Showing the Moment

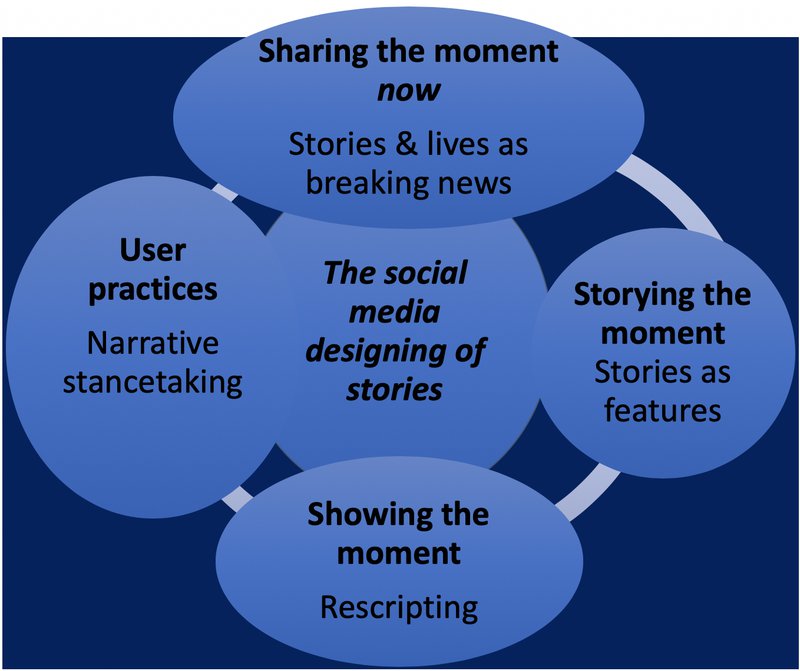

My genealogical tracking of ego-centered apps (mainly Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat) combined with the analysis of users’ communicative practices has allowed me to identify three pivotal design phases in their evolution concerning facilities for the presentation of self through (small) stories (see figure 1). Each of these phases is connected with the development of specific story genres, storyteller positions, and audience uptake for each of them. The first design phase goes back to the inception of social networking sites as spaces for sharing the moment now, with a premium on brevity and based on an algorithmic pressure for immediacy. I have demonstrated how this economy of breaking news serves as a directive to users for sharing their everyday life as small stories, that is, as brief, fragmented, share-as-you-go snapshots of daily, often mundane, life (see Sharing the Moment Now as Breaking News). With data from Facebook and YouTube, I have also shown the salience of the user practice of taking a narrative stance on unfolding events. Elsewhere, I focus on the third and more recent design phase (covering mainly the period post-2015), which I describe as a story-designing spree, as it involves the rolling out of facilities, explicitly branded as memory and story facilities.

The second major design phase which I focus on here, has involved the move from telling the moment, with text-based representations, to showing the moment. This was enabled and encouraged with facilities for geolocation, shared check-ins, and visual affordances, in particular selfies, which rose in popularity in 2013. The role of language in this predominantly visual multi-semioticity becomes confined to brief captions, normally overlaid onto images and serving as stage directions or assessments of what is shown: see section on Showing, (hyper)visibility, and the move to authenticity. Prompted by this shift toward a digital visuality, I decided to look into selfies as a major app-engineered technology of the self.

When I embarked on the Life-Writing of the Moment Project, I could not have anticipated that a study of selfies would be part of it. What we had to grapple with, individually and collectively, in the course of the Ego-Media project, was the sheer quantity and velocity of changes in the social media landscape, too significant to ignore but at times too difficult to balance with the slowness and painstaking analysis that our research methods necessitated. The speed with which selfies seemed to become a ubiquitous self-presentation modality, especially for the young women who were their early adopters, took me by surprise. At the same time, it conformed with the shift from sharing the moment as breaking news to showing the moment and oneself in it, to which my tracking of the evolution of platforms was attesting. In sociolinguistic terms, selfies very quickly underwent a process of enregisterment,1 that is, of having become associated with particular social practices and types of people engaged in such practices. This was evidenced in a rapidly developing selfie-related lexicon (e.g., a selfie moment, selfie addict, belfie, mirror selfie, etc.) and in proliferating public discussions about selfies, many of which pathologized them and their users.

As a result, my decision to include an exploration of selfies in my project was partly prompted by what I saw as a need for empirical studies on a phenomenon which seemed to produce in accelerated terms both practices for posting selfies and a particular discourse, amongst lay and academic commentators (e.g., in social psychology and psychoanalysis), that converged on a dystopian view of selfies as female narcissism, linked with body image disorders and the disruption of “social relationships.”2 This discourse – given that the primary selfie-takers and early adopters of selfies were young women – echoed other pathologizing discourses about young women and drinking, clubbing, etc. Cultural studies analysts have claimed that such discourses could be viewed as a backlash of the postfeminist emancipatory ideal of the (hyper)visibility of young women in the public sphere.3 In the case of selfies, there was an immediate contradiction between such discourses and the fact that “top” selfies charts tended to be populated not just by female celebrities’ selfies but also by group selfies in which male public figures (e.g., politicians) and celebrities constructed ordinariness: for instance, Ellen DeGeneres’s Oscars selfie (2014).4

With the above as the point of departure, I embarked on an empirical study of selfies posted on Facebook, then the main space for ordinary users’ posting selfies.

