Reflection 2: About This “Book”

… academic research was published as continuous print, in the form of a physical book. Your publisher might have agreed to a dozen illustrations, often inserted on glossy paper in the middle of the book; you might also have haggled for some black-and-white line drawings along the way. Your book would have had a hard cover, with a paper dust jacket – to keep dust out! – printed with an eye-catching image on the front, text on the inner flaps (about the book at the front, about the author at the back) and summary information on the back, usually including some blurbs intended to encourage potential purchasers. The oldest dust jacket is said to be one from 1829, for an English annual, unearthed in 2009; it lives in the Bodleian Library in Oxford.

In 2019 the Ego Media research group based at King’s College London were coming to the end of their five-year grant from the European Research Council. All sorts of “outputs” had been put out into the world in furtherance of publishing the group’s research findings: books, articles, online journal special issues, PhDs (in both print and e-versions), plus other forms of disseminations, including an exhibition, talks, lectures, podcasts, workshops, conference panels, digital avatars…given the variety, volume, and spread of the material, the form of final publication seemed to exceed what it might be possible to round up in a printed book. Besides, given the subject – life writing in the digital age – it seemed suitable to explore digital publishing options in terms of evolving from the printed book which, though it remains magical technology, was not the best media to convey either the findings or the spirit of Ego Media. Digital text may attract digital researchers more; it may also be accessible to different kinds of readers and draw in new audiences. Thanks to the financial support of the European Research Council and Stanford University, our research can be Open Access, free of paywalls and subscriptions.

Although authors have been writing computer-based interactive works of literature since the 1970s, the digital book is still in its early days: set against the codex’s 1,500-year life-span, e-lit’s (e-literature’s) mere 40 years is almost nothing. Currently (2019) the term digital book still mostly means an e-book, a book in digital file form, suitable for display on e-readers (like Kindle) or i-readers (like the iPad). There are still relatively few books that are “born digital” in the sense that they are structured and written to be read/experienced on screens, rather than read on paper, and which – were they to be ported in print – would require significant reworking. In 2011, Mike Matas of Apple showed off a next-generation digital book, with features including audio, moveable images, zoom, animations, video, and interactive infographics.1 “Anything you can see in the book, you can pick up with two fingers,” said Matas. The text was Al Gore’s Our Choice: A Plan to Solve the Climate Crisis (a sequel to his 2006 film/documentary about climate change, An Inconvenient Truth.) Al Gore’s website recommends the digital book, which it describes as an app, in the warmest terms:

Our Choice will change the way we read books. And quite possibly change the world. In this interactive app, former Vice President Al Gore surveys the causes of global warming and presents groundbreaking insights and solutions already under study and underway that can help stop the unfolding disaster of global warming. The Our Choice app melds Vice President Gore’s narrative with photography, interactive graphics, animations, and more than an hour of engrossing documentary footage. A new, groundbreaking multi-touch interface allows you to experience that content seamlessly. Pick up and explore anything you see in the book; zoom out to the visual table of contents and quickly browse though [sic] the chapters; reach in and explore data-rich interactive graphics.2

In the years since, reading on phones has become commonplace, and the e-book share of the market has consolidated: “In 2018, a quarter of all books sold so far have been e-books, and that figure doesn’t include audiobooks, which in turn make up another 18% of the market.”3 Assisted by Alexa (reading books aloud via one of Amazon's Echo devices) or Marvin 3 (a multifeature i-app), digital reading forms are evolving – though physical books and bookshops are also doing (surprisingly?) well. The book’s endurability was celebrated by IKEA’s 2015 catalog, parodying Apple launches of new products by introducing the simple and intuitive “bookbook,” that is, a book, with features like eternal battery life and tactile touch technology.4 Even conservative publishers now issue e-books. Often but not always cheaper than print editions, e-editions can also break up books: an academic essay collection, for instance, can be filleted into chapters for individual sale in ways that detach research from a body (for instance, the connective tissue of an introduction.)

