Health Quantification and Self-Tracking

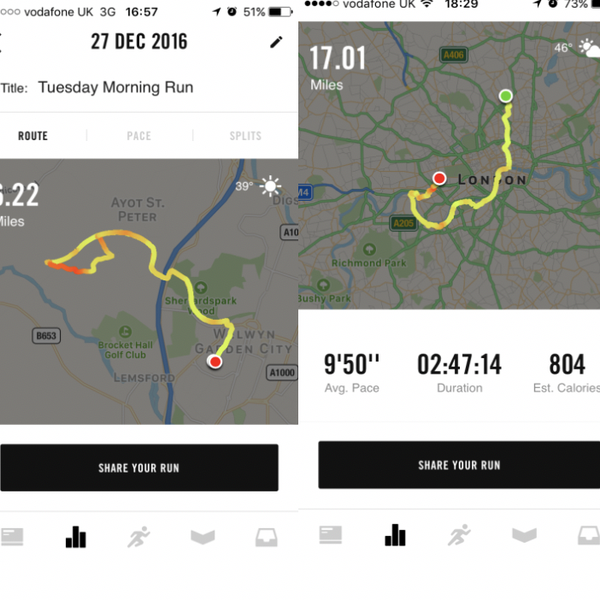

Health quantification involves the reliance upon science and the technological extensions and affordances of digital health sensors and devices in the monitoring of the self and individual health. Self-tracking technologies and social media platforms combine to enable a variety of ways to represent “health.” This research explores the use of digital health technologies and social media sharing as forms and modes of self-tracking and self-quantification.

Identity is our mystery. We have no idea who we are – what humans are, and what humans are good for. [...] Self-tracking and the Quantified Self movement are contemporary probes into this mystery, part of our feeble attempt to figure out who we are – as individuals and a collective.1

Participants of the quantified self (QS) movement, through consumer devices, monitor everything that can be put into data to improve and optimize individual health. Gary Wolf, co-founder of the movement (with Kevin Kelly) has called it “self-knowledge through numbers.”2 The quantified self movement came from a California-based laboratory, which now has an international collaboration of users and makers of self-training tools.3 Swan understands self-quantification as “contemporary formalisations belonging to the general progression in human history of using measurement, science, and technology to bring order, understanding, manipulation, and control to the natural world, including the human body.”4 Swan argues that the quantified self movement is inherently a Big Data problem, in terms of collection, processing, and analysis.5 This movement, or rather its practices of capturing data, can now broadly be described as self-tracking: the process of tracking aspects of our bodies and our minds, which promotes “an exploratory worldview in which the key goal is learning through the process of data collection and interpretation.”6 This perspective takes a particularly techno-utopian angle, similarly to Nafus and Sherman,7 who suggest that self-quantification could be considered as an alternative to Big Data practices, since self-management could be considered emancipatory when compared to the perspective of wider state surveillance. Digital health practices and the affordances of self-tracking devices and social media have dimensions of both self-surveillance and wider surveillance. Robins and Webster argue that such types of “social control [have become] more pervasive, more invasive, more total, but also more routine, mundane and inescapable.”8 Therefore, such self-surveillance may in fact be normalized, even desired as a way of proving individual responsibility within neoliberal advocated citizenship practices and behaviors: “these surveillant assemblages are ideally configured voluntarily, as lay people judge their participation in self-surveillance as being in their own best interests.”9 Self-tracking therefore, ensures that the body and health are “being subjected to regimes of knowledge production and data-driven modes of bio-power.”10 These regimes of bio-power and neoliberal judgment dictate which is and what are not healthy, productive, and self-bettering behaviors, subsumed through discourses of competition and comparison.11

For Fet, a keen cyclist who tracked his daily work commute, health was quantifiable through metrics, and being healthy was determined by his body weight:

Mine is a number, and my number is 65kg, and if I’m above 65kg I consider myself as “unhealthy.” For me I could be 66kg or I could be 80kg. I’d still consider myself as unhealthy. There’s no difference: as long as I go above that benchmark. I know I’m eating well, yeah. I have the odd kebab or Chinese on the weekend but in general during the week I eat well. I would consider myself a healthy eater. When it comes to health overall … if I’m above 65kg, which I’ve set myself, I don’t know why or how, I think mainly because that’s my weight roughly, for the past 10 years because I haven’t really changed in terms of my weight, so if I go above that mark by 1kg or 10kg I’m unhealthy. (Fet, First Interview, 30, M)

