, as the table below – Top 10 most frequent pronouns in the Ego Media corpus – shows.

The salience of you and your can be partly explained by the fact that many of the articles are how-to guides, containing numerous indications and procedural sequences, and are written in a style that directly addresses the users. At the same time, the analysis of you collocates suggests a strong association between you if-conditionals and modals. All three categories emerged from the keyword analysis as salient features of the corpus. The fact that they are also closely connected as collocates suggests an emphasis on the choices and possibilities that Stories as a feature offer to users.

At the same time, choices in the corpus seem to be restricted to predefined options or scenarios that allow specific courses of action in specific circumstances, as we can see in the table below:

| 1 | just tap their faded profile photo to send a quick response. | You | should see the new disappearing photos and videos feature |

| 2 | IGN Is Now On SnapchatShare. Oh snap. Oh snap. Update: If | you | haven't checked out IGN's Snapchat edition, you are |

| 3 | has a feature that allows you to add music or sound effects. | You | can even use your own playlist, although it does add |

| 4 | into GIFs and post them on your Instagram Story, even if | you | re not using Instagram's standalone GIF-creating app |

| 5 | of friends or brands that would start group chats if | you | reply (Instagram) Surely Messenger Day will adopt these |

| 6 | the attention of the teenage and under-35 markets. If | you | re looking for a digital marketing agency that keeps their |

| 7 | clicking on the icon, you will be redirected to a page, where | you | can either enter or paste the URL that you want your |

| 8 | TIPS: If you get bored with one of the snaps within a story, | you | can use your other hand to tap the screen and it will |

| 9 | Insta stories had the most impact. With #InstaStories | you | can create impactful #videos that resonate with your |

| 10 | if there is any way they can watch Live Stories anonymously. | You | would want to do this when you are 'stalking' or 'checking up |

The theme of possibilities for users through Stories is also closely linked with another salient theme in the corpus, that of creativity, authenticity, and originality. Authenticity in particular is presented as a core feature of the story design as a result of Instagram in particular appearing to have taken on board the backlash from posting “glossy, perfect lives” 51 and the moral panic about posting edited selfies as a narcissistic activity.52 In this way, story design seems to be picking up on a prevalent discourse in the aftermath of this moral panic about the need for online self-presentation to be authentic and “real.”53 Stories come to remedy an earlier emphasis on edited selves. The directive to “keep it real” and be original, however, is at odds with the emphasis on customization and preselection templates, as I show.

Authenticity is stressed through its collocations with spontaneity and the users (ordinary users and businesses alike) affording their followers a behind-the-scenes feel of their everyday life.

| Rank | Collocate | Freq. | logDice Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Being | 3 | 9.299 |

| 2 | spontaneous | 3 | 9.254 |

| 3 | raw | 3 | 9.133 |

| 4 | tell | 8 | 9.011 |

| 5 | feel | 7 | 8.784 |

| 6 | rather | 4 | 8.687 |

| 7 | nature | 3 | 8.654 |

| 8 | storytelling | 3 | 8.613 |

| 9 | brand | 12 | 8.362 |

| 10 | visual | 3 | 8.346 |

| 1 | to build a relationship with their customers through | authentic | and personal content. Indeed, Brian Robbins of |

| 2 | Footage The key is to make your fans feel like insiders. | Authentic | , behind-the-scenes content does just that. This is the |

| 3 | to post content that is real-time, spontaneous and more | authentic | . For brands there are a number ways Instagram Stories can be |

| 4 | and viewing Stories, you were sharing and viewing more | authentic | moments in someone's life. It's messier. It's maybe |

| 5 | for a company is to tell original stories that reflect | authentic | moments, instead of the traditional publicity that can be |

| 6 | contests and campaigns, and drive more engagement. | Authentic | and visual brand storytelling is the future of marketing, |

| 7 | pictures of food and drink, an actual story that conveys an | authentic | narrative has a strong chance of standing out. Adding |

| 8 | on popular user behavior, 2. It's a great way to share more | authentic | moments with followers, and 3. This means one less social |

| 9 | stories," says "Today's marketers need todeeper more | authentic | stories," says Craig Elimeliah , Director of Creative |

| 10 | re asking that because everything in my mind is about real, | authentic | engagement. So you need to ask some questions and you need |

