“Future” Wars

This subsection considers imagined and projected wars of the future that may, actually, already be playing out in online spaces. These rely on competing technologies and media that may or may not help humans to diffuse future conflicts and existential threats like climate change. This depends on our capacity to use social media tools to render intelligible and empathetic complex networks and systems.

Writing for the multimedia platform War on the Rocks in June 2018, analysts David Barno and Nora Bensahel describe a sense of anxiety amongst Chinese military officials and analysts who, imagining future wars, worry about their army’s lack of combat experience relative to other military powers. Yet Barno and Bensahel argue that a myopic focus on combat relies too much on “embedded assumptions.”1 Time and experience can become circular when it comes to war: “Thinking about the next war can be too easily bounded by projecting past experiences forward, a natural human tendency to think linearly about what might be, colored by what has been.” The US military has also been slow to react to the “Fourth Industrial Revolution [which] promises to be unprecedented in both its global effects and its disruptive power.” They identify the following particular areas of interest for strategic planning: space and cyber; AI, big data, machine learning, autonomy, and robotics; the return of mass and defensive advantage; and new generations of high-tech weapons. Finally, they write of the “unknown x-factor,” which cannot be fully anticipated: they recommend a focus on stories (including P. W. Singer and August Cole’s Ghost Fleet (2016), the latter’s Automated Valour (2018), and Daniel Suarez’s drone narrative Kill Decision (2013) to “help creative military leaders imagine the unimaginable, and visualize how the battles of the next war may play out in ways the lens of the past fails to illuminate.”2 And yet, as Lawrence Freedman has argued, a “number of factors make it hard to anticipate the future. One is that prediction is often purposeful, closely bound up with advocacy, and so is about the present as much as the future.”3 This certainly feels like an applicable caveat to introduce to this article, as to any discussion about future conflicts.

How modern militaries adjust to expanding technological threats from states and individuals is one element of defense studies; military academies return again and again to the classic case study of the French army in 1940, which adhered to a long-standing doctrinal plan based on the idea of methodical battle, all as the German Army used technological advances to enact their highly mobile blitzkrieg.4 Soldiers and civilians also need to understand when and why mobilizations might be required, and, where they have the means, whether or not to bestow their political consent. What will future techs’ promised openness and increased transparency deliver in the field of war studies and adjacent disciplines? Dave Maass, in a futurist essay for the 2018 McSweeney’s Quarterly, produced in partnership with the nonprofit Electronic Frontier Foundation, devoted to surveillance in the digital age, imagines Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests. Taking it as a given that “a decade from now, governments will be sitting on larger stacks of data and bureaucratic paperwork than ever before,”5 he presents a scenario in which a reporter who had, in the early 2000s, reported on the war in Iraq requests access to newly declassified material. Will her request be handled by a human reviewer, or will it be turned over to an AI software like the Sensitive Content Identification and Marking technology currently being developed by the US Central Intelligence Agency and the University of Texas at Austin. Maass points out that, “Done right, the software could process records more quickly than any team of humans and provide a baseline review for a process that is highly objective. Done wrong, the programme could justify new levels of secrecy that would simply be rubber-stamped by a human operator.”6

The combined power of human and nonhuman actors, armed with social media, to undermine civic discourse and behaviors has been thrown into sharp focus in recent years. In her detailed study of coordinated Russian troll attacks on the 2016 US election, Kathleen Hall Jamieson details the mobilization and demobilization of groups of voters through targeted advertisements across a number of social media platforms. She also shows how both the content of these advertisements and the quantitative reaction to them – by actual users and bots alike – led established news organizations to adopt, at least in part, the false narratives and opinions they pushed across screens. As a result of a combination of platform design and failing to anticipate and react, “Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, YouTube, and Tumblr were among the tech giants that unwittingly became conduits for Russian propaganda.”7 This activity is grouped under the heading of “cyberwar” (which is also the title for Jamieson’s book) and yet, given the absence of violence, Clausewitzian scholars would not consider this activity to be war. The boundaries are as yet unclear: popular rhetoric describes these interventions as “attacks,” and their effects can be extreme, even deadly. Societies will need to think more carefully about where this activity falls and which institutions are assigned to respond to it.