Taking a perspective on selfies as small stories recognized narrative stancetaking as an important aspect of posting selfies in context and for specific audiences (viewers). Storying in selfies was thus viewed as a dynamic, contextually emergent process, co-constructed by selfie-posters and users that engage with them, rather than as an all-or-nothing, ontological, and a priori definition of a selfie as being or not being a (small) story.5,6 Specifically, with a small stories perspective, the subjectivity of selfies becomes part of a contextual and interactional analysis that seeks to explore the partly conventional, partly contingent links amongst ways of telling (the communicative how), social media affordances and constraints, and selfie-posters as communicators, social actors, but also individuals with biographical repertoires – see the section Analyzing stories and identities in interaction. Positioning analysis, as developed within interactional approaches to narrative and identities,7 combined with a social semiotic analysis of selfies as multi-semiotic activities, provided a useful heuristic for studying how, with what semiotic choices, selfie-posters present themselves.8 The analysis showed that selfies came with media-shaped narrative potentiality, e.g. Facebook-designed narrative stancetaking elements, which routinely led to co-authored and expandable small stories through audience engagement.

The material I used for the study of selfies was based on selfies by female and male teenagers, and it was the result of an (auto)-ethnographic tracking of my, then teenage, daughter’s circle of friends.9 As part of this ethnographic process, I involved my key informants in discussions about a possible approach to selfies, asking them to assist me in formulating some kind of a typology of selfies that captured their main visual arrangements in combination with what they commonly aimed to achieve. Perhaps unsurprisingly, their own descriptive language drew on existing lay characterizations of selfies: mirror selfies, beach selfies, and so on. They did, however, make a clear distinction between “solo” selfies, which I ended up characterizing as “me selfies,” and group selfies (“groupies”), which I adopted. They also attached great significance to whether a selfie was going to be a profile picture or not. The extra labor that goes into profile pictures informed my analysis of positioning in selfies. The third type of selfies that I felt needed to be added was that of significant other selfies. This addition allowed me to tap into a common communicative practice that I had observed in association with selfies, that of announcing or celebrating close relations with one person (e.g., best friend, mother, sibling) or indeed, a pet. This appeared to be distinctly different to group selfies (normally of four or five people). In the analysis, each of these three types of selfies proved to be linked with a different placement (e.g. me selfies were mostly placed as profile pictures), different visual arrangements of the person or people portrayed in them, different communicative purposes associated with their posting, and different types of audience engagement in them.10

Table 1 below reproduces information about the data set of the collected selfies. This includes the total number of selfies in each case, singling out me selfies that were posted as profile pictures and the average number of likes and comments that such selfies attracted. In terms of other information about the chosen users that is notable, there were around thirty nationalities involved in the list of observed users and their friends. Their nationality (or nationalities) rarely mapped with their actual locations, so I decided to note where users were located. Of the list of chosen individuals: Kate is London-based with American parents. Maria is half English, half Greek and is London-based. Saachi has Indian parents, and she, too, is based in London. Petros is half Greek, half Romanian and is based in Greece. Aris is a Greece-based Greek. The article was based on the analysis of 189 selfies from the three female selfie-posters (aged 16–17) and a total of 1,713 comments that these selfies received.

| Kate (882 Friends) | Maria (1316) | Saachi (790) | Petros (1814) | Aris (1416) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 44 total | 58 | 87 | 39 | 27 |

| 28 me selfies | 5 | 7 | 5 | 3 |

| 13 profiles | 5 | 5 | 8 (3 solo) | 2 |

| Av. 25 comments | Av. 25 comments | Av. 25 comments | Av. 25 comments | Av. 25 comments |

| 161 likes | 53 | 161 likes | 53 | 161 likes |

| 388 | 29 | 388 | 29 | 388 |

| 264 | 11 | 264 | 11 | 264 |

| 135 | 15 | 135 | 15 | 135 |

| 153 | 153 | 153 | 153 | 153 |

I showed that both the posting of selfies and the interactional engagement with them are closely linked with story-making and story-recipiency roles. I specifically documented two systematic interactional patterns of engaging with selfies which displayed alignment with the activity of posting a selfie and affiliation with the “character(s)” in the selfie: ritual appreciation and knowing participation (see subproject Sharing-Life-in-the-Moment as Small Stories: Participation, Social Relations, and Subjectivity).11 Both practices can be characterized as instances of positive story recipiency. This involves commenters’ character-based affiliation with the selfie as well as collaborative co-telling of a story, characteristic of conversational stories of shared events amongst friends12. Ritual appreciation involves positive assessments of the selfied person(s), expressed in highly conventionalized language coupled with emojis. These semiotic choices result in congruent sequences of atomized contributions, which despite not directly engaging with one another, are strikingly similar, visually and linguistically. The example in From Narrating the Self to Posting Self(ies) shows a snapshot of such ritual appreciation comments on a selfie posted by Maria as profile pic (pp. 310–11).

