Social Media and Community Surveillance

Community surveillance plays an integral role in the processes of participants’ own self-surveillance (comparing themselves to others), as well as how their communities online may perceive them (imagined surveillance), and their feedback on content is shared, reinforcing participants’ sense of self. Once “health”-related content is shared for users, “health”-related experiences shift, individually and through the gaze of others watching in social media communities.

This research explores participants’ motivations for sharing health and fitness-related content on social media (Facebook and Instagram) and the influence of community surveillance and feedback. This comes in the form of self-tracking data from applications (for example Nike+ or Strava), devices (for example, Fitbit or Garmin Watch), gym or fitness selfies, or more general “healthy” self-representations such as food photography. Within these sharing communities the self can be monitored by others. This chapter will explore and challenge the discourses that surround community practices on social media, including considerations of voyeurism, sharing, and connectivity1 in relation to sharing health behaviors and constructions of health identity. Self-surveillance or “imposed self-tracking”2 and “participatory surveillance”3, or community surveillance, ensure that “users are actively engaged in surveillance themselves as watchers, but they also participate voluntarily and consciously in the role [of being] watched.”4 Therefore, community surveillance usually comes in the form of participation and feedback on posts, and frequently ensures that the participants’ representations of their health become collaborative, as well as comparative and competitive within these sharing cultures.

This research also examines participants’ use of self-tracking and social media platforms as ethnographic sites, enabling a critical analysis of subjects’ self-representations. Using social media “requires a critical approach to context creation … participation in social networking entails both the production of one’s own self-representation and the acceptance that one may be represented by others.”5 This research therefore, defines and conceptualizes social media platforms, in particular Facebook and Instagram, as performative spheres for the construction of identity, including the social, cultural, and psychological aspects of behavior, through communication technologies.6

These ethnographic sites and this empirical analysis enable interrogation of the online representations, offline realities, and lived experiences of these individuals. However, it must be highlighted that the ethnography does not attend to analysis of these platforms (Facebook and Instagram) of self-representation themselves. Rather, the focus centers on the participants’ use of, and engagement with, them for their own representational and surveillant needs. The online data captured (screenshots) were supplied by the participants from their self-tracked or health-related content shared on Facebook and Instagram. As Kristensen and Ruckenstein argue: “These collaborations … mediate and modify human presence and perception, behaviour and decision making,” enabling participants to generate new ways of seeing themselves through such self-representational performances on social media. This further shapes “self-understanding and self-expression, suggesting a vision of technology that in its concrete materiality influences not only selves, bodies and socialities but also communication and learning.”7 So this critical analysis explores how these technologies mediate participants’ perceptions of themselves and their personal actions.

During the research period, all the participants acknowledged that being perceived as “healthy” and “active” by the social media community is incredibly important to their sense of self and health identity. Community members feeding back positively to participants’ posts in the form of likes and written affirmations made them feel proud, not only about their own practices and sharing, but also about their ability to inspire others. Seeing other online friends’ posts encouraged them to look forward to offline interactions and sociality. As Roy wrote:

It’s quite habitual to use if I check it. I’m going to Berlin in April with a lot of people I follow on IG [Instagram], so every time I see a post by one of them, I look forward to it more. (Roy, Diary Entry, 26, M)

Roy is a part of a Facebook group and community of hand-balancers and weightlifters. The members of this community mostly document their progress through posting photos and videos on their Facebook group and having (offline) meets every few months. For Roy and the other participants who are members of fitness communities, seeing other community members posting certain developments encourages them to similarly want to develop their own skills. It also adds to feelings of community, communal development, and personal skill. If one member is advancing well, Roy highlighted that he would particularly look forward to meeting this individual to train and develop their skills together. The connection between community and the understanding of others doing similar practices provided comfort and can be seen as a supportive tool in this motivating discourse of self-betterment. Sophie similarly reiterated this discourse:

It encourages me to be healthier the more I post. (Sophie, First Interview, 31, F)

In response to such community surveillance, a reflexive process ensues. The more the user self-tracks, shares, and reflects on these practices with the community, the more healthy they feel. The process of reflexivity is a motivating and guiding tool to maintain healthy practices. Lifestyle is strategically managed through the reflexive practices of the self.8 Most of the participants acknowledged community support on social media as a key motivator to share and be accountable for their fitness or health goals.