The creation and dissemination of false information designed to go viral across social media platforms is now also a private industry. In May 2019 the blog forum Medium published a story by Karen Kanishk and the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab) about the Israel-based Archimedes Group and Facebook; the story was retweeted by Andy Carvin on May 17, 2019. The latter had announced that they would remove Facebook and Instagram assets and accounts associated with the political marketing firm because they had engaged in “coordinate inauthentic behavior” targeting users in, in particular, Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia. The article reports that the group’s activities “closely resemble the types of information warfare tactics often used by governments, and the Kremlin in particular. Unlike government-run information campaigns, however, the DFRLab could not identify any ideological theme across the pages removed, indicating that the activities were profit-driven.”8 Recent investigative reporting linking disparate topics, including US local election cyberattacks and the #MeToo movement, details the activities of ex-Mossad agents working in the private sector on behalf of individual and state actors around the world to spread targeted misinformation.9,10 This is hardly novel practice – as Peter Wilson’s European Fiscal-Military Project considering urban hubs and networks from 1530 to 1870 proves – even as online resources might have shifted the character of activity.11 Such campaigns remind us of the long history of opacity associated with networks and disinformation campaigns derived from military necessity – the black boxing of online interactions, as Rebecca Roach conceives of it.12

Online campaigns have offline manifestations. In May 2019 the Borderline Watch project reported on how Bulgarian border patrols, acting as self-styled paramilitary groups, were performing “civic arrests” of migrants and refugees. The groups involved had begun online as quasi-military avatars, where they developed ideologies typical of international far-right groups: anti-Semitism, anti-Islam (linked, in the Bulgarian case, to anti-Turkish rhetoric), anti-NATO, and anti-EU. Their postings dovetail with pro-Russian propaganda campaigns: they have imported particular “lexical constructs” that mirror separatist “branding” displayed in parts of the Eastern Ukraine. The groups are working to achieve a “mobilization state,” free of political parties, where the “greedy and useless political party elites” are served strict punishments.13

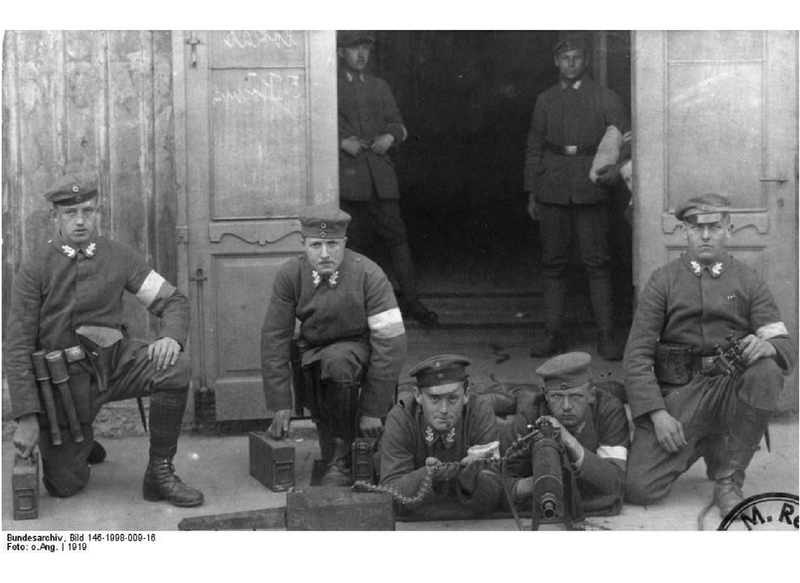

Disaffection produces a desire for some form of projected action, particularly for individuals who define their identities through real or imagined military lenses. Robert Gerwarth provides a historical example of this phenomenon, writing about how the First World War did not really end in 1918. Instead defeated European armies returned to fragmented and volatile societies. A not insubstantial minority spread – in drip feed – “cycles of violence” into political cultures across the continent.14 Subsequent conflicts ensued: Martin Conway, Pieter Lagrou, and Henry Rousso have made a strong case for the idea that we are all still living through, and dealing with the consequences of, Cold War demobilizations.15