I argued that ritual appreciation is designed as a response to a post that is viewed and understood as an act of performance, an artful activity that invites scrutiny and appreciation of the self as character in time and place. There is a tendency for the most viewed/viewable and edited selfies, which in turn are the me selfies, normally put up as profile pictures, to create this focus of projected alignment on the “character,” the self that is put up for scrutiny. To display yourself as a sixteen-year-old young woman “in view” of potentially hundreds of your Facebook “friends” certainly evokes occasions of the catwalk and modeling, thus conforming with a microcelebrity presentation of self, a set of practices that position the audience as a fan base.13 At the same time, to view, scrutinize, and “admire” your “friend,” often a close friend offline, other times a relative stranger, as a microcelebrity on display, requires joining in (potentially many) others in a frame of spectatorship that is not part of your ordinary relationship with your friend or a stranger. This engagement is what, in my view, qualified aligned responses to selfies as “ritual,” in Collins’s terms: “a mechanism of mutually focused emotion and attention producing a momentarily shared reality, which thereby generates solidarity and symbols of group membership.”14

Knowing participation, on the other hand, creates more specific and individual alignment responses, by bringing in and displaying knowledge from offline, pre-posting activities and what I have called the backstory.15 It capitalizes on the story-making possibilities that a shared interactional history with the poster or any other prior knowledge affords, so that a contributor can produce specific alignment with a selfie post by elaborating on, amplifying, and co-authoring it.

Intertextual links amongst stories are abundant in friends’ conversations:16 a common means of creating and signaling such links is by referring more or less elliptically to stories of shared or known events and by inserting such references in the plot of new tales, as a way of bringing in new interpretative lenses on the storytelling underway. Social media processes of distribution and remixing facilities have afforded a more visual means of manipulation of a story’s plot, so as to create analogies with other (shared) stories. I have described this practice of intertextual linking of stories as rescripting: a media-enabled practice of sharing that systematically exploits primarily visual but also verbal manipulations of the taleworld of already circulated stories, so as to present the new tales as parody or satire of the originals. In my analysis, YouTube videos such as spoofs, memes, remixes, and mash-ups, were found to form typical instances of rescripting. Genealogically, they seem to remediate verbal activities of playfulness and satire found, for example, in circulars of jokes about an incident in online blogs. Using as case studies critical moment incidents related to the Greek crisis that were repeatedly shared in social media – see Projecting ideologically aligned audiences on YouTube – I examined rescripting as it occurred in the intersections between story-making and social media affordances, arguing that it can productively open up the sociolinguistic focus on resemiotizations of circulated activities in ways that take into account the story-making aspects of such activities.17 Rescripting the place of a taleworld ultimately leads to changes in a story’s emplotment, on the basis of the spatial semiotic repertoires associated with the new settings that the rescripting brings into the story. Participation frameworks were also found to be shaped by these changes, as commenters mainly engaged with the rescripted tale and telling, going along with the ostensibly “fictional” scenarios and engaging in active storytelling, that is, creating further plots on their basis. These studies show how rescripting is at the heart of networked audiences’ creative engagements with current affairs.

My blended ethnography of selfies-posting by female adolescents showed that selfies navigated competing requirements for the participants. The extra labor involved in choosing the “perfect” selfie, especially if it were meant as a profile picture, was in considerable tension with the users’ perceived pressure for sharing the moment as soon as it has happened. I observed many negotiations amongst friends about which of the selfies they had taken would be uploaded and crucially how quickly. I also witnessed the heartbreak and anger of participants about a friend posting a group selfie on the spur of the moment and without consulting with them first. At the same time, in the course of my observations, it became clear to me that the tide was turning. The number of me selfies posted by the group started dropping. There was a clear attempt to mitigate any potential charge of “narcissism” (a word repeatedly used by my participants in off-the-record-chats) attached to highly polished, Retrica-filtered selfies. The idea that they were not depicting the “true” image of somebody was becoming more and more prevalent. Me selfies started being strategically couched, hidden from immediate view in albums. Marwick’s tension between self-branding and authenticity, performing and rehearsing self at the same time as coming across as genuine and spontaneous, was becoming increasingly evident amongst my participants.18 One by one, they began to migrate their selfies onto Instagram, which they saw as a space much more appropriate for sharing glossy, edited pictures than Facebook. In my view, this shift has to be connected with the then public discourses about selfies as signs of self-obsessed, mostly female, social media users. Five years later, none of my participants would dream of going on Facebook: “it is for my mum and her friends,” they say dismissively. Selfies on Instagram have been reduced too. This small group of young women was not chosen with issues of representativeness in mind nor am I claiming that we can attempt any generalizations on its basis. That said, it is notable that the way in which their social media engagements have evolved, especially vis-à-vis their gradual distancing from selfies as narcissistic posts, and instead their endorsement of Stories, especially on Instagram, as a key post, is very much in accordance with market surveys about young people’s, especially women’s, patterns of use of different media apps and of Stories as a feature. It is also notable that teenagers post Instagram Stories four times more than any other age group (see these articles about Instagram’s demographics, and how teens seem to prefer it to both Snapchat and Facebook).19,20,21

The above shifts in patterns of use and attitudes are arguably a manifestation of the double bind and paradox that has been at the heart of the apps’ shift towards showing the moment. This consists in pressures to users for emplotting the ongoing present and the mundane aspects of everyday life (characteristic of the phase of “sharing the moment as breaking news”), on the one hand, and the pressures that visual depictions of self, held up for scrutiny and assessment, pose for making the moment (and yourself in it) look spectacular and ideal. My analysis of selfies showed that this double bind and the tensions that arose from it were discursively and interactionally managed by users by means of posting different types of selfies associated with different purposes and types of preferred audience engagement. For instance, group selfies were meant to be less polished and edited than me selfies, depicting more fun moments, and thus lowering the expectation of ritual appreciation – see Ritual appreciation and knowing participation above as a preferred response on the part of commenters.