In making a digital book, Ego Media researchers have settled on the term hybrid to explain their “book”: not an e-book, not an i-book, not a website, but with some features found in all of those. Like hybrid cars, combining a traditional combustion engine with an electric motor, or even like hybrid electric cars, supplying power to a vehicle’s drivetrain by a range of different means, a digital/book combines some of the features of traditional print with possibilities enabled by digital functions. The learning curve has been steep. Some ideas exceeded possibilities, some exceeded budget. To build in reader responses, for instance, you need a moderator, a commitment beyond our means. One idea, defeated in part by budget, was to build a chatbot who could add a responsive, imaginative, and informative dimension, like a cheerful tour guide. Chatbots are becoming increasingly standard in library platforms; the preservation of chatbots as part of digital history is, at the time of writing, something in which research libraries like the British Library are becoming interested. It seemed entirely suitable to include artificial intelligence agents among Ego Media researchers, since AI is increasingly part of digital research ostensibly undertaken by humans. There is, however, a risk that the more complex the structure, the more challenging it is for readers – and the more difficult to secure in terms of digital sustainability.

The evolution of e-readers and digital reading has coincided with increased awareness of climate change and environmental crisis. What are the environmental costs of a digital book relative to a paper one? It’s hard to calculate: where printed books use trees, inks, power for processes of printing, binding, distribution, and promotion, digital books use less visible or traceable forms of power for creating, sustaining, and using online content. Equivalences are hard to establish. Digital devices – notoriously with short-life battery power which needs regular recharging – are implicated in fossil fuel economies for running and for storing information. The energy cost of cloud storage is conveniently ignored by many. As three Italian researchers put it,

The ICT (Information Communication Technologies) ecosystem is estimated to be responsible, as of today, for 10% of the total worldwide energy demand – equivalent to the combined energy production of Germany and Japan. Cloud storage, mainly operated through large and densely-packed data centres, constitutes a non-negligible part of it. However, since the cloud is a fast-inflating market and the energy-efficiency of data centres is mostly an insensitive issue for the collectivity, its carbon footprint shows no signs of slowing down.5

A Carnegie Mellon University study concluded that the energy cost of data transfer and storage is about 7 kWh per gigabyte. An assessment at a conference of the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy reached a lower number: 3.1 kWh per gigabyte. (A gigabyte is enough data to save a few hundred high-resolution photos or an hour of video.)

Compared with your personal hard disk, which requires about 0.000005 kWh per gigabyte to save your data, this is a huge amount of energy. Saving and storing 100 gigabytes of data in the cloud per year would result in a carbon footprint of about 0.2 tons of CO2, based on the usual US electric mix.6

Some providers use renewable sources of power for clouds, but not many. And cloud is a misleading term, or one that disguises how cloud companies in fact store data on …hard disks. These need regular replacing. They are held inside data centers, or buildings by any other name.7

It has been estimated that

The communications industry could use 20% of all the world’s electricity by 2025, hampering attempts to meet climate change targets and straining grids as demand by power-hungry server farms storing digital data from billions of smartphones, tablets and internet-connected devices grows exponentially.8

Data farms take up real-world space as well as energy: “The scale of these farms is huge; a single $1bn Apple data centre planned for Athenry in Co Galway, expects to eventually use 300MW of electricity, or over 8% of the national capacity and more than the daily entire usage of Dublin.” 9

The Green Grid Association, a voluntary ICT industry body, provides metrics for power usage effectiveness, or PUE, and data center infrastructure efficiency, or DCIE.10 These are hardly at the forefront of consumer awareness – yet – or promoted with anything like the same visibility as marketing terms like quick, secure, safe, and resilient as factors relevant to cloud storage options. Ease-of-use and human convenience trumps environmental concerns.

Other hidden environmental costs include the consequence-laden heavy metals used in the manufacture of digital devices, especially phones.11 An article in TechRadar notes exact constituents are hard to identify because of trade secrets. Nonetheless, most smartphones use sixteen of the planet’s seventeen rare metals. “Overall, a smartphone handset consists of around 40% metals (predominantly copper, gold, platinum, silver and tungsten), 40% plastics and 20% ceramics and trace materials.” Tin, tantalum, tungsten, and gold are recognized as conflict-zone materials by manufacturers, some of whom (like Fairphone) commit to ethical standards, including better recycling. Extraction of these metals – and copper, silver, and others – is often environmentally very damaging, for instance when tailings – ore waste from mines – pollute waterways or break through dams.12