The nature of the sporadic eruptions, concentrated in pockets, then flaring and flailing, provides a parable for the social media age. Online violence, in the form of incitements to hate crime, attacks on individuals and groups, with offline manifestations and consequences is proliferating across the wired and wireless world, spread by disaffected humans and amplified by bots. It is now a focus, particularly with respect to the spread of far-right open-source investigation sites like Bellingcat. In recent months and years they have published articles on how to search for evidence of extreme radicalization on platforms like 8chan and Gab – including, for example, how a particular meme spread, ultimately linking three (and likely more) violent fascists.16,17 Robert Evans, who reports on war and digital radicalization for Bellingcat, previously worked as a conflict reporter covering Iraq and the Ukraine. He provides an example of how mainstream journalists have honed their online investigative capacities to uncover how individual stories might fuel broader social and political ruptures.

In some extreme but likely not exceptional instances, the programmatic spread of violence runs through official, state-sanctioned channels, aided by technological corporations. In Myanmar, the military – exploiting the platform’s capacity to enable large-scale trolling and to amplify propaganda – systematically used Facebook to incite rape, murder, and forced migration against the Muslim Rohingya minority in a country where, the New York Times reported, “the country’s 18 million internet users confuse the Silicon Valley social media platform with the internet.”18

Offering a more hopeful example of how institutional perspectives can shift in the digital age, when armed with data about the future conditions for violence from the perspective of infrastructure and security, in February 2019 the Centre for Climate & Security blog compiled a chronologic summary of testimonials from the US security world that counter misleading statements and rhetoric offered by spokespeople on the right about the link between global climate change and war. Representatives from the various armed services testified to the changes they had personally witnessed and the implications for the future – storms and displaced persons, food insecurity and droughts, melting ice caps, etc. The AFRICOM Commander, General Thomas D. Waldhauser, USMC (Ret) offered one example from his own experience in March 2018: “I would say from the climate perspective, is that we have seen the Sahel – the grasslands of the Sahel – recede and become desert almost a mile per year in the last decade or so. This has a significant impact on the herders who have to fight, if you will, for grasslands and water holes and the like…So these environmental challenges put pressure on these different organizations — some are VEO [violent extremist organizations], some are criminal, but it puts pressure on these organizations just for their own livelihood.”19 Waldhauser is not the first military commander contending with climate change; in Global Crisis (2017) Geoffrey Parker describes how such threats inflected seventeenth-century wars and military planning,20 and the British Army’s Future Operating Environment 2035 also reflects a broader Western military mindset that recognizes climate change as the core threat.21 How war is framed is shifting as human anxieties about the future merge with other self-induced threats, leading to coordination across organizations and producing an interesting scenario where traditionally conservative institutions operate as major advocates for climate action.

Stories emerging from any number of expected and unexpected conflicts zones, told from a variety of perspectives and produced in accessible digital media that communicate the effects of conflict on individuals and societies, can reach an international audience, inspiring movements that promote identification, empathy, and cooperation. Digital literacy is not ubiquitous or evenly distributed; older users, including veterans of past wars, are less active on social media platforms, meaning that their voices and opinions may be omitted from the increasingly digital and digitized public record. Offline organizing is still required, as are spokespeople. Writing in April 2019 in the London Review of Books the Philadelphia-based radiation oncologist Patrick Tripp reminds readers of the centrality of health narratives to debates about past, ongoing, and future wars: as one veteran after the next visits the doctor’s office for their check-up, they tell him their stories, relaying the complex ways war manifests itself in family life.22 Public health narratives like these center long-term conditions and trauma management as a key topic for war writers and news organizations covering conflicts.

Narratives about conflict and climate take a variety of media forms. The 2019 Icelandic black comedy Kona fer í stríð – or Woman at War – directed by Benedikt Erlingsson plays with, and ultimately reconfigures, the warrior narrative to tell the story of an increasingly desperate climate campaigner’s battle – armed with bow, arrow, and resolve – against apathy and heavy industry assaults on the planet.