The shift to Stories as a feature, I argue, helped users along in this delicate process of balancing the need for instantaneity and spontaneity with presenting ideal selves. More specifically, the product management PR, as analyzed in the EgoMediaStories Corpus showed that the design of Stories had taken on board the backlash from posting on Facebook “glossy, perfect lives,”22 and the moral panic about posting edited selfies as a narcissistic activity. It also appeared to have co-opted a widely circulating public discourse about the need for online self-presentation to be authentic and “real.”23 In this way, Stories seemed to be aimed at remedying an earlier emphasis on edited selves.

It was no accident then that Instagram was very keen to launch Stories as a facility for “imperfect sharing.” Kevin Systrom, Product Manager at the time, suggested that

Stories creates a place for content that’s not “good enough” for the Instagram feed, or at least is too silly to fit in amongst the art. Because everything disappears, you don’t have to be ashamed of that awkward face or stupid joke forever the way things posted to your real Instagram profile reflect on you forever. Systrom explains that “It basically solves a problem for all these people who want to take a ton of photos of an event or something in their lives, but want to manage what their profile looks like and not bomb feed, obviously, as that’s one of the no-nos on Instagram.” 24

It is clear from these statements, and the tools and affordances that Stories came with, that they were introduced as a way of sorting out overposting and perfect sharing, both closely linked in the public imaginary with the image of a self- and attention-obsessed user. Template stories offered by Instagram and how-to guides encouraged sharing everyday moments of having fun with friends, as was evident in the texts of the Ego Media Stories Corpus. Authenticity, an elusive, polysemous term in different contexts, was clearly developing associations in the rhetoric of both Snapchat and Instagram about Stories with being a creative storyteller who presents nonedited versions of “yourself” and “your” everyday moments, allowing glimpses of life behind the scenes (see more corpus results).

As we claim in the essay on Self,

authenticity has always been an issue with stories people tell about themselves. Autobiographies often raise doubts about the writer’s reliability, honesty, or egotism. Online life writing opens up an even larger space for doubt. On the one hand the medium seems to offer to share more information about a person than ever before. On the other, the possibilities for deception and distortion also seem greater than ever; especially when dealing with people you have never met. In an era so concerned over “fake news,” the sense that the selves being presented might also be fake, or have faked elements, is especially disturbing.

My corpus analysis of how Stories were introduced and launched as a distinct feature showed that the apps’ product management of them was especially preoccupied with offering users tools for constructing authenticity. Put differently, the design, promotion, and affordances of Stories seemed to coalesce in a directive to the tellers for presenting “authentic” selves. This directive could be seen as a form of pre-positioning users or, to use Jones’s and Maryns and Blommaert’s terms, a form of pre-texting.25,26 Pre-texting (cf. pre-textuality) refers to a process of setting conditions and scenarios that prompt communicators to perform specific actions at the expense of others and to attach specific evaluations to these actions. Pre-texting includes “conditions on sayability,” that is, practices, competencies, and contextual frames that make it possible for certain people to credibly engage in certain kinds of interactions.27

Directives, pre-positioning, or pre-texting, whichever term we choose to describe the phenomenon of apps prompting users to specific types of behavior and interaction, should not be viewed as determining users’ practices but as setting preferential conditions for certain actions but also constraints for others. On this basis, and in view of the directive for authenticity of stories attested in the corpus analysis, my aim was to delve more into it with a focus on users’ practices. How is this directive taken up and engaged with? To explore this in power- and hyperpopular users was, in my view, the first necessary point of entry into practices for two reasons: the style and content of influencers’ communication, including their stories, are highly emulated by ordinary users. And the apps themselves tend to evolve their features based on influencers’ practices, indeed on influencers’ resistances.28,29

The first phase of a multiphased ongoing study involved selecting two telling cases of female influencers to examine their stories. Kim Kardashian was chosen as a representative of the trajectory of migration of celebrity from a TV reality show to social media including the early adoption of technologies of the self, such as selfies.

Kim’s adoption of the format of Stories first on Snapchat and then on Instagram was a way of managing her hypervisibility and the backlash that she had faced from the prolific posting of revealing selfies. This was a case of moving from perfect sharing to imperfect sharing, very much in the spirit of the apps’ directive for Stories as a vehicle for constructing authenticity.

The second influencer chosen to be studied for their Stories on Instagram was Lele Pons (@lelepons), American-Venezuelan Instagram and YouTube celebrity, former top female Viner, with the most watched Stories, according to Instagram’s released figures.