Fet “set” and determined his “health” by numerical weight. His reasoning was interestingly unclear to him. However, the use of numbers to determine his healthiness was considered in regard to the consistency of being approximately a certain weight over a ten-year period. Interestingly, his rationale for determining whether he was “unhealthy” or not was related to being above this set weight of 65kg, regardless of the relative increase in metrics. For example, being 75kg or 100kg was not a determinant of degrees of unhealthiness. Quite simply, for Fet, weighing over 65kg had a causal relationship with being unhealthy. Therefore, the physical deterioration of health was understood through numerical weight gain, regardless of other mental or physical factors such as illness, disease, lack of nutrition, or exercise (in his case, cycling). Fet’s perspective resonated with Purpura et al.’s argument concerning and recognition of the “idea that sensors accurately measure attributes that directly translate to health; that health can be measured [works] in a purely reductive way.”12 Another interesting aspect of this response is the metricized interpretation of being a “healthy eater,” which Fet related to eating well five days per week, with unhealthy foods (such as takeaways) consumed only on the weekend.

I’m not a gym freak, never actually set foot in a gym and I’m not obsessive about keeping healthy, mainly because I’m lucky my metabolism is pretty quick and I’ve always been roughly the same weight, but saying that I have a weight goal, to not go over, because in my mind if I go over that I would feel unhealthy that goal is 65kg. (Fet, Final Interview, 30, M)

For Fet, being healthy was being his goal weight. Quantifying his health in this way arguably meant that Fet did not have to take into consideration the self-regulation of many other lifestyle factors, which could impact on healthiness (such as exercise). By relying on this simplified quantification system, Fet understood his health through numbers in line with the discourse advocated by the self-quantification community and its founders, Gary Wolf and Kevin Kelly. This approach advocates “self-knowledge by numbers.”13 These reductive approaches to understanding and managing health reflect how the participants’ interpretations of what determines good health or ill health is strongly encoded by their own technological, medical, and cultural assumptions, which creates categories of importance.14 A number of questions can therefore be asked: What data do we collect and why? How does this reflect cultural, technological, and medical assumptions and discourses concerning what is healthy or unhealthy?

Foucault’s theorizing of “technologies of the self,”15 which permit “individuals to effect by their own means or with the help of others a certain number of operations on their own bodies and souls, thoughts, conduct, and way of being, so as to transform themselves in order to attain a certain state of happiness, purity, wisdom, perfection, or immortality” uncovers how neoliberal self-managing discourses are advocated and enabled. Consumer health movements have developed alongside the discursive prioritizing and management of individual healthcare; this has shifted the dominant public health discourse of medical hegemony, which refers to the medical profession’s control over health knowledge, health practices, and healthcare, towards a discourse of “‘medicalisation,’ which is the term used to describe the apparent encroachment of medicine upon a growing number of spheres of everyday life.”16

Similarly, practices of “medicalisation,” enabled through the diagnostic speculation of gathering (mis)information online, and the adoption of consumer devices and applications, enable users to gaze inward. These practices are attempts to understand what goes on inside our bodies and to monitor individual capacities through capturing self-tracking information and data, which changes and molds health-related behaviors and activities. This research conceptualizes health-optimization as a neoliberal rationality discursively embedded within consumer and state health movements promoting continual self-improvement of health as the core ambition of the human being and human body.

Self-surveillance can be understood as a surveying practice of the self and in relation to this thesis, of one’s own body, health, fitness, and lifestyle choices. Self-surveillance therefore can be understood as a reflexive practice of the self, as we examined through Giddens’s theorizing of postmodern practices of reflexivity in understanding self-identity.17 Self-surveillance then cannot be removed from the participants’ perceptions and constructions of self-identity; it is an interrelated, interdependent, and co-evolving process. The more the participants’ felt they learned from being reflexive in relation to their health and fitness practices, the more self-surveying they became. Reflexivity therefore, differs from self-surveillance, and, in accordance with Giddens’s theorizing, it impacts directly upon personal behaviors. The participants’ reflexive practices were aided by the methodologies, particularly the process of reflexive diarizing on individual behaviors and the interviews to contextualize these practices within a broader socioeconomic, cultural, and political perspective. Self-surveillance therefore, differs from reflexivity in that it does not always impact upon behavior, but rather situates itself as a purposeful observation and monitoring of the self.