At the same time, the hero of the story is looking to the future as she attempts to adopt a child: this is both a family narrative and a global one. Juan Cole, whose Informed Comment blog emerged as a reference for many independent readers as well as gatekeeper institutions and organizations in the wake of the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, now frames the mission of the site as follows: “Informed Comment sheds light on how war, climate change and globalization are shaping our world,”23 with a range of authors with expertise across these topics now contributing. This stands in contrast to the blog’s initial focus and Cole’s specific area of expertise, which was very much on information analysis as it related to the war in Iraq. The National Geographic Instagram feed @natgeo, which has over 110 million followers at the time of writing, mixes photography of nature’s grandeur and human endeavor with images of conflict and climate change, and the destroyed landscapes and refugees – human and other – they create. (Not entirely unexpectedly, as climate change becomes a pressing concern for majority constituents, right-wing ethno-nationalists are adopting “green” aesthetics and rhetoric, pointing to the role it is playing in driving mass migrations.24)

These established and emerging war writers are not alone in expanding their foci, approaching conflict narratives through a lens that is both ancient and increasingly present: the fight for safety, security, and resources. The veteran and writer Mariette Kalinowski (@skiattq), author of “The Train,” rarely tweets; on November 9, 2016, in the wake of the US election results she posted that she would be “fasting” from Twitter, Facebook, etc. because “it creates an unhealthy environment for me. The election coverage spiked my stress in ways not seen since I deployed.”

Her next tweet, in August 2017, was a reposting of an article written by fellow veteran writer Roy Scranton for the New York Times.

Scranton’s piece – tagged with #Harvey #Anthropocene – imagines a future climate catastrophe, “When the Next Hurricane Hits Texas.” As Max Saunders has argued,25 he joins a long line of writers whose postwar imaginations turn to the destruction of urban landscapes. He deploys his considerable skills in describing human displacement and the destruction of the vulnerable, industrialized landscape, which he describes in detail, as though it has already happened, only part-way through the narrative, making clear to the reader that this is a projection. Writing about our ability to organize against this future assault, he draws parallels between how humans cope with other culturally endorsed, self-inflicted catastrophes:

That’s the human way: reactive, ad hoc, improvised. Our ability to reconfigure our collective existence in response to changing environmental conditions has been our greatest adaptive trait. Unfortunately for us, we’re still not very good at controlling the future. What we’re good at is telling ourselves the stories we want to hear, the stories that help us cope with existence in a wild, unpredictable world.26

Considering this conclusion to Scranton’s article, which blends dystopian imaginative agency and nonfiction reporting, it is not difficult to understand why some war writers shift easily between what were once seen as disparate topics: war and climate catastrophes. Historically speaking, military organizations such as the Mississippi Valley Division of the US Army Corps of Engineers, which oversees flood defenses across the central and southern states has, for many years, been at the forefront of climate mitigation efforts. Its work, and the broader conceptual framework articulated in Scranton’s writing, points to a potential shift in the role for Western militaries, which will be required to play a more central role in public life: moving away from fighting forces to disaster response services.

These writers, and many others, are now working in an anticipatory, cooperative mode. Like their readers, they are armed with vast amounts of information and numerous models capable of predicting – to a degree – human futures and conflicts. Some articulate experienced and impending violence by focusing on individual stories, while others writers who have survived and/or witnessed modern wars feel compelled to take a step back. Their offshoot narratives encourage readers to reflect on how we all, through our life stories and practices, as social actors, contribute incrementally to the conditions that will lead to an increase in conflict and suffering across the globe, now and in the future. And, in writing about these future wars, they attempt – sometimes seemingly without any hope at success – to diffuse and avoid them.