Surveillance regulated the participants’ actions towards certain norms.9 For the participants, a key motivation for sharing their health and fitness on social media was to be accountable to the community. Furthermore, this practice of being accountable to others became a common and normalized process. Accountability therefore, was conceptualized and defined as a form of self-regulation, which encouraged them to then be answerable to the wider social media community, as well as their offline networks. The participants engaged with this through conversations with peers (both online and offline), as well as through community surveillance. The action of sharing their health-related practices and behaviors over time became a normalized process of being culpable to those viewing and at times awaiting certain content. Even from their very first posts, the social media community were considered as an audience to perform for, particularly for those training towards specific goals. As Lara attested:

I’m going to be doing a 10km run in June so I shared something to keep me accountable for it and I got really great feedback from people … I think if you keep it inside, then if you don’t do it, then you’ve only got yourself that you’ve let down and you can kind of ignore it, but if you tell somebody then it kind of puts it out into the world and other people are going to ask and you have to have an answer. (Lara, First Interview, 28, F)

The consideration that a community may be watching made these participants want to document and then share their practices, exercises, and goals.10 The participants’ self-surveillance of their own behaviors and training was a fundamental practice in scrutinizing their bodies and identifying personal good or poor health. Self-surveillance to motivate the meeting of set goals is enabled through curating self-representations online. As Annie wrote:

I do get the guilty feeling if I go “off-track” – luckily today was not one of those days and so I felt pride in my fitness actions. Sharing my journey with people can in turn inspire me to keep going and better myself. We hit the gym hard today, we ate well, and we had fun! (Annie, Diary Entry, 28, F)

This can be understood as participants’ “inverting the panoptic gaze.”11 For when health-related activities are shared on social media, this inward gaze at one’s own lifestyle or exercise routine becomes a performance for the community’s consumption and surveillance. As Lou explained:

Partly, posting is a confirmation that I’m training. I want people to check in and be aware that I’m running and call me out if I’m not. Posting runs is a way of doing that without constantly talking about running. (Lou, Diary Entry, 29, F)

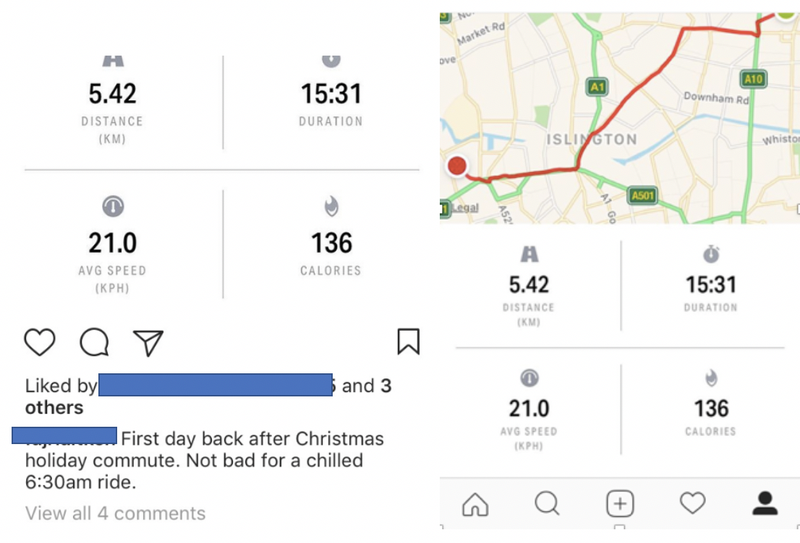

In Lou’s extract, maintaining accountability to oneself and to the community is considered a productive habit in achieving fitness goals. The participants’ “watchful vigilance,” which Mann conceptualizes as “sous-veillance,”12 is extended from the individual sphere and is captured as a performative act to be viewed by the community online. Posting proves they are doing physical exercise without having to explicitly discuss it, as Lou suggested. All of the participants recognized the motivating role of accountability once content was shared and a simultaneous accountability towards the online community, vis-à-vis oneself. Additionally, sharing self-tracking data or exercise updates provides the participants with a visual documentation and marker to keep themselves accountable to set goals. For example, Fet tracks his daily cycling commute to work:

I feel good that I have shared the post on Instagram … as a marker for myself to aim at as it is the first day back commuting after a break. (Fet, Diary Entry, 30, M)

The participants acknowledged this desire to post on social media and to track their development after a self-proclaimed indulgent Christmas break. Sharing content post-holiday became a significant signpost for letting the social media community know that they were returning back to their routine and healthy behaviors.

Motivations for sharing health and fitness-related posts on social media center not solely around direct accountability to the community. Whilst being accountable to others was a key driver, a desire for interaction with the community extended into craving support. The participants conceptualized community support in terms of written feedback on posts, private messages on Facebook and Instagram, likes on posts, and private messages sent via text or WhatsApp, for example, in relation to their shared content. This became particularly important for the participants who felt that they were not receiving support from the people close to them in their private lives. As Lara discussed when she decided to do a marathon for the first time:

Maybe it’s because it’s not enough just me, maybe it’s a confidence thing, I think. Looking outside for some reaffirmation … You want your immediate circle to have self-belief and everyone says how hard it is and it was like that’s not very positive. (Lara, Final Interview, 28, F)