The first phase of this ongoing study involved the collection of Stories (as multimodal data with their metadata) from these two influencers in an automatic collection period of twenty days in January 2019 (data collected by Anda Drasovean30), using Python command line tools and Instaloader. It also included using Python tools to convert the time of posting metadata into the influencers’ local time of posting. Our view was that it was very important, as part of getting a handle on practices of posting Stories, to have a sense of routine engagements in relation to the cycle of the day, which serves as the main temporally organizational unit for posting Stories, given that Stories, unless archived, disappear after twenty-four hours. The data of this first phase amounted to 406 Stories by Lele Pons and 599 stories by Kim Kardashian. Our subsequent coding of stories on NVivo12 included metadata, types of captions, language of choice in captions, interactive elements (e.g., swipe up features), format of Stories (e.g., live, photos, videos), mentions in Stories of others, etc. (see Figure 2).

We also coded Stories in terms of the type of experience they encoded, using the following main categories that had emerged from a qualitative, social semiotic analysis of the Stories.

Friends and family – stories that show or mention Lele’s friends or family.

Good morning/good night Stories – this category includes pictures and videos that contain greetings such as “Good night” or “Good morning.”

On the go – this category comprises pictures/videos from trips abroad, day trips, road trips with friends, etc.

Promotions – this thematic category contains two subcategories: self-promotion and endorsements and tutorials. The first subcategory contains pictures/videos that show the influencer in her professional capacity (e.g. dancer, singer, model), mentions her accomplishments, or announces the publication of new content on Instagram or YouTube. The second subcategory emerged from our observations that a significant number of videos/photos mention (with hashtag) collaborators (singers, dancers, make-up artists). The two subcategories are however not mutually exclusive.

Finally, we kept an open mind about a category that we called miscellaneous that could not fit into any of above four categories. We are in the process of fine-tuning and identifying subcategories, as we will be collecting more Stories. One subcategory that we have clearly identified in Lele Pons’s case is “humor” that comprises funny, goofy Stories, in the tradition of the slapstick genre of the Vines that made her famous in the first instance.

My corpus analysis brought to the fore certain mismatches between the apps’ rhetoric about Stories as a feature and the actual facilities and affordances offered for them.31 The first such mismatch involved the rhetoric of apps about Stories solving issues of overposting and being introduced as a format with more scarcity value while the design and affordances of Stories directed users to post stories frequently. Specifically, Stories are built on the basis of the algorithmic logic of timeliness (one of the key features of Instagram algorithm) and instant, live sharing despite setting out to allow users to go beyond the moment and to offer facilities for continuity of self. As the corpus analysis of keywords and key semantic domains showed, Stories are closely associated with sharing and capturing the moment, while “moment” in turn is associated with the mundane (“little moments”). This significance of liveliness and sharing the moment is evident in the frequency and practices of posting in the influencers’ Stories. Market research on Instagram Stories posted by businesses has found one to seven Stories is the optimal posting length.32

Lele Pons and Kim Kardashian fall on the top end of this posting frequency, making the most of their enormous fan base and integrating Stories into the sharing live and sharing now economy linked with pressures to keep their followers’ attention. Lele Pons adds content (mostly pictures and videos and fewer live Stories) several times a day (every two to three hours). Her Instagram Stories for one day are thus a veritable newsfeed designed to keep her followers engaged 24/7. One of the strategies she employs as a resource for multiple postings and for keeping her followers engaged is to produce countdown sequences: a breaking news format announces an upcoming event or happening with a temporal indication followed by countdown updates again with temporal markers.

The types of Stories that we found in our data (e.g., on the go, behind the scenes, good morning/good night; see categories above) are what I would call “small stories” well suited to the directive of sharing-life-in-the-moment with the algorithmically favored timeliness of postings and the quantified audience engagement.

Sharing-life-in-the-moment goes hand in hand with the users’ construction of authenticity. Stories of the moment, often about mundane events, capture “little moments,” taking us behind the scenes, constructing a sense of real-life, and inviting the viewers to be witnesses of that reality. The narrator becomes a recorder on the spot, a narrator-experiencer as opposed to a narrator that can step back and reflect on the goings-on. Life writing becomes life-casting, a transient, streaming format of showing the self in the here-and-now. An integral part of such storying is the amateur aesthetic,33 which is encouraged by Instagram’s tools and template stories, comprising minimal, simple static graphics. This amateur aesthetic suggests immediacy and lack of editing and polishing time, and so it becomes intertwined with the project of creating a sense of “authenticity.” Authenticity is intertwined with ordinariness and the construction of a sense of a level playing field for all users – ordinary, influencers, and businesses – despite the fact that metrics, at the heart of the stories’ design, actually separate and stratify them. The currency and uptake of this amateur aesthetic is of note. The Guardian, for instance, found, for their Instagram Stories, that simple static graphics and quick explainer videos outperformed their professionally produced videos.34