Similarly, keywords and phrases, such as create, creative, much creativity, creating content, own story, exclusive content, indicate emphasis on using the Stories feature creatively and on being authentic and original. This is certainly how Stories were initially promoted by Instagram: the phrase much creativity occurs twenty-nine times in the corpus, each occurrence being the result of citation (i.e., the articles cite Instagram’s announcement at the launching of Stories). Creativity collocates with the term story in association with possessive modifiers (my, your) while, as suggested above, Stories collocate with the words feature and use. This positions posters of Stories as both creators of content (storytellers) and as users and consumers of a curated feature. This tension between productive, personalizing, and curated roles is also evident in the uses of the keyword creative. The analysis of its most significant collocates suggest three main patterns of use:

- Collocates such as Get, get, Be indicate that creative is frequently used in imperative sentences/headlines (see Top 20 collocates for creative, lines 1–3)

- Collocates such as tools, way, ways, filters, content suggest that creative is frequently used to refer to the creative potential of Instagram/Snapchat tools (see Top 20 collocates for creative, lines 4–7)

- Creative is most frequently associated with adjectives such as fun, funny, and engaging (see Top 20 collocates for creative, lines 8–10)

| Rank | Collocate | Freq. | logDice Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Get | 32 | 10.693 |

| 2 | tools | 41 | 10.655 |

| 3 | get | 51 | 9.711 |

| 4 | ways | 25 | 9.672 |

| 5 | fun | 25 | 9.599 |

| 6 | Be | 13 | 9.403 |

| 7 | Tools | 9 | 9.158 |

| 8 | funny | 10 | 9.048 |

| 9 | engaging | 10 | 8.872 |

| 10 | more | 56 | 8.848 |

| 11 | process | 9 | 8.769 |

| 12 | way | 29 | 8.674 |

| 13 | ideas | 8 | 8.642 |

| 14 | with | 87 | 8.611 |

| 15 | filters | 15 | 8.595 |

| 16 | creative | 10 | 8.478 |

| 17 | use | 28 | 8.424 |

| 18 | content | 34 | 8.398 |

| 19 | be | 55 | 8.311 |

| 20 | ! | 22 | 8.225 |

| 1 | provide prizes to the first person to find the answer. Get | creative | , like Travel+Leisure did, and watch your audience |

| 2 | media habit if you want to take this medium seriously. Get | creative | . Repetitive content is what kills long-term engagement. |

| 3 | are the types of questions marketers have to ask. Push Your | Creative | Side By giving a reason to follow the content, more users |

| 4 | want to keep on your profile grid. Edit them with filters and | creative | tools and combine multiple clips into one video. - Share |

| 5 | unique. Via spingo: Snapchat geofilters In order to add | creative | design options to your event specific geofencing, follow |

| 6 | weekly themed content, and so on. Conclusion There are many | creative | ways to incorporate the new Highlights feature into your |

| 7 | in your videos, giving you so many possibilities for | creative | content. Use your imagination! We've got some pawtastic |

| 8 | these fun Snapchat ideas a try. Here are seven unique and | creative | uses of Snapchat for your business. 1. Coupons The |

| 9 | ideas out on Snapchat? Snapchat allows you to share fun, | creative | , and personable content quickly and interact with your |

| 10 | help you make any photo or video funny, interesting or | creative | ." GIF stickers in Instagram are already available today as |

Another keyword in the corpus which shows the same tension between individual creativity and customization is own, and, respectively, the key phrase own story. A concordance and collocation analysis of own has highlighted the following patterns of use:

- own used with a reflexive sense (watching/viewing your own content/profile):

- “When viewing your own story, you can swipe up to see who has viewed each of your photos and videos.”

- customization – using different tools to personalize stories:

- “You can also create your own geofilters for Snapchat.”

- “These features are a great way to add your own spin to the images you send.”

- authenticity (telling one’s own, unique story):

- “Got your own story to tell about how to use Instagram Stories to its full potential?”

The above examples and collocates show the coexistence of creativity that promises choice and control for the storyteller with designed preselection facilities which restrict control to choosing from a menu, adjusting privacy settings, turning notifications on or off, etc. In a similar vein, Stories come with an abundance of constantly evolving tools that are widely adopted by users. These include:

- Augmented reality filters such as koala ears and rainbow barfs

- Bespoke graphics and emojis

- Time and scene duration manipulations, for instance, flipograms and boomerang which allows forward and backward movement

- Template stories and style guidelines

- A menu of voices for users to choose for themselves as a character in their story.