But as with other areas of social discourse, the media landscape in which war writers work and readers exist is, to state the obvious, complex and disparate. Information and data derived from social media, or climate monitors, are both deep and wide in their scale and scope, and there is no consensus about how the material should best be used. In 2013 the online war writer John Little wrote that, as opposed to producing official or “overt” social media content, “I believe that governments would benefit from far fewer overt accounts and many more covert ones. Every military unit and bureaucratic department has its own neglected Twitter account now. They do nothing to advance the strategic or tactical goals of their government.”27 Written in 2019, this is a somewhat chilling statement that also articulates the utilitarian approaches to social media warfare: framing it as a tool that must be used in conflicts. It helps to illustrate the spectrum of opinion and the extent to which assumptions frame discourse. For example, in “War in the Fourth Estate” Barno and Bensahel write as though future war is inevitable.28 And yet there are differences in institutions’ approaches to social media. The Ship’s Cat Twitter feed (@R08Cat) of HMS Queen Elizabeth maintained by the Royal Navy is simultaneously funny, silly, and effective in its messaging: it reminds its followers of the role of humor in all wars and invokes a seemingly universal human and hence online obsession (anthropomorphic pets). Given the composite online and offline threats and discords facing humanity in the twenty-first century – and the cumulative historical evidence of conflicts, played on a series of loops – the full spectrum, from the inevitability of future conflict to our common humanity, is reflected in these online war narratives.

In an age when third-party and self-surveillance is ascendant, engagement with and management of life in relation to conflict narratives becomes ever more fraught, particularly as cyberwars spread. Is our data contributing to future war stories or resisting them? Is there any way to secure the online? Clare Birchall, writing about information in the post–[Edward] Snowdon era, attempts to define the complex reality: “We are within a dynamic sharing assemblage: always already sharing data with human or non-human agents...the subject of shareveillance is one who simultaneously works with data and on whom the data works.”29 In this online world traditional notions of autonomy and agency are called into question.

When are we at war, and when are we not? What role do we play in these ongoing stories? Do we now need to be in a state of constant mobilization, on our guard against online attack, violent language and content, propaganda and surveillance? Who, and where, is the enemy? Who owns our digital and digitized stories? How will they be preserved in the future, and at what cost?

Hal Foster, reviewing the work of the visual artist Trevor Paglen, writes about the strangeness of this new digital world, wherein he (and Paglen) locate the crucial changes as being not so much to do with “the digital transformation of images...viral reproducibility and lost indexicality” but with “machine readability and image invisibility.” This “algorithmic scripting of information” ultimately distorts the lenses through which we experience and communicate the world.30 This is particularly thought-provoking in the context of war writing, where a certain tolerance for dehumanization and devaluing of projected and then, once war commences, identified enemies as well as civilians – especially women – and of the environment is expected and to some extent accepted by perpetrators, victims, and audiences alike. And all of this will be consumed by the omnipresent digital witnesses to, and commentators on, future war stories.

It is difficult to conceive of new forms of violence that could outpace those detailed in war writing and audiovisual forms to date, but we are already able to access them more easily, divorced from context. Foster is writing about AI and its biases, which could normalize the othering process even farther. To what extent will this trigger a rise in empathy amongst consumers of digital war culture? Hope Wolf has written of the need to place war stories as “vivid episodes in broader historical contexts” even as they can be “can be ‘hot’ in the sense of emotive and antagonistic.”31 As such they lend themselves to many social media-based debates. But online, the deeper, deterrent – or at least reflective – cultural value of war writing can be undermined by the unmooring of stories from facts and contexts, even as they are quantified and commercialized. Is the likelihood that the constant sharing and exposure of these narratives render them commonplace? And in so doing increases tolerances of violence against certain individuals because it is accepted as sporadic, fragmented, contained, and framed by screens?

Working in the offline about 1947 and the idea of war as the continuous present, Elisabeth Åsbrink writes about conflict in time: “Time is asymmetrical. It flows from order and disorder and cannot be reversed.” She offers an analogy: “A glass that falls on the floor and shatters cannot be restored to its own completeness. Nor is it possible to identify any point that is more now than any other one.” She then personalizes the narrative, posing the question: “Is this my heritage, my work? Is this my principal task – to gather rain, to gather shame? Groundwater poisoned by violence.”32 In fixating on the fragments, do we avoid a comprehensive reckoning with the scale of violence and suffering that stem from even the small wars that online media is now deployed to describe, even as we have so much information and testimony making up stories about past wars, with their legacies of violence, death, displacement, hate, suffering, and environmental destruction?