Lara felt her network (offline), and particularly those who did not have similar fitness ambitions, were not supportive of her marathon goals because they either could not relate to achieving anything comparable or were simply uninterested. Lara held a personal drive to want to hit certain fitness targets. Yet, her self-belief was low, which led to feelings of anxiety that set goals were unachievable. Therefore, sharing this content can be considered a technique for understanding more about the self through these technologies. This reflects arguments that technologies of the self13 provide “new intimacies of surveillance”14 for users and viewers, enabling self-exploration and self-discovery.15

The participants felt a need to gain recognition outside of their (offline) social circle, especially when those peers were not encouraging of their goals. As Lara articulated:

Maybe that’s why I shared it, to get recognition somewhere. I don’t think of it like that, but I’m curious if I’d have been as sharing if he [Lara’s boyfriend] was more interested or gave more encouragement. (Lara, Diary Entry, 29, F)

If acknowledgment is not received from the user’s peers (offline), family, or partner, sharing online is often a way to gain recognition and guidance and compensate for a lack of support. By posting about their fitness goals on social media, the participants hoped to receive community support, encouragement, and even admiration, in the form of likes on posts or positive written feedback. This became particularly important when participants were having challenges in other areas of their lives, such as personal relationships. As Lara expanded:

I think sometimes I share to feel better about other parts of what’s going on. I wasn’t going to share anything, but my boyfriend and I had fought the night before … I think in a weird way sometimes the gratification you get from social media can make you feel better about other parts [of your life]. I realise this contradicts what I said before about not relying on the affirmation from other people. It’s a strange line I cross over back and forth in my mind sometimes. (Lara, Diary Entry, 28, F)

As Lara identifies here, and as many of the other participants reflected (in their diaries and interviews), their social media practices sometimes contradicted how they initially perceived their personal sharing. To be more specific, over time and through inevitable changing personal and private circumstances, sharing practices and in turn expectations of the communities’ roles in their individuals lives, similarly evolved based upon individual needs. In this instance, Lara had fought with her boyfriend, did not feel he was supportive of her marathon ambition, and thus she relied upon the social media community to gain support and recognition, and to boost her low self-esteem and health anxiety surrounding the marathon being potentially unachievable for her. This manifested itself in the participants’ craving support from an online community, which was a common desire for participants who did not know anyone who engaged in similar fitness practices to their own. For example, individuals taking part in unusual exercise or fitness regimes, such as Roy, a “hand-balancer” (defined in his own terms as “the performance of acrobatic body shape changing movements, or stationary poses, or both, while balanced on and supported entirely by one’s hands or arms.” (First Interview):

[I am] definitely an individual looking for a community online. All my hand-balancer friends are online. (Roy, Final Interview, 26, M)

Roy did not know any hand-balancers in his offline world and so sought out a community online to make friends and track development together through social media. Sophie similarly expressed the importance of gaining support from individuals or community members who were also marathon training:

I mentioned to a few friends that I had been for my first proper run since the London Marathon and said how I was in a lot of knee pain after. I felt proud that I had been able to push through the pain to reach my target of 5 miles. Apart from one friend who is really into their fitness and empathised with my knee pain, no one seemed too concerned, but I understand that people who don’t run/exercise regularly don’t always fully understand the frustration of an injury. (Sophie, Diary Entry, 31, F)

For Sophie, the empathy she received from a running friend, who similarly understood the hindrances of an injury, added to her sense of pride on completing the run. A common theme in all the participants’ accounts was that taking part in individualized exercise enabled them to seek out sociality and support through sharing their experiences with their online community on Facebook and Instagram. Therefore, any isolation participants experienced either in their daily lives or whilst exercising could be mediated and mitigated by sharing their practices through technology.16,17,18 Particularly when suffering from ill health or injury, catching up online frequently became an extension of community and sociality.

Endnotes

- A. M. Townsend, “SMART CITIES: Big Data, Civic Hackers, and the Quest for a New Utopia,” Stanford Social Innovation Review, 2013, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.48558/BXTE-BQ78. ↩

- Deborah Lupton, The Quantified Self (Cambridge: Polity, 2016). 103. ↩

- A. Albrechtslund, “Online Social Networking as Participatory Surveillance,” First Monday 13, no. 3 (2008), https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v13i3.2142. 310. ↩

- M. Galič, T. Timan, and B. J. Koops, “Deleuze and Beyond: An Overview of Surveillance Theories from the Panopticon to Participation,” Philosophy and Technology 30, no. 1 (2016): 9–37, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-016-0219-1. 29. ↩

- Nancy Thumin, Self-Representation and Digital Culture (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012). 149. ↩

- A. Jakala and E. Berki, “Exploring the Principles of Individual and Group Identity in Virtual Communities,” IADIS International Conference Web Based Communities, n.d., 19–26, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267794585_EXPLORING_THE_PRINCIPLES_OF_INDIVIDUAL_AND_GROUP_IDENTITY_IN_VIRTUAL_COMMUNITIES. ↩