Stories thus function as a site for intensifying curation by pulling together (cf., bundling) complex resources and tools. According to Poulsen’s study of the history of the design of Instagram, this is in tune with the gradual evolution of Instagram from a photo-sharing app to a social network app with social interaction at its center: Stories have been an important step in this evolution.

Both the abundance of story facilities and the mismatch between the rhetoric and the reality of creative control for the users are comparable with what has been noted about Mark Zuckerberg’s “user-empowering language” about sharing on Facebook.54 Freishtat and Sandlin specifically argue that the illusion of control for users is achieved by simplifying and diversifying tools for managing content at the same time as rhetorically positioning them on the same plane as would-be content exploiters. As seen, both strategies apply to the data at hand. In particular, there is a strategic ambivalence in our corpus about who is addressed: ordinary users, influencers, and businesses alike are positioned as level-playing content producers. At the same time, ordinary users are the ones targeted by the advertising through Stories. The positioning of users as both story creators and consumers ultimately enhances the mismatch between the rhetoric and reality of control.

Why are these mismatches in play? And what do they tell us about the direction of travel in relation to designing stories on media apps at this point? What kinds of stories, lives, and subjectivities does this designing have the potential to make more visible, available, and perhaps sought after? At the heart of these questions is our finding that the apps’ curation of stories capitalizes on familiar, positive associations of stories with personal creativity and connection with others, through sharing experiences. This suggests that, from the outset, stories are viewed as an attractive communication format in the quest of apps for serving as hubs which keep the users hooked.55 What better way for it than providing facilities that encourage users to present themselves with some kind of continuity, as van Dijck observes about Facebook and LinkedIn?56 The mismatches reported, however, show that using stories as a vehicle well-suited to the provision of facilities for meaningful content creation is connected with the apps’ dual and often competing goals of design and algorithmic maximization. In particular, with Stories, media companies appear to be taking a further step toward the algorithmic microtargeting of users with advertisements. Stories both in terms of what they reveal about the users and in terms of how they can be used by business are seen as a more personalized and compelling way of advertising.57 The analysis of the business and marketing key semantic domains in the corpus provides further evidence between the close links between stories, advertising, and metricization.

We observed evidence of marketization and metricization at different stages of the analysis. In particular, the analysis of keywords and key semantic domains revealed a range of terms and expressions (e.g., brands, marketing, marketers) which suggest that many of the articles in the corpus address those marketers who (intend to) use Instagram/Snapchat Stories so as to promote their brands.

In a second stage of the analysis, we looked at the 100 highest ranked key words (by score value) and their collocates. The strong association between the words platforms, creative, and content with their respective collocates/collocations advertising/marketing platforms, creative marketing, creative brand, and deliver content, produce content, consume content, promote content strengthens the observation that marketization is a salient theme in the corpus and that the Stories feature is presented as an instrument of marketization.

The words followers, engagement, users, post and their collocates suggest that the Stories feature is also discussed in the articles from the corpus in relation to metricization. Metricization seems to involve gauging audience size and levels of engagement, as well as the number and frequency of posts. The lexis of metricization thus involves:

- nouns such as: count, growth, metric, numbers, rate

- quantifiers: more, high, as much as

- numerals: x million, x [times]

- frequency adverbs: regularly, frequently, consistently

- verbs: gain, engage, grow, build.

Metricization in the corpus also strongly collocates with sensory (visual) verbs. In particular, the keywords see, view, and watch frequently co-occur with wh- words and quantifiers (e.g., many, number, times) to form recurring multiword sequences (e.g., see who has viewed your story, see how many people have viewed your story). Engagement with a story and enjoyment out of it thus becomes a measurable, status-accruing activity.

| 1 | well, anyone can choose to to follow you. To see who has been | viewing | the snaps on your story, go to the Stories screen as |

| 2 | rates. Yes, you are able to take a look at how many people | viewed | your story on Instagram, however, you can't see how |

| 3 | away views from stories. Generally, I receive about 100 | views | if the first two or three minutes after I post a story. Today |

| 4 | how many times an Instagram video or image in their feed was | viewed | more generally, according to the number of "likes" it |

| 5 | , this is probably a great way to up its numbers and get more | views | to more stories, but the costs (to people's time?) might be |

| 6 | you to see how many times your video was viewed and who | watched | it. Marketers can get a better idea of their interacting by |

| 7 | before they disappear completely. Also, whenever you | watch | a friend's story it notifies them that you've seen it.. Well |

| 8 | story has been seen. This is a good way to see if people are | watching | your story multiple times , which may mean that they are |

| 9 | there (read: 1762) is the total number of people who have | watched | your stories so far. While you're watching InstaSnap (I |

| 10 | Instagram feed, if you fancy. Can I see how many people have | watched | it? Again, yes. When watching your own story, at the |