Endnotes

- David Barno and Nora Bensahel, “The U.S. Military’s Dangerous Embedded Assumptions,” War on the Rocks, April 17, 2018, https://warontherocks.com/2018/04/the-u-s-militarys-dangerous-embedded-assumptions/. ↩

- David Barno and Nora Bensahel, “War in the Fourth Estate,” War on the Rocks, June 19, 2019, https://warontherocks.com/2018/06/war-in-the-fourth-industrial-revolution/. ↩

- Lawrence Freedman, The Future of War: A History (London: Penguin, 2017). 286. ↩

- Robert A. Doughty, The Seeds of Disaster: The Development of French Army Doctrine, 1919–39 (Mechanicsburg, Penn.: Stockpole Books, 1985). 186-7. ↩

- Dave Maass, “Foreseeing FOIAs from the Future with Madeline Ashby,” in The End of Trust, vol. 54 (McSweeney’s, 2018), 318–25. 318. ↩

- Maass, “Foreseeing FOIAs from the Future with Madeline Ashby.” 323. ↩

- Kathleen Hall Jamieson, Cyberwar: How Russian Hackers and Trolls Helped Elect a President (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018). 218. ↩

- Karan Kanishk, “Inauthentic Israeli Facebook Assets Target the World,” Medium, May 17, 2019, https://medium.com/dfrlab/inauthentic-israeli-facebook-assets-target-the-world-281ad7254264. ↩

- Adam Entous and Ronan Farrow, “Private Mossad for Hire,” New Yorker, February 11, 2019, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/02/18/private-mossad-for-hire. ↩

- Ronan Farrow, “Harvey Weinstein’s Army of Spies,” The New Yorker, November 6, 2017, https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/harvey-weinsteins-army-of-spies. ↩

- Wilson, Peter, et al., “The European Fiscal-Military System 1530–1870 Project,” University of Oxford, accessed June 10, 2020, https://fiscalmilitary.history.ox.ac.uk. ↩

- Rebecca Roach, “Black Boxes,” King’s College London: Research and Innovation, n.d., https://www.kcl.ac.uk/research/black-boxes. ↩

- Kiril Avramov and Ruslan Trad, “Self-Appointed Defenders of ‘Fortress Europe’: Analyzing Bulgarian Border Patrols,” Bellingcat (blog), May 17, 2019, https://www.bellingcat.com/news/uk-and-europe/2019/05/17/self-appointed-defenders-of-fortress-europe-analyzing-bulgarian-border-patrols/. ↩

- Robert Gerwarth, The Vanquished: Why the First World War Failed to End, 1917–1923 (London: Allen Lane, 2016). 266. ↩

- Martin Conway, Pieter Lagrou, and Henry Rousso, Europe’s Postwar Periods - 1989, 1945, 1918: Writing History Backwards (London: Bloomsbury, 2019). ↩

- Robert Evans, “How the MAGAbomber and the Synagogue Shooter Were Likely Radicalized,” Bellingcat (blog), October 31, 2018, https://www.bellingcat.com/news/americas/2018/10/31/magabomber-synagogue-shooter-likely-radicalized/. ↩

- Robert Evans, “Ignore the Poway Synagogue Shooter’s Manifesto: Pay Attention to 8chan’s /Pol/ Board,” Bellingcat (blog), April 28, 2019, https://www.bellingcat.com/news/americas/2019/04/28/ignore-the-poway-synagogue-shooters-manifesto-pay-attention-to-8chans-pol-board/. ↩

- Paul Mozur, “A Genocide Incited on Facebook, with Posts from Myanmar’s Military,” New York Times, October 15, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/15/technology/myanmar-facebook-genocide.html. ↩

- Caitlin Werrell and Francesco Femia, “Update: Chronology of US Military Statements and Actions on Climate and Security: 2017–2019” (The Centre for Climate and Security, February 16, 2019), https://climateandsecurity.org/2019/02/16/update-chronology-of-u-s-military-statements-and-actions-on-climate-change-and-security-2017-2019/. ↩

- Geoffrey Parker, Global Crisis: War, Climate Change and Catastrophe in the Seventeenth Century (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2017). ↩