Self-trackers do not always outline a specific goal but are curious about the information implicated in the numbers themselves.18 Therefore, as Langwieser and Kirig argue: “the rules of our knowledge-based meritocracy invite to this self-optimisation: Who wants to be healthy, happy and successful, needs to become a self-designer.”19 This has arguably contributed to an ideological shift within society, from viewing the individual as a “passive” consumer, to viewing them as an “active” consumer of “health.”20 As Lara asserted:

I’ve always just wanted to be the best version I can be so I’m always looking at what I can do, it’s always been kind of drummed in, I don’t know where it’s come from but there’s always, what can I do better, or what could I have done differently. (Lara, Final Interview, 28, F)

Lara usefully articulates the overarching theme of this chapter, and arguably the entire thesis, in relation to being the best version of oneself or to continually improve in regard to health and fitness. Yet, the participants frequently recognized that they did not know why they felt this way. Preventing ill health, disease, or death was surprisingly never identified or discussed as a reason for managing and improving health. van Dijck identifies the function of these technologies as translating “relationships between people, ideas, and things into algorithms in order to engineer and steer performance.”21 The discourses that surround health self-care, and individualized and privatized health practices, advocated by the state and lifestyle health and wellness apps, assume that people have the power to choose healthy or unhealthy lifestyles. This is reflected in various discourses of self-betterment and continual self-improvement, which were dominant throughout the research findings:

If you go to a gym everybody is there for self-improvement so that’s a better place to train. (Roy, Final Interview, 26, M)

The participants identified self-improvement as an inherent motivator for individuals to exercise or prioritize health and fitness-related activities and consumption. This was not always to reach specific goals:

I believe that my current health is good; I am in good shape so therefore calorie counting and losing weight is not my priority. I am more focused on speed and being in a better shape. (Fet, Diary Entry, 30, M)

At times, the participants were ambiguous and nondefinitive about what self-improvement meant for them. Rather, they simply articulated that the goal was self-betterment. Based on the belief that the more we understand ourselves through “technologies of the self,” the more we can improve ourselves, this discourse translates ideas of identification of the self into the prevention or cure of health issues, which can provide an “economy of hope.”22 These political and promissory economies of hope present the logics of optimization and improvement as an attainable goal and form of control through personal diagnosis, self-tracking, and the “hopeful” prevention of pathologies.23 Arguably, this could be understood as manifesting itself in the proliferation of the “worried well,” whereby the continual monitoring and capturing of data about the body through self-tracking devices and associated practices stokes unneeded anxiety in those who are healthy.24 In this regard, the worried well self-trigger such health anxieties through an overexamination of the body and health via these technologies.25 Thus, what manifests itself is a drive to continually optimize and improve health to feel productive, proactive, and therefore, healthy, thus enacting care of the self and responsible citizenship practices:26

I like improvement and seeing things getting better, not necessarily getting to the best in that thing but to get to see the progression in myself. Like, that’s where I started and either that’s what I can do or that’s what I couldn’t do and then to work for it, put in hard work and the rewards of it are purely in my own mind and body. It’s not for any other kind of greater gain, not to look better or for anyone’s opinions of me to be any different. It’s just that I feel really good that I’ve started somewhere. I worked hard, I looked into stuff and I improved. That’s the main gain for me. (Tim, Final Interview, 35, M)

Self-identifying is therefore achieved through self-transformation, and life-strategizing technologies of the self to compete within a community, which is further encouraged through self-tracking applications and practices.27 Tim and many of the participants used their devices and social media as tools not simply to listen to, read, or watch, but as platforms to speak to others.28 The participants were the narrators, and the technologies were the narratees, the audience for their words or their data:29

Also, to show that even feeling pretty rough from the night before that exercise was possible and that it made me feel good. I also use Instagram and Facebook to look back and see where I was physically and mentally at certain times so this will show me in the future how I've improved since then and how I was feeling at that time. (Tim, Diary Entry, 34, M)

Being on a self-betterment journey to achieve better health and individual skill development was a dominant discourse in all the participants’ diary entries and final interviews, in which the platform enabled the space to look back and forward:

I still want to keep pushing myself as best I can with regards to the fitness thing. I’ve still got goals I want to achieve before it’s physically impossible for me to achieve them. It’s always going to be a part of my life I think. (Matt, Final Interview, 41, M)

Surveillance of the body, health, and fitness through these digital health technologies in this research is understood as “self-tracking practices [that] are directed at regularly monitoring and recording, and often measuring elements of an individual’s behaviours or bodily functions.”30 Human beings’ desire to reflexively monitor aspects of our lives is not new, for example, keeping diaries.31 What makes self-tracking new in the context of this research is its digitization and subsequent engagement with performativity on social media. Identity formation enabled through self-representation and online communication practices are increasingly mediated and reformed through digital modes enabled by this “paradigm of mobility”32, the participatory and sharing affordances of Web 2.0, and in particular social media and online communities. Through the sharing of self-tracking data on social media, self-monitoring of the body is extended into the communities’ gaze.