Based on keyword and key semantic domain analysis in the corpus, metricization does not seem to emerge as a salient theme. Nonetheless, its saliency becomes visible when looking at specific keywords and their collocates. For instance, terms such as followers, engagement, users, and audience seem to be frequently associated with numerals and quantifiers, but also with nouns such as count, growth, metric, numbers, and rate. As I have shown, the sensory verbs view, watch, and see were also found to frequently collocate with quantifiers (many, number, times). These associations suggest that quantification is a recurring trend in the corpus, particularly in the context of measuring and growing audience size and leveraging engagement.

To make the significance of metrics and metricization in the corpus more visible, we explored the theme with the help of automated thesauri (automatically generated list of synonyms and/or semantically related terms). The thesaurus function works by grouping a word’s collocates based on their grammatical function (i.e., generating a word sketch) and then comparing these collocates with the collocates of all the words in the corpus that belong to the same part of speech. What this means is that thesaurus groups together words that are found in similar contexts.

| Lemma | Score | Freq |

|---|---|---|

| chance | 0.155 | 203 |

| frequency | 0.145 | 20 |

| count | 0.141 | 89 |

| ratio | 0.14 | 39 |

| engagement | 0.132 | 490 |

| reach | 0.125 | 165 |

| view | 0.124 | 615 |

| level | 0.113 | 148 |

| base | 0.11 | 163 |

| growth | 0.104 | 196 |

| impression | 0.102 | 85 |

| impact | 0.101 | 84 |

| number | 0.1 | 581 |

| like | 0.097 | 144 |

| score | 0.093 | 60 |

| clone | 0.093 | 80 |

| bar | 0.093 | 164 |

| kind | 0.093 | 229 |

| problem | 0.092 | 165 |

Here is a Thesaurus for rate (NB: we only chose the top 20 synonyms, as relevance decreases with score):

- rate occurs 148 times in the corpus, and it forms associations such as: completion rate, conversion rate, engagement rate, growth rate, interaction rate, retention rate, swipe-through rate;

- other similar words (and common collocations) highlighted by the thesaurus include:

- count (view count, follower count)

- chance (give you the chance, chances are)

- ratio (aspect ratio)

- reach – similarity based on increase, have, be (organic reach, increasing/extending/expanding the reach –> x is a way to increase your reach)

- view (X views per day, received/got/had x views, engagement and views, camera view, grow views, how many views, get more views, the amount/number of views, point of view, Snapchat story view counts, how to view, unique views, total views, your views, x video views)

- level (deeper level, a whole new level of, take things to the next level, a more personal level, level of engagement/intimacy)

- base (customer/consumer/fan/follower/(active) user* base; increase, expand/massive user base)

- growth – user growth, growth strategy, growth rate, follower growth, audience growth, Snapchat’s growth, rapid/tremendous growth

- impressions (reach and impressions, made an impression, number of impressions, under the impression)

- impact (make an/a bigger impact, measure impact, maximize impact)

- number (total number of, number of times, number of views/viewers/users)

- likes (like and comments, likes and followers, no likes or comments)

- score (Snapchat score)

- clone (“Instagram Stories being a clone of Snapchat Stories”)

- bar –> “[Stories/followers] displayed in a bar at the top of your feed”

As can be observed, not all these words represent metrics, but they are all associated with measuring and increasing user engagement.

The analysis of sensory verbs, the themes of marketization, and the quantification of audience engagement clearly show that the social aspects of stories as a feature become intertwined with the quantifiable. Following Lupton’s adaptation of the notion of commensuration,58,59 we can describe the relationship between metricization and audience engagement in the corpus as commensuration: the two themes represent fundamentally different qualities which come together in ways which both confer some kind of homogeneity on their diverse meanings and begin to produce new forms of understanding them. Put differently, numbers of views in stories become commensurate with audience engagement and involvement in a story.