- “Strategic Trends Programme: Future Operating Environment 2035” (London: Ministry of Defence, December 14, 2015), https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/future-operating-environment-2035. ↩

- Patrick Tripp, “Diary,” London Review of Books, April 19, 2019, https://www.lrb.co.uk/v41/n10/patrick-tripp/diary. ↩

- Juan Cole, Informed Comment, n.d., https://www.juancole.com/. ↩

- Kate Aronoff, “The European Far Right’s Environmental Turn,” Dissent, May 31, 2019, https://www.dissentmagazine.org/online_articles/the-european-far-rights-environmental-turn. ↩

- Max Saunders, “Post-War Imagination and the Narrative of (Future) History in the To-Day and To-Morrow Book Series,” Correspondence: Hitotsubashi Journal of Arts and Literature 4 (February 2019): 127–51, https://hermes-ir.lib.hit-u.ac.jp/rs/bitstream/10086/30058/1/corres0000401270.pdf. ↩

- Roy Scranton, “When the Next Hurricane Hits Texas,” New York Times, October 7, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/09/opinion/sunday/when-the-hurricane-hits-texas.html. ↩

- Francesca Recchia, “Blogging the War: An Interview with John Little of the ‘Blogs of War,’” Muftah, September 5, 2013, https://muftah.org/blogging-the-war-an-interview-with-john-little-of-the-blogs-of-war/. ↩

- David Barno and Nora Bensahel, “War in the Fourth Estate,” War on the Rocks, June 19, 2019, https://warontherocks.com/2018/06/war-in-the-fourth-industrial-revolution/. ↩

- Clare Birchall, “Shareveillance: Subjectivity between Open and Closed Data,” Big Data and Society, December 2016, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951716663965. 5. ↩

- Hal Foster, “You Have a New Memory,” London Review of Books 40, no. 19 (October 11, 2018): 43–45, https://www.lrb.co.uk/v40/n19/hal-foster/you-have-a-new-memory. ↩

- Hope Wolf, “Mediating War: Hot Diaries, Liquid Letters and Vivid Remembrances,” Life Writing 9, no. 3 (2012): 327–36, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14484528.2012.689950. 335. ↩

- Elisabeth Åsbrink, 1947: When Now Begins, trans. Fiona Graham (London: Scribe, 2017). 250. ↩

Bibliography

- Aronoff, Kate. “The European Far Right’s Environmental Turn.” Dissent, May 31, 2019. https://www.dissentmagazine.org/online_articles/the-european-far-rights-environmental-turn.

- Åsbrink, Elisabeth. 1947: When Now Begins. Translated by Fiona Graham. London: Scribe, 2017.

- Avramov, Kiril, and Ruslan Trad. “Self-Appointed Defenders of ‘Fortress Europe’: Analyzing Bulgarian Border Patrols.” Bellingcat (blog), May 17, 2019. https://www.bellingcat.com/news/uk-and-europe/2019/05/17/self-appointed-defenders-of-fortress-europe-analyzing-bulgarian-border-patrols/.

- Barno, David, and Nora Bensahel. “The U.S. Military’s Dangerous Embedded Assumptions.” War on the Rocks, April 17, 2018. https://warontherocks.com/2018/04/the-u-s-militarys-dangerous-embedded-assumptions/.

- Barno, David, and Nora Bensahel. “War in the Fourth Estate.” War on the Rocks, June 19, 2019. https://warontherocks.com/2018/06/war-in-the-fourth-industrial-revolution/.

- Birchall, Clare. “Shareveillance: Subjectivity between Open and Closed Data.” Big Data and Society, December 2016, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951716663965.

- Cole, Juan. Informed Comment, n.d. https://www.juancole.com/.

- Conway, Martin, Pieter Lagrou, and Henry Rousso. Europe’s Postwar Periods - 1989, 1945, 1918: Writing History Backwards. London: Bloomsbury, 2019.

- Doughty, Robert A. The Seeds of Disaster: The Development of French Army Doctrine, 1919–39. Mechanicsburg, Penn.: Stockpole Books, 1985.