Endnotes

- Kevin Kelly, “Self-Tracking? You Will,” The Technium, March 25, 2011, www.kk.org/thetechnium/archives/2011/03/self-tracking_y.php. ↩

- G. Wolf, “The Data-Driven Life,” New York Times, April 28, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/02/magazine/02self-measurement-t.html?_r=3&ref=magazine&pagewanted=al l. ↩

- M. Swan, “Emerging Patient-Driven Health Care Models: An Examination of Health Social Networks, Consumer Personalized Medicine and Quantified Self-Tracking,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 6, no. 2 (2009): 492–525. ↩

- M. Swan, “The Quantified Self: Fundamental Disruption in Big Data Science and Biological Discovery,” Big Data 1, no. 2 (2013): 85–99. 86. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- J. Fajans, “Self-Experimentation and the Quantified Self: New Avenues for Positive Psychology Research and Application” (Claremont Graduate University, 2013), https://www.slideshare.net/fitnessSD/self-experimentation-the-quantified-self-new-avenues-for-positive-psychology-research-and-application. ↩

- D. Nafus and J. Sherman, “This One Does Not Go up to 11: The Quantified Self Movement as an Alternative Big Data Practice,” International Journal of Communication 8 (2014): 1784–94. ↩

- K. Robins and F. Webster, Times of the Technoculture: From the Information Society to the Virtual Life (London: Routledge, 1999). 180. ↩

- Deborah Lupton, “The Digitally Engaged Patient: Self-Monitoring and Self-Care in the Digital Health Era,” Social Theory and Health 11 (2013): 256–70. 12. ↩

- Btihaj Ajana, “Digital Health and the Biopolitics of the Quantified Self,” Digital Health, January 2017, https://doi.org/10.1177/2055207616689509. 2. ↩

- William Davies, The Limits of Neoliberalism: Authority, Sovereignty and the Logic of Competition (London: Sage, 2015). ↩

- Stephen Purpura et al., “Fit4Life: The Design of a Persuasive Technology Promoting Healthy Behavior and Ideal Weight,” Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, May 7, 2011, 423–32, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1145/1978942.1979003. 6. ↩

- Wolf, “The Data-Driven Life.” ↩

- Rebecca Roach, “Epilepsy, Digital Technology and the Black-Boxed Self,” New Media and Society 20, no. 8 (August 1, 2018): 2880–97, https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817736926. ↩

- M. Foucault, “Technologies of the Self,” in Technologies of the Self: A Seminar With Michel Foucault, ed. L. H. Martin, H. Gutman, and P. H. Hutton (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1988), 16–49. 18. ↩

- Deborah Lupton, “Foucault and the Medicalisation Critique,” in Foucault, Health and Medicine, ed. A. Petersen and R. Bunton (London: Routledge, 1997), 94–110. 95. ↩

- Anthony Giddens, Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1991). ↩

- Wolf, “The Data-Driven Life.” ↩

- C. Langwieser and A. Kirig, Konsument (Kelkheim: Zukunftsinstitut, 2010). 105. ↩

- J. Q. Tritter, “Revolution or Evolution: The Challenges of Conceptualizing Patient and Public Involvement in a Consumerist World,” Health Expectations 12, no. 3 (2009): 275–87. ↩

- José Van Dijck, “‘You Have One Identity’: Performing the Self on Facebook and LinkedIn,” Media, Culture and Society 35, no. 2 (2013): 199–215, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443712468605. 202. ↩

- C. Novas, “The Political Economy of Hope: Patients’ Organizations, Science and Biovalue,” BioSocieties 1, no. 3 (2006): 289–305. 289. ↩

- Nikolas Rose, The Politics of Life Itself: Biomedicine, Power and Subjectivity in the Twenty-First Century (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2007). ↩

- I. Husain and D. Spence, “Can Healthy People Benefit from Health Apps?,” British Medical Journal 350:h1887 (2015), https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h1887. 2. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Nikolas Rose, Powers of Freedom: Reframing Political Thought (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999). ↩

- Anthony Elliott and John Urry, Mobile Lives (Abingdon: Routledge, 2010). ↩

- Jill Walker Rettberg, Seeing Ourselves Through Technology (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137476661. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Deborah Lupton, The Quantified Self (Cambridge: Polity, 2016). 2. ↩

- Jill Walker Rettberg, Seeing Ourselves Through Technology (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137476661. ↩

- Elliott and Urry, Mobile Lives. 7. ↩

Bibliography

- Ajana, Btihaj. “Digital Health and the Biopolitics of the Quantified Self.” Digital Health, January 2017. https://doi.org/10.1177/2055207616689509.