Stories have been introduced as a major vehicle for advertising and positioning ordinary users as “consumers,” as I show elsewhere.35 This is at odds with the directive of constructing authenticity, placing influencers in a double bind of navigating the competing demands of sharing ordinary life-in-the-moment with promoting themselves and their products. Our analysis shows that these competing demands are reconciled by blurring the lines between the self in ordinary life and the self as promoter (at least one third of the stories in our corpus are essentially advertisements). Deploying small stories well-suited to the directive of sharing-life-in-the-moment is the main life-casting modality for essentially conflating the influencers’ affective, relational sharing with their followers with promoting their products. Countdowns and behind the scenes are major vehicles especially in Lele’s case for creating this conflation. Tools that Instagram offers, on the face of it to enhance the relationality of stories, can also be mobilized for (self)-promotion. Location stickers for instance can advertise places (e.g., restaurants, shops, etc.). Mention stickers can advertise “friends” and their “products.” Hashtag stickers can proliferate the likelihood of certain types of stories and, in turn, promotional content becoming more popular than others. As we discuss in our essay on the Self, “self-presentation becomes indistinguishable from self-promotion,” “your life” and “your story” become a monetizable brand. Previous studies of female internet celebrities have suggested that even when they appear to mobilize a sense of individual agency and authenticity, they remain policed, controlled, and contained by the neoliberal and postfeminist discourses that allow them to acquire a mediatized fame in the first place.36 Such discourses essentially naturalize femininity on the female body, promoting its (hyper)visibility and display as a site of identity-making.37

This inherent contradiction of celebritization between authenticity and visual/visible display of self for scrutiny has not gone away in Stories, despite being introduced as a technology of the self that remedies the hypervisibility of selfies and the perils of perfect sharing. Stories in fact consolidate the visuality and viewability of selves, adding sophisticated metrics of audience engagement that are tied to the experience of stories as (re)viewable products. What changes though in the case of Stories is that the affordances that the relational and affective power of stories that they invoke and the affordances that they come with allow the project of constructing authenticity to exploit the conflation between attention and affection economy, in Abidin’s terms.38 Stories connect, are a prime relational communication format, but they also grab attention. They increase users’ dwell time in an app both as storytellers (we have seen how sharing-life-in-the-moment leads to frequent postings) and as audience: viewing stories takes time.

An authentic self is intimately linked with the sharing of an everyday, ordinary life that creates connections with the followers. The followers’ engagement with Stories on their smart phones is a big part of this immersive, intimate experience. Stories appear full view on their smart phones. Their viewing engagements flatten out friends and influencers, as stories appear next to one another and can be viewed one after another. A story of your close friend going out clubbing can be next to a story from an influencer, also clubbing, next to a story promoting a product. This is another case of poly-storying: a visual and experienced contiguity and coexistence that conflates the ordinary with the promotional and, as have seen, relationality and affectivity with quantification. Authenticity therefore becomes interwoven with an algorithmically mediated and configured relationship between influencer and followers, which prompts affection and connection of a ritual appreciation kind. It is notable that the Stories which include the replies to stories by followers (replies are, at the time of writing, private) are akin to the ritual appreciation comments I documented in my study of selfies. Same conventionalized, highly positive language and heart emojis affiliating with the influencer as the protagonist of their stories. A type of “love you” economy.

Reciprocation with more “love you” messages from the initial poster seems to consolidate a preference for a three-part sequence: post (in this case a story) – ritual appreciation as response – thanks and reciprocation of ritual appreciation in response to the response.

These posts are, of course, self-selected by Lele Pons, and we can speculate about the number of hate messages that she receives alongside the “love you” ones. The point however remains that interactions between followers and followed on the basis of Stories are in line with the affection economy already developed on the basis of other technologies of the self, especially selfies. For all their emphasis on authenticity, stories are presenting a strong genealogical continuity with a (micro)-celebritized display of a visual and viewable self (and life) that prompts a character-based affiliation as engagement.

Text

Middle: The social media designing of stories

Top: Sharing the moment now: Stories and lives as breaking news

RHS: Storying the moment – Stories as features

Bottom: Showing the moment: Rescripting

LHS: User practices: Narrative stancetaking

Endnotes

- Asif Agha, “Voice, Footing, Enregisterment,” Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 15, no. 1 (2005): 38–59, https://doi.org/10.1525/jlin.2005.15.1.38. ↩

- e.g., David Houghton et al., “Engaging Consumers in Facebook: The Unintended Consequences of Photograph Sharing on Personal Relationships” (Academy of Marketing Conference 2013, Cardiff, 2013), https://researchportal.hw.ac.uk/en/publications/engaging-consumers-in-facebook-the-unintended-consequences-of-pho. ↩

- e.g., Angela McRobbie, The Aftermath of Feminism: Gender, Culture and Social Change (London: Sage, 2009). ↩

- See https://twitter.com/EllenDeGeneres/status/440322224407314432 ↩

- For details on the definition of small stories, see Alexandra Georgakopoulou, Small Stories, Interaction and Identities (Amsterdam; Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 2007). ↩

- Alexandra Georgakopoulou, “Sharing as Rescripting: Place Manipulations on YouTube between Narrative and Social Media Affordances,” Discourse, Context and Media 9 (2015): 64–72, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2015.07.002. ↩

- For an overview, see Arnulf Deppermann, “Positioning,” in The Handbook of Narrative Analysis, ed. Alexandra Georgakopoulou and Anna De Fina (Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley, 2015), 369–87, https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118458204.ch19. ↩

- See section 3.1 in Alexandra Georgakopoulou, “From Narrating the Self to Posting Self(Ies): A Small Stories Approach to Selfies,” Open Linguistics 2, no. 1 (January 16, 2016), https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2016-0014. ↩