- B. D. Kristensen and M. Ruckenstein, “Co-Evolving with Self-Tracking Technologies,” New Media and Society 5, no. 3 (2018): 219–38. 2. ↩

- Anthony Giddens, Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1991). ↩

- Phoebe Moore and Andrew Robinson, “The Quantified Self: What Counts in the Neoliberal Workplace,” New Media and Society 18, no. 11 (2016): 2774–92. ↩

- Sue Ziebland and Sally Wyke, “Health and Illness in a Connected World: How Might Sharing Experiences on the Internet Affect People’s Health?,” Milbank Quarterly 90, no. 2 (2012): 219–49, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2012.00662.x. ↩

- Deborah Lupton, The Quantified Self (Cambridge: Polity, 2016). 236. ↩

- T. Mann, D. de Ridder, and K. Fujita, “Self-Regulation of Health Behavior: Social Psychological Approaches to Goal Setting and Goal Striving,” Health Psychology 32, no. 5 (2013): 487–98, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028533. 1. ↩

- M. Foucault, “Technologies of the Self,” in Technologies of the Self: A Seminar With Michel Foucault, ed. L. H. Martin, H. Gutman, and P. H. Hutton (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1988), 16–49. ↩

- Josh Berson, Computable Bodies: Instrumented Life and the Human Somatic Niche (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015). 40. ↩

- B. D. Kristensen and M. Ruckenstein, “Co-Evolving with Self-Tracking Technologies,” New Media and Society 5, no. 3 (2018): 219–38. ↩

- Sherry Turkle, Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in a Digital Age (New York: Penguin, 2015). ↩

- Jonathan Safran Foer, “’How Not to Be Alone,” New York Times, June 8, 2013, https://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/09/opinion/sunday/how-not-to-be-alone.html. ↩

- S. Marche, “Is Facebook Making Us Lonely?,” Atlantic, May 2012, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2012/05/is-facebook-making-us-lonely/308930/. ↩

Bibliography

- Albrechtslund, A. “Online Social Networking as Participatory Surveillance.” First Monday 13, no. 3 (2008). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v13i3.2142.

- Berson, Josh. Computable Bodies: Instrumented Life and the Human Somatic Niche. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015.

- Foer, Jonathan Safran. “’How Not to Be Alone.” New York Times, June 8, 2013. https://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/09/opinion/sunday/how-not-to-be-alone.html.

- Foucault, M. “Technologies of the Self.” In Technologies of the Self: A Seminar With Michel Foucault, edited by L. H. Martin, H. Gutman, and P. H. Hutton, 16–49. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1988.

- Galič, M., T. Timan, and B. J. Koops. “Deleuze and Beyond: An Overview of Surveillance Theories from the Panopticon to Participation.” Philosophy and Technology 30, no. 1 (2016): 9–37. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-016-0219-1.

- Giddens, Anthony. Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1991.

- Jakala, A., and E. Berki. “Exploring the Principles of Individual and Group Identity in Virtual Communities.” IADIS International Conference Web Based Communities, n.d., 19–26. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267794585_EXPLORING_THE_PRINCIPLES_OF_INDIVIDUAL_AND_GROUP_IDENTITY_IN_VIRTUAL_COMMUNITIES.

- Kristensen, B. D., and M. Ruckenstein. “Co-Evolving with Self-Tracking Technologies.” New Media and Society 5, no. 3 (2018): 219–38.

- Lupton, Deborah. The Quantified Self. Cambridge: Polity, 2016.

- Mann, T., D. de Ridder, and K. Fujita. “Self-Regulation of Health Behavior: Social Psychological Approaches to Goal Setting and Goal Striving.” Health Psychology 32, no. 5 (2013): 487–98. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028533.

- Marche, S. “Is Facebook Making Us Lonely?” Atlantic, May 2012. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2012/05/is-facebook-making-us-lonely/308930/.

- Moore, Phoebe, and Andrew Robinson. “The Quantified Self: What Counts in the Neoliberal Workplace.” New Media and Society 18, no. 11 (2016): 2774–92.

- Thumin, Nancy. Self-Representation and Digital Culture. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

- Townsend, A. M. “SMART CITIES: Big Data, Civic Hackers, and the Quest for a New Utopia.” Stanford Social Innovation Review, 2013. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.48558/BXTE-BQ78.

- Turkle, Sherry. Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in a Digital Age. New York: Penguin, 2015.

- Ziebland, Sue, and Sally Wyke. “Health and Illness in a Connected World: How Might Sharing Experiences on the Internet Affect People’s Health?” Milbank Quarterly 90, no. 2 (2012): 219–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2012.00662.x.