- Davies, William. The Limits of Neoliberalism: Authority, Sovereignty and the Logic of Competition. London: Sage, 2015.

- Elliott, Anthony, and John Urry. Mobile Lives. Abingdon: Routledge, 2010.

- Fajans, J. “Self-Experimentation and the Quantified Self: New Avenues for Positive Psychology Research and Application.” Claremont Graduate University, 2013. https://www.slideshare.net/fitnessSD/self-experimentation-the-quantified-self-new-avenues-for-positive-psychology-research-and-application.

- Foucault, M. “Technologies of the Self.” In Technologies of the Self: A Seminar With Michel Foucault, edited by L. H. Martin, H. Gutman, and P. H. Hutton, 16–49. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1988.

- Giddens, Anthony. Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1991.

- Husain, I., and D. Spence. “Can Healthy People Benefit from Health Apps?” British Medical Journal 350:h1887 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h1887.

- Kelly, Kevin. “Self-Tracking? You Will.” The Technium, March 25, 2011. www.kk.org/thetechnium/archives/2011/03/self-tracking_y.php.

- Langwieser, C., and A. Kirig. Konsument. Kelkheim: Zukunftsinstitut, 2010.

- Lupton, Deborah. “Foucault and the Medicalisation Critique.” In Foucault, Health and Medicine, edited by A. Petersen and R. Bunton, 94–110. London: Routledge, 1997.

- Lupton, Deborah. “The Digitally Engaged Patient: Self-Monitoring and Self-Care in the Digital Health Era.” Social Theory and Health 11 (2013): 256–70.

- Lupton, Deborah. The Quantified Self. Cambridge: Polity, 2016.

- Nafus, D., and J. Sherman. “This One Does Not Go up to 11: The Quantified Self Movement as an Alternative Big Data Practice.” International Journal of Communication 8 (2014): 1784–94.

- Novas, C. “The Political Economy of Hope: Patients’ Organizations, Science and Biovalue.” BioSocieties 1, no. 3 (2006): 289–305.

- Purpura, Stephen, Victoria Schwanda, Kaiton Williams, William Stubler, and Phoebe Sengers. “Fit4Life: The Design of a Persuasive Technology Promoting Healthy Behavior and Ideal Weight.” Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, May 7, 2011, 423–32. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1145/1978942.1979003.

- Rettberg, Jill Walker. Seeing Ourselves Through Technology. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137476661.

- Roach, Rebecca. “Epilepsy, Digital Technology and the Black-Boxed Self.” New Media and Society 20, no. 8 (August 1, 2018): 2880–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817736926.

- Robins, K., and F. Webster. Times of the Technoculture: From the Information Society to the Virtual Life. London: Routledge, 1999.

- Rose, Nikolas. The Politics of Life Itself: Biomedicine, Power and Subjectivity in the Twenty-First Century. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2007.

- Rose, Nikolas. Powers of Freedom: Reframing Political Thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- Swan, M. “Emerging Patient-Driven Health Care Models: An Examination of Health Social Networks, Consumer Personalized Medicine and Quantified Self-Tracking.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 6, no. 2 (2009): 492–525.

- Swan, M. “The Quantified Self: Fundamental Disruption in Big Data Science and Biological Discovery.” Big Data 1, no. 2 (2013): 85–99.

- Tritter, J. Q. “Revolution or Evolution: The Challenges of Conceptualizing Patient and Public Involvement in a Consumerist World.” Health Expectations 12, no. 3 (2009): 275–87.

- Van Dijck, José. “‘You Have One Identity’: Performing the Self on Facebook and LinkedIn.” Media, Culture and Society 35, no. 2 (2013): 199–215. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443712468605.

- Wolf, G. “The Data-Driven Life.” New York Times, April 28, 2010. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/02/magazine/02self-measurement-t.html?_r=3&ref=magazine&pagewanted=al l.