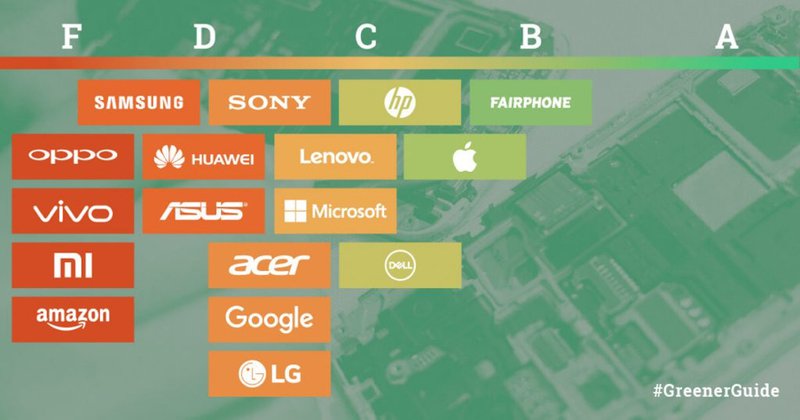

A Greenpeace Guide to Greener Electronics of 2017 compared the environmental practices of smartphone manufacturers – specifically, energy use, resource consumption, and chemical elimination:

Manufacturers are scored on a scale of F (worst) to A (best).as follows:

Low F

oppo

vivo

mi

amazon

High F

Samsung

Low D (there's no E)

Huawei

Asus

Mid D

Sony

acer

LG

High D

Lenovo

Microsoft

Low C

HP

Dell

High C

Apple

Low B

Fairphone (highest score).

and noted:

Worldwide e-waste volumes are expected to surpass 65 million metric tons in 2017. While a number of brands now offer some voluntary take-back programs, there is little if any reporting on what is actually being collected or where it goes upon collection. The end result: less than 16% of global e-waste volumes are estimated to be recycled in the formal sector, despite the valuable materials contained within. Often “recycled” e-waste ends up at informal recyclers and handled in ways that endanger worker health and the local environment.13

The lack of transparency about supply chains and manufacturing processes exacerbates damage to both planet and humans – many horrors get hidden, including the damage inflicted on people by the activities of powerful multinational companies: sickness, poverty, lack of rights, injustice, corruption, social instability, authoritarianism, and violence afflict workers and residents, while company profits are protected, often by bribery and force. Despoliation is only going to get worse as mining companies eye up deep ocean sites that hold rare earth metals, including seamounts (cobalt-rich crusts), abyssal plains (metallic nodules), and hydrothermal vents (copper, gold, and other metals), whose life-forms have no means of protest, no chance of survival, and no prospect of habitat recovery. Resource extraction sounds neutral, but there is no neutralizing or repairing much of the damage it causes.

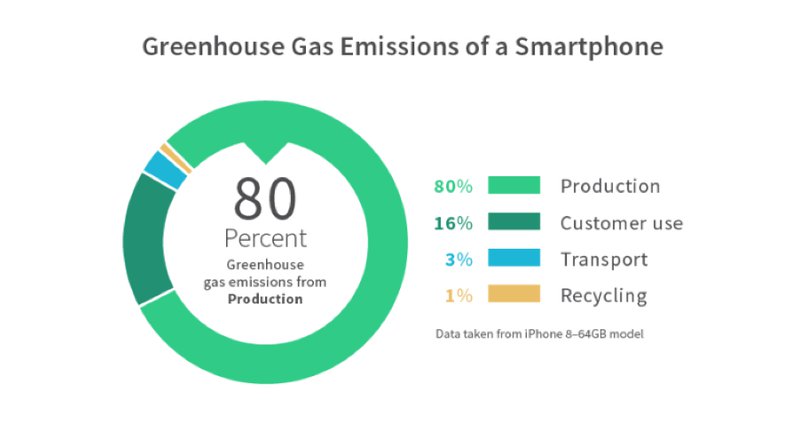

The wider environmental and societal costs of digital are often curtained off from the more consumer-friendly question of carbon footprint. The 2017 Greenpeace report has another infographic neatly detailing the smartphone’s contribution to greenhouse gas:

The 16 percent created by customer use is a slippery figure in terms of further energy costs, also hidden. One perennial question concerns what is the carbon footprint of a Google search? One calculation has it that two Google searches is equivalent to boiling a kettle, though Google refutes the maths and provides a different model.14

Ego Media research has certainly entailed thousands of online searches, each with a carbon footprint. Life writing as an area of research and practice aims to engage with the full diversity of lived human experience. Writers and readers need to be conscious of how human experience also impacts on and interferes with the planet’s ecological narrative – a narrative that supports us all. Neither making nor reading this “book” is an environmentally neutral enterprise. We hope reading it is worth the cost to the planet.