- For details of the tracking and intense observation process over a period of eighteen months and the choice of data, see Alexandra Georgakopoulou, “From Narrating the Self to Posting Self(Ies): A Small Stories Approach to Selfies,” Open Linguistics 2, no. 1 (2016), https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2016-0014. My study included elements of a blended ethnography: I navigated between observation, selection, and analysis of online material and observing and interrogating, through off-the-record-chats, practices of my daughter and her close friends’ selfie postings, social media engagements, and their real-time migration of posting selfies from Facebook to Instagram and Snapchat (these are described in detail in my Methods section). ↩

- Alexandra Georgakopoulou, “From Narrating the Self to Posting Self(Ies): A Small Stories Approach to Selfies,” Open Linguistics 2, no. 1 (2016), https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2016-0014. ↩

- See also Alexandra Georgakopoulou, “‘Friendly’ Comments: Interactional Displays of Alignment on Facebook and YouTube,” Social Media Discourse, (Dis)identifications and Diversities, December 8, 2016, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315624822-12. ↩

- Georgakopoulou, Small Stories, Interaction and Identities. ↩

- Theresa M. Senft, “Microcelebrity and the Branded Self,” in A Companion to New Media Dynamics (Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley, 2013), 346–54, https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118321607.ch22. ↩

- Randall Collins, Interaction Ritual Chains, Student ed (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2004), https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt13x0rs3. 7. ↩

- Georgakopoulou, “From Narrating the Self to Posting Self(Ies).” ↩

- Georgakopoulou, Small Stories, Interaction and Identities. ↩

- Alexandra Georgakopoulou, “Small Stories Transposition and Social Media: A Micro-Perspective on the ‘Greek Crisis,’” Discourse & Society 25, no. 4 (July 1, 2014): 519–39, https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926514536963. ↩

- Alice Marwick, Status Update: Celebrity, Publicity, and Branding in the Social Media Age (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2013). ↩

- Josh Constine, “Instagram Launches ‘Stories,’ a Snapchatty Feature for Imperfect Sharing,” TechCrunch (blog), 2016, http://social.techcrunch.com/2016/08/02/instagram-stories/. ↩

- Stacey McLachlan, “Instagram Demographics in 2023: Most Important User Stats for Marketers,” HootSuite, March 24, 2022, https://blog.hootsuite.com/instagram-demographics/. ↩

- Piper Jaffray, “Instagram Inches Ahead of Snapchat in Popularity among Teens,” CNBC, October 22, 2018, https://www.cnbc.com/2018/10/22/instagram-ahead-of-snapchat-in-popularity-among-teens-piper-jaffray.html. ↩

- Kate Gibson, “Facebook’s Biggest Problem Isn’t Privacy -- It’s Young People,” CBS News, August 29, 2018, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/facebooks-biggest-problem-isnt-privacy-its-young-people/. ↩

- Marwick, Status Update. ↩

- Constine, “Instagram Launches ‘Stories,’ a Snapchatty Feature for Imperfect Sharing.” ↩

- Corrin Jones, “The Social Engineering Techniques to Look Out For,” accessed August 30, 2019, https://www.cwps.com/blog/social-engineering-techniques-awareness. ↩

- Katrijn Maryns and Jan Blommaert, “Pretextuality and Pretextual Gaps,” Pragmatics 12, no. 1 (January 1, 2002): 11–30, https://doi.org/10.1075/prag.12.1.02mar. ↩

- Maryns and Blommaert, “Pretextuality and Pretextual Gaps.” 11. ↩

- cf., Crystal Abidin, “#familygoals: Family Influencers, Calibrated Amateurism, and Justifying Young Digital Labor,” Social Media + Society 3, no. 2 (April 1, 2017): 2056305117707191, https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305117707191. ↩

- See also Taina Bucher, If...Then: Algorithmic Power and Politics, Oxford Studies in Digital Politics (Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2018). ↩

- A. Georgakopoulou, “Designing Stories on Social Media: A Critical Small Stories Perspective on the Mismatches of Story-Curation,” Linguistics & Education, 2019, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2019.05.003. ↩

- See ResearchGate profile at https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Anda-Drasovean. ↩

- cf., Abidin, “#familygoals: Family Influencers, Calibrated Amateurism, and Justifying Young Digital Labor.” ↩

- Brian Peters, “We Analyzed 15,000 Instagram Stories from 200 of the World’s Top Brands,” Buffer, November 8, 2018, https://buffer.com/resources/instagram-stories-research. ↩

- See Jessica Davies, “The Guardian Finds Less Polished Video Works Better on Instagram Stories,” Digiday (blog), July 5, 2018, https://digiday.com/media/guardian-finds-less-polished-video-works-better-instagram/. ↩

- Georgakopoulou, “Designing Stories on Social Media: A Critical Small Stories Perspective on the Mismatches of Story-Curation.” ↩

- e.g., Jessalynn Keller, Girls’ Feminist Blogging in a Postfeminist Age (London: Routledge, 2015), https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315755632. ↩

- e.g., Rosalind Gill, Gender and the Media (Cambridge: Polity, 2007). ↩

- Abidin, “#familygoals: Family Influencers, Calibrated Amateurism, and Justifying Young Digital Labor.” ↩

Bibliography

- Abidin, Crystal. “#familygoals: Family Influencers, Calibrated Amateurism, and Justifying Young Digital Labor.” Social Media + Society 3, no. 2 (April 1, 2017): 2056305117707191. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305117707191.

