To-Day and To-Morrow Online: Technology, Futurology, and Networked Self-Presentation

This site-section focuses on the imagination of the future prompted by new technologies such as the internet. It consists of two parts: first, Max Saunders’s study of the major book series from the 1920s and 1930s called “To-Day and To-Morrow” and the ways in which it anticipated the kinds of development of communication studied by Ego Media; and second, an account of the curated series of talks, discussions, and interviews staged by Ego Media, called “Life Online To-day and To-morrow,” in which some of today’s best analysts and commentators consider the effects of digital and social media now and speculate about their future impacts.

One of the distinctive perspectives that Ego Media’s literary and cultural analysts bring to the study of online lives is a historical view, which contextualizes the evolution of new cultural forms, while continually questioning that novelty. The point is not to negate the very real differences of contemporary digital culture, but to bring them into sharper focus by trying to distinguish the aspects which have precedents from those which seem genuinely unprecedented.

T. S. Eliot, to whom the World Wide Web and social media would doubtless have seemed a Waste Land worse than any he could have imagined, said of the really new in art:

What happens when a new work of art is created is something that happens simultaneously to all the works of art which preceded it. The existing monuments form an ideal order among themselves, which is modified by the introduction of the new (the really new) work of art among them. The existing order is complete before the new work arrives; for order to persist after the supervention of novelty, the whole existing order must be, if ever so slightly, altered; and so the relations, proportions, values of each work of art toward the whole are readjusted; and this is conformity between the old and the new. Whoever has approved this idea of order, of the form of European, of English literature will not find it preposterous that the past should be altered by the present as much as the present is directed by the past.1

If we might want to describe this aesthetic position as an interactive theory of cultural change, it is partly because the fragmentation, montage, and heteroglossia of platforms like Twitter or Instagram seem at once utterly incommensurable with the modernist quest for significant form and also a set of uncanny echoes of modernist preoccupations – with the impenetrability of subjectivity; the play of constructed identities; the transactions between text, image, sound, and film.

Another way of putting it would be to say that, on the one hand, we can see early twentieth-century culture as struggling to accommodate itself to technologies still new – the telephone, radio, cinema, internal combustion engine, telegraph, typewriter, television, aviation, and so on – in the same way that our era is reimagining aesthetics in the age of the computer, the internet, and artificial intelligence. Whereas, on the other hand, our contemporary obsession with the digital world frames how we think about the past too. It provides an example of what Eliot means by the present altering the past. From that point of view, the early twentieth century isn’t set apart as the twilight of the pre-digital age. It is the age in which many of our concerns with digital life and culture were first beginning to take form.

The design of Ego Media’s To-Day and To-Morrow section reflects this duality by juxtaposing two chronologically distinct strands.

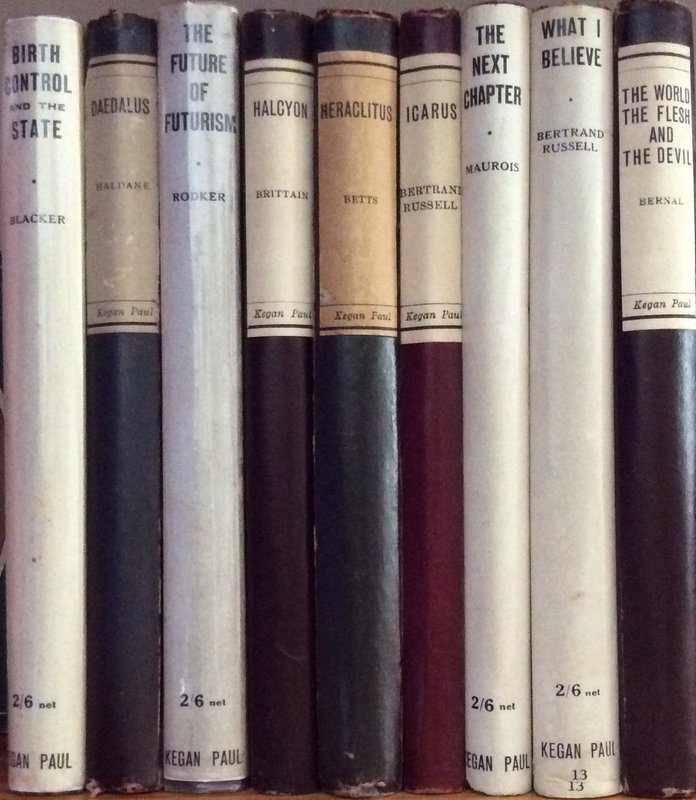

One is a study of an unusual book series published a hundred years ago, devoted primarily to predicting the future across a range of disciplines. It was called “To-Day and To-Morrow,” edited by the polymath intellectual C. K. Ogden between 1923 and 1931, and published by Kegan Paul in the UK and E. P. Dutton in the US. My book Imagined Futures 2 is the first full-length study of the entire series and makes the case for its importance in a number of ways and in many fields. What concerns us here, though, is the extraordinary way in which its visions of the future repeatedly appear to anticipate our digital situation. This is partly an instance of Eliot’s notion of reverse influence: the concerns of the digital present projecting themselves back and rearranging the – after all – pre-digital past. But it is much more than that. Rather, we see the writers of the modernist period framing the visions and desires that the internet and the World Wide Web have found new ways to realize.

The 110 short books of To-Day and To-Morrow – they were really essays or pamphlets published as elegant hardback pocket-books – were not only concerned with technological predictions. They imagined the futures of society, politics, the relations between the sexes, leisure, culture, education, intelligence, and much else besides. Sustaining their projections over a greater length than the more usual journalistic futurological fare of jetpacks and flying cars meant that they imagined what it would be like to live in a world of new technologies, and the new social and institutional organizations that would develop in parallel with them. To that extent the series offers a curious form of life writing: an attempt to imagine future lives. Contrasting it with contemporary thinking about trends in new media brings into focus the extent to which our responses to technological developments involve rethinking time and imagining the future. These ideas of how new media prompt us to imagine the future and write future lives are central to Ego Media.

2. Life Online Today and Tomorrow talk series

The second major strand in this section/project consists of a reflective essay on the series of lectures and discussions staged by Ego Media called “Life Online Today and Tomorrow,” which sought to take soundings from a group of leading thinkers and theorists of life in our current media ecology about the impact the new web technologies have already had on us and how they might develop in the future.

Part of the argument of Imagined Futures is that the study of past visions of the future enables us to become better futurologists, or at least to understand better how futurology works; why it goes right when it does; why it goes wrong, which it does more often; and why blind spots appear in specific areas. Ego Media’s juxtaposition of the original To-Day and To-Morrow series with early twenty-first century thinking about new communication technologies has three main aims:

- To read the earlier predictions in the light of current developments and media theory

- To enable new understandings of contemporary media analysis and prediction through comparison with the earlier versions

- To provide a comparative archive to enable the enhancement of future thinking

You can visit the two main parts of this site section from here:

The original To-Day and To-Morrow book series

Ego-Media’s Life Online Today and Tomorrow talk series