- Entous, Adam, and Ronan Farrow. “Private Mossad for Hire.” New Yorker, February 11, 2019. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/02/18/private-mossad-for-hire.

- Evans, Robert. “How the MAGAbomber and the Synagogue Shooter Were Likely Radicalized.” Bellingcat (blog), October 31, 2018. https://www.bellingcat.com/news/americas/2018/10/31/magabomber-synagogue-shooter-likely-radicalized/.

- Evans, Robert. “Ignore the Poway Synagogue Shooter’s Manifesto: Pay Attention to 8chan’s /Pol/ Board.” Bellingcat (blog), April 28, 2019. https://www.bellingcat.com/news/americas/2019/04/28/ignore-the-poway-synagogue-shooters-manifesto-pay-attention-to-8chans-pol-board/.

- Farrow, Ronan. “Harvey Weinstein’s Army of Spies.” The New Yorker, November 6, 2017. https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/harvey-weinsteins-army-of-spies.

- Foster, Hal. “You Have a New Memory.” London Review of Books 40, no. 19 (October 11, 2018): 43–45. https://www.lrb.co.uk/v40/n19/hal-foster/you-have-a-new-memory.

- Freedman, Lawrence. The Future of War: A History. London: Penguin, 2017.

- Gerwarth, Robert. The Vanquished: Why the First World War Failed to End, 1917–1923. London: Allen Lane, 2016.

- Jamieson, Kathleen Hall. Cyberwar: How Russian Hackers and Trolls Helped Elect a President. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Kanishk, Karan. “Inauthentic Israeli Facebook Assets Target the World.” Medium, May 17, 2019. https://medium.com/dfrlab/inauthentic-israeli-facebook-assets-target-the-world-281ad7254264.

- Maass, Dave. “Foreseeing FOIAs from the Future with Madeline Ashby.” In The End of Trust, 54:318–25. McSweeney’s, 2018.

- Mozur, Paul. “A Genocide Incited on Facebook, with Posts from Myanmar’s Military.” New York Times, October 15, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/15/technology/myanmar-facebook-genocide.html.

- Parker, Geoffrey. Global Crisis: War, Climate Change and Catastrophe in the Seventeenth Century. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2017.

- Recchia, Francesca. “Blogging the War: An Interview with John Little of the ‘Blogs of War.’” Muftah, September 5, 2013. https://muftah.org/blogging-the-war-an-interview-with-john-little-of-the-blogs-of-war/.

- Roach, Rebecca. “Black Boxes.” King’s College London: Research and Innovation, n.d. https://www.kcl.ac.uk/research/black-boxes.

- Saunders, Max. “Post-War Imagination and the Narrative of (Future) History in the To-Day and To-Morrow Book Series.” Correspondence: Hitotsubashi Journal of Arts and Literature 4 (February 2019): 127–51. https://hermes-ir.lib.hit-u.ac.jp/rs/bitstream/10086/30058/1/corres0000401270.pdf.

- Scranton, Roy. “When the Next Hurricane Hits Texas.” New York Times, October 7, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/09/opinion/sunday/when-the-hurricane-hits-texas.html.

- Tripp, Patrick. “Diary.” London Review of Books, April 19, 2019. https://www.lrb.co.uk/v41/n10/patrick-tripp/diary.

- Werrell, Caitlin, and Francesco Femia. “Update: Chronology of US Military Statements and Actions on Climate and Security: 2017–2019.” The Centre for Climate and Security, February 16, 2019. https://climateandsecurity.org/2019/02/16/update-chronology-of-u-s-military-statements-and-actions-on-climate-change-and-security-2017-2019/.

- Wilson, Peter, et al. “The European Fiscal-Military System 1530–1870 Project.” University of Oxford. Accessed June 10, 2020. https://fiscalmilitary.history.ox.ac.uk.

- Wolf, Hope. “Mediating War: Hot Diaries, Liquid Letters and Vivid Remembrances.” Life Writing 9, no. 3 (2012): 327–36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14484528.2012.689950.

- “Strategic Trends Programme: Future Operating Environment 2035.” London: Ministry of Defence, December 14, 2015. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/future-operating-environment-2035.