This infrastructure in which social interactivity and affectivity are instantly turned into valuable consumer data has been argued to be intensified by Facebook through multiple actions that are afforded by convergence and cross-syndication of apps. Users’ navigation between related apps ultimately feeds data back into Facebook.60 Such dynamics of intensification shows that the collapse of the social with the quantifiable and traceable is designed on social media as an ongoing and potentially scalable process.61 The ways in which friendship and followership are computed on Facebook and Instagram are clear antecedents of the quantification of social relations we note in stories too, directing users to reimagine them.62 The commensuration of engagement and metricization in stories is also also in tune with Abidin’s claim that the attention economy is currently conflated with the affection economy on social media.63

In view of the above, the reported mismatch between the rhetoric of control for the users and the reality of designed templates can be explained by the role of metricization both as traceable behavior and as a way of capturing users’ attention in the curation of stories. Stories become integrated into an ever-evolving metricization, sedimenting users’ quantified self-presentation. It is true to say that facilities for audience selection are constantly being rolled out: for example, users can include ten friends by mention in their Instagram story, and these become their ratified addressees. But the dilemmas of audience selection vs. audience reach persist, as stories vie for viewings from as many friends and followers as possible. The uptake of Stories is in turn intertwined with visible (to users) metrics, including not just numbers of views but also of viewing completion figures. It is clear that metrics in stories have been designed so as not just to capture attention but also to retain it, maximizing the followers’ time spent on engaging with them. The shift to a streaming culture typified by stories is also aimed at keeping both posters and followers active and coming back.64 The recent evolution of Instagram, of which stories are a pivotal point, has been analyzed through the lens of curtailing cross-platforming: Instagram wants users both to content dump on its platform and to post more frequently by breaking the previously established practices of users posting only at optimal times.65

This metricization of stories is a factor in their huge success as a feature amongst celebrities and influencers who can use them so as to blur the boundaries between sharing snapshots of their mundane everyday with promoting their products. Similarly, established brands are now being promoted by advertisers through Stories. The constant rolling out of features which facilitate this is indicative of where stories as a communication feature are going to next. For instance, the Paperclip icon on Snapchat lets everyone, from ordinary users to advertisers, attach an external web link to their Snaps for their Stories. It is fair to assume that connecting their presence on Snapchat to other locations on the web is mostly done for the benefit of corporate brands and that, increasingly, users will be encouraged to go to the websites of such brands to check out products. It is no accident that over 50 percent of businesses on Instagram have produced a Story on the platform and one in five Stories from businesses generate a direct message from a follower, potential client, or customer. 66

In this project, I set out to address the question of what definitions and views of stories underpin the increasing offering of story features on apps. Similarly, I asked who is positioned as an (ideal) story creator and audience of those stories and why? I focused on the feature of Stories on Instagram and Snapchat. My corpus-assisted critical analysis of how the apps’ publicity and other online media present and review Stories, including a keyword analysis and identification of the lexical and thematic associations of the word story/ies, made apparent a notable convergence on how they are conceptualized in the two apps and what kinds of affordances are offered for them. In particular, the explicit design of stories as an accumulation of moments was found to come with certain paradoxes and mismatches between the rhetoric of the design and the affordances.

Stories were found to be built on the basis of the algorithmic logic of instant live-sharing despite setting out to go beyond the moment and to offer facilities for continuity of self.

Stories promoted visual representations and snapshots of sharing the moment as well as viewing audience engagement practices, despite evoking familiar tropes of textual and telling accounts of one’s life.

The promise of user control and creativity was found to clash with the abundance of preselections, prior categorizations of experience, templates, and menus with specific editing features.

I argued that these mismatches show a collapse of the relational and creative power of stories with the quantification of users’ activities. They thus attest to the increasing links of story curation with the social media move toward monetized, advertising-linked design. The hybridity of Stories as content-creation features and consumables is also evidenced in the ambivalent positioning in the corpus of the target users of Stories as (ordinary) creators, advertisers, and consumers.

Taking into account the media affordances of distribution and amplification, this curation of stories has the potential to create normative ways of storying oneself. Similarly, the convergence and replication of story facilities across apps suggests that drawing on templates to post stories will become further consolidated as a widely available mode of sharing everyday life, particularly for the main targeted groups of teenagers and young adults. The marketing of Stories already makes specific assumptions about what is story-worthy. In particular, template stories offered by the apps and how-to-guides are about sharing moments of having fun with friends. The features that enhance the stories’ plot involve adding weather, location, holidays, funny sunglasses, etc. Users are encouraged to create “goofy selves” and to do “imperfect sharing.”

Overall, any further curation to stories can be expected to continue to navigate the slippery ground between the provision of meaningful, personalized content creation which aims at maximizing users’ attention economy within an app and the monetization and metricization of lives which capitalizes on this attention. Stories provide ample opportunities for further collapse of the relational with the quantifiable and of the attention with the affection economy.