Endnotes

- Mike Matas, “A Next-Generation Digital Book,” TED, 2011, https://www.ted.com/talks/mike_matas_a_next_generation_digital_book. ↩

- No longer available, but see archived version at https://web.archive.org/web/20210629211518/https://algore.com/library/our-choice-app. ↩

- See https://fueled.com/blog/best-apps-for-book-lovers/, though it has been updated since the writing of this. ↩

- See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LNsmaQOP-OE. ↩

- Lorenzo Posani, Alessio Paccoia, and Marco Moschettini, “The Carbon Footprint of Distributed Cloud Storage,” June 26, 2019, https://arxiv.org/pdf/1803.06973.pdf. ↩

- Justin Adamson, “Carbon and the Cloud: Hard Facts about Data Storage,” Stanford Magazine, June 2017, https://stanfordmag.org/contents/carbon-and-the-cloud. ↩

- One paradigm is outlined in Tim Nufire, “The Cost of Cloud Storage,” Backblaze, June 29, 2017, https://www.backblaze.com/blog/cost-of-cloud-storage/. ↩

- “‘Tsunami of Data’ Could Consume One Fifth of Global Electricity by 2025,” The Guardian, December 11, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/dec/11/tsunami-of-data-could-consume-fifth-global-electricity-by-2025. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- See https://www.thegreengrid.org/sites/default/files/tgg_about-us_timeline_v4.pdf. ↩

- David Nield, “Our Smartphone Addiction Is Costing the Earth,” TechRadar, August 4, 2015, https://www.techradar.com/news/phone-and-communications/mobile-phones/our-smartphone-addiction-is-costing-the-earth-1299378. ↩

- Marianela Jarroud, “Mine Tailings Pollute a Chilean Town’s Water,” Interpress Service News Agency, June 14, 2012, http://www.ipsnews.net/2012/06/mine-tailings-pollute-a-chilean-towns-water/. ↩

- Gary Cook and Elizabeth Jardim, “Guide to Greener Electronics 2017,” Greenpeace Reports (Greenpeace, October 17, 2017), https://www.greenpeace.org/usa/reports/greener-electronics-2017/. ↩

- Cook and Jardim, “Guide to Greener Electronics 2017.” ↩

Bibliography

- Adamson, Justin. “Carbon and the Cloud: Hard Facts about Data Storage.” Stanford Magazine, June 2017. https://stanfordmag.org/contents/carbon-and-the-cloud.

- Cook, Gary, and Elizabeth Jardim. “Guide to Greener Electronics 2017.” Greenpeace Reports. Greenpeace, October 17, 2017. https://www.greenpeace.org/usa/reports/greener-electronics-2017/.

- Jarroud, Marianela. “Mine Tailings Pollute a Chilean Town’s Water.” Interpress Service News Agency, June 14, 2012. http://www.ipsnews.net/2012/06/mine-tailings-pollute-a-chilean-towns-water/.

- Matas, Mike. “A Next-Generation Digital Book.” TED, 2011. https://www.ted.com/talks/mike_matas_a_next_generation_digital_book.

- Nield, David. “Our Smartphone Addiction Is Costing the Earth.” TechRadar, August 4, 2015. https://www.techradar.com/news/phone-and-communications/mobile-phones/our-smartphone-addiction-is-costing-the-earth-1299378.

- Nufire, Tim. “The Cost of Cloud Storage.” Backblaze, June 29, 2017. https://www.backblaze.com/blog/cost-of-cloud-storage/.

- Posani, Lorenzo, Alessio Paccoia, and Marco Moschettini. “The Carbon Footprint of Distributed Cloud Storage,” June 26, 2019. https://arxiv.org/pdf/1803.06973.pdf.

- The Guardian. “‘Tsunami of Data’ Could Consume One Fifth of Global Electricity by 2025.” December 11, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/dec/11/tsunami-of-data-could-consume-fifth-global-electricity-by-2025.