- Agha, Asif. “Voice, Footing, Enregisterment.” Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 15, no. 1 (2005): 38–59. https://doi.org/10.1525/jlin.2005.15.1.38.

- Bucher, Taina. If...Then: Algorithmic Power and Politics. Oxford Studies in Digital Politics. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Collins, Randall. Interaction Ritual Chains. Student ed. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2004. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt13x0rs3.

- Constine, Josh. “Instagram Launches ‘Stories,’ a Snapchatty Feature for Imperfect Sharing.” TechCrunch (blog), 2016. http://social.techcrunch.com/2016/08/02/instagram-stories/.

- Davies, Jessica. “The Guardian Finds Less Polished Video Works Better on Instagram Stories.” Digiday (blog), July 5, 2018. https://digiday.com/media/guardian-finds-less-polished-video-works-better-instagram/.

- Deppermann, Arnulf. “Positioning.” In The Handbook of Narrative Analysis, edited by Alexandra Georgakopoulou and Anna De Fina, 369–87. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118458204.ch19.

- Georgakopoulou, Alexandra. “Small Stories Transposition and Social Media: A Micro-Perspective on the ‘Greek Crisis.’” Discourse & Society 25, no. 4 (July 1, 2014): 519–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926514536963.

- Georgakopoulou, Alexandra. Small Stories, Interaction and Identities. Amsterdam; Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 2007.

- Georgakopoulou, Alexandra. “From Narrating the Self to Posting Self(Ies): A Small Stories Approach to Selfies.” Open Linguistics 2, no. 1 (January 16, 2016). https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2016-0014.

- Georgakopoulou, A. “Designing Stories on Social Media: A Critical Small Stories Perspective on the Mismatches of Story-Curation.” Linguistics & Education, 2019. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2019.05.003.

- Georgakopoulou, Alexandra. “From Narrating the Self to Posting Self(Ies): A Small Stories Approach to Selfies.” Open Linguistics 2, no. 1 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2016-0014.

- Georgakopoulou, Alexandra. “‘Friendly’ Comments: Interactional Displays of Alignment on Facebook and YouTube.” Social Media Discourse, (Dis)identifications and Diversities, December 8, 2016. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315624822-12.

- Georgakopoulou, Alexandra. “Sharing as Rescripting: Place Manipulations on YouTube between Narrative and Social Media Affordances.” Discourse, Context and Media 9 (2015): 64–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2015.07.002.

- Georgakopoulou, Alexandra. Small Stories, Interaction and Identities. Vol. 8. Studies in Narrative. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2007. https://doi.org/10.1075/sin.8.

- Gibson, Kate. “Facebook’s Biggest Problem Isn’t Privacy -- It’s Young People.” CBS News, August 29, 2018. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/facebooks-biggest-problem-isnt-privacy-its-young-people/.

- Gill, Rosalind. Gender and the Media. Cambridge: Polity, 2007.

- Houghton, David, Adam Joinson, Nigel Caldwell, and Ben Marder. “Engaging Consumers in Facebook: The Unintended Consequences of Photograph Sharing on Personal Relationships.” Cardiff, 2013. https://researchportal.hw.ac.uk/en/publications/engaging-consumers-in-facebook-the-unintended-consequences-of-pho.

- Jaffray, Piper. “Instagram Inches Ahead of Snapchat in Popularity among Teens.” CNBC, October 22, 2018. https://www.cnbc.com/2018/10/22/instagram-ahead-of-snapchat-in-popularity-among-teens-piper-jaffray.html.

- Jones, Corrin. “The Social Engineering Techniques to Look Out For.” Accessed August 30, 2019. https://www.cwps.com/blog/social-engineering-techniques-awareness.

- Keller, Jessalynn. Girls’ Feminist Blogging in a Postfeminist Age. London: Routledge, 2015. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315755632.

- Marwick, Alice Emily. Status Update: Celebrity, Publicity, and Branding in the Social Media Age, 2013.

- Marwick, Alice. Status Update: Celebrity, Publicity, and Branding in the Social Media Age. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2013.

- Maryns, Katrijn, and Jan Blommaert. “Pretextuality and Pretextual Gaps.” Pragmatics 12, no. 1 (January 1, 2002): 11–30. https://doi.org/10.1075/prag.12.1.02mar.

- McLachlan, Stacey. “Instagram Demographics in 2023: Most Important User Stats for Marketers.” HootSuite, March 24, 2022. https://blog.hootsuite.com/instagram-demographics/.

- McRobbie, Angela. The Aftermath of Feminism: Gender, Culture and Social Change. London: Sage, 2009.

- Peters, Brian. “We Analyzed 15,000 Instagram Stories from 200 of the World’s Top Brands.” Buffer, November 8, 2018. https://buffer.com/resources/instagram-stories-research.

- Senft, Theresa M. “Microcelebrity and the Branded Self.” In A Companion to New Media Dynamics, 346–54. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118321607.ch22.