The deployment of stories in processes of subject-making, especially in the production of entrepreneurial subjects who seek mobility, has lately been noted in relation to many contemporary institutional practices in Western contexts: from legislation and production and circulation of stories in legal hearings to electoral processes and voter canvassing. The critique of this commoditization of stories which often involves scripted performances fashioned in the self-help industry points to a reduction of the vastness of narrative practices and the fullness and complexity of individual experience.67 This complexity is skewed through the use of dominant narrative devices and plots that make certain stories legible and amenable to traveling beyond their original contexts into the mainstream.68,69 Stories on apps, as discussed and analyzed in this project, need to be placed in such contexts of neo-liberalization, where stories have been refashioned since the turn of the millennium within a business model, so as to bring capital to organizations. The close association of stories with the social media economy of sharing, however, as shown, allows the commoditization of stories to take a decisive step further than the self-help industry of globally available training toolkits and protocols produced in the last twenty years. To be specific, the previous context of commoditization and marketization of relations of emotions and friendships, for instance on Facebook, needs to be taken into account as a strong antecedent. It has been amply argued that this commoditization privileges pro-social positive emotions and has the power to regulate the diversity of content within the ubiquity of Like economy.70 Stories are placed within this, in some ways inescapable, genealogy. In addition, the wide availability of ready-made, preselection templates, ideally brief and portable for easy distribution, can be expected to commoditize stories even further, rendering the reported mismatches, especially between curation and creativity and uniqueness, more apparent and potentially more difficult for the users to reconcile. Stories are designed in ways that illustrate a process of templatizing and genericizing which is the very definition of branding: “the reckoning of commodities, or elements of them, by their loose affiliation to authorized brand instances through fractional similitude with them (in a formal structural or design sense).”71 By acquiring sociotechnical aspects and becoming integrated into the architecture of apps, stories as designed features thus create parameters and preferences for specific content posting, posting practices, and self-presentation. This is not to suggest that users’ practices based on story features will not present contextual and individual variation in how different users may take them up. Individual users’ creative practices notwithstanding though, the level of standardization reported here merits further critical attention if we are to understand fully the place of stories in the social media curation of lives.

Endnotes

- Cited in Josh Constine, “Instagram Launches ‘Stories,’ a Snapchatty Feature for Imperfect Sharing,” TechCrunch (blog), 2016, http://social.techcrunch.com/2016/08/02/instagram-stories/. ↩

- S Cooper, “Snapchat versus Instagram: The War of the Stories,” 2016, https://www.thedrum.com/opinion/2016/08/25. ↩

- Mansoor Iqbal, “Instagram Revenue and Usage Statistics,” Business of Apps, February 8, 2023, https://www.businessofapps.com/data/instagram-statistics/. ↩

- Ash Read, “Instagram Stories: The Complete Guide to Use IG Stories to Boost Engagement for Your Brand,” Buffer, March 16, 2023, https://buffer.com/library/instagram-stories/. ↩

- Site no longer available, but see web archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20171223065900/http://www.rubhusocial.com/a-beginners-guide-to-instagram-stories. ↩

- See https://help.instagram.com/1533933820244654. ↩

- For details on the role of metrics in the ecology of storytelling and engagement with it, see Alexandra Georgakopoulou, Stefan Iversen, and Carsten Stage, Quantified Storytelling: A Narrative Analysis of Metrics on Social Media (Palgrave Macmillan, 2020), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-48074-5. ↩

- Sherry Turkle, Life on the Screen: Identity in the Age of the Internet (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995). ↩

- Rob Kitchin and Martin Dodge, Code/Space: Software and Everyday Life (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2011). 41. ↩

- David Beer, “Power through the Algorithm? Participatory Web Cultures and the Technological Unconscious,” New Media and Society 11, no. 6 (September 1, 2009): 985–1002, https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444809336551. ↩

- Tarleton Gillespie, “Algorithm,” in Digital Keywords: A Vocabulary of Information Society and Culture, ed. Benjamin Peters (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2016), 18–30, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvct0023.6. ↩

- Deborah Lupton, The Quantified Self (Cambridge: Polity, 2016). ↩

- Jose van Dijck, The Culture of Connectivity: A Critical History of Social Media (Oxford University Press, 2013), https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199970773.001.0001. ↩

- Taina Bucher, If...Then: Algorithmic Power and Politics, Oxford Studies in Digital Politics (Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2018). ↩