Nether Worlds: Imagination, Agents, and Dark Acts

Virtual is not necessarily synonymous with digital: Brian Massumi argues for a clear distinction: “[a]ll arts and technologies... envelop the virtual in one way or another. Digital technologies in fact have a remarkably weak connection to the virtual, by virtue of the enormous power of their systematization of the possible.”1 But what happens to imaginative agency when bodies become disembodied digital objects? An unusual play about the digital future tackles the ethics of virtual imagining. The Nether (2013) by Jennifer Haley proposes a dystopian digital world. Its formal setting is discomfiting: “Time/ Soon.” Time Out was cheerful: “Forget Kim Kardashian’s bum – this is true internet horror.”2 Most critics said the play was deeply disturbing. It begins with a detective interrogating a man, Sims, who has a server in a secret location. This character’s name evokes a meta-level of imaginative agency, since The Sims (2000–) is the world’s best-selling life simulation video game: a digital analog becomes a metaphor for an analog world in digital form. Sims’s name also cleverly evokes a sim card, or storage identification module, used to store an international mobile subscriber identity which authenticates a mobile phone or computer user; simulacrum, an imitation of an object or person which may or may not have an original; and simulation, the process of imitation over time. Through Sims’s server, clients access The Hideaway, a virtual world which at first appears to be an innocent fantasy world of a Victorian house and gardens, with intensely realized sensual pleasures such as trees, no longer encountered in an environmentally degraded real world. The house holds a little girl, Iris, whose innocently childish games gradually reveal a darker purpose. Clients are pressured to hurt, rape, murder, and dismember her; their willingness to commit such heinous violence indicates their commitment to a seemingly impervious form of imagination. Other children in the house may have been similarly treated. Being virtual, however, Iris can reform; she is then revealed (spoiler alert) to be an avatar for an adult logged in on the server. Can vicious pleasure be harmless because it is virtual? Does virtual sadism absorb or create violent sexualities? These are questions which have been asked of older media, including books and film: The Nether reframes them for digital technologies.

In an interview in 2014, “Living Out Our Imagination,” playwright Jennifer Haley said she saw imagination as a kind of reality, adding “one of the things I try to do is to push against our assumption that living your life in a virtual reality is necessarily bad. Or that meeting people online is bad. I mean, we’ve got online dating.”3 We do: we also have laws against pedophile predation. Under the Sexual Offences Act of 2003, UK law defines grooming – intending child sexual abuse in any part of the world – as a crime. The play tests out questions of imaginative agency in terms of whether imagined forms of agency are harmful if the harm they produce is in the imagination. This is not a new question: feminist critics asked it repeatedly of visual technologies in the service of pornography – see in full Suzanne Kappeler’s The Pornography of Representation.4 The philosophical and political paradigm of freedom of expression which supplied – for some – a libertarian justification of pornography in the late twentieth century was reshaped in the digital era to accommodate a paradigm of sharing – indeed, digital forms of apparently shared agency appeared, like sexting. “Sexting is an important life skill. If the ability to pen a beautiful love letter got our grandparents the girl, today, having a baller sexting game can be the difference between a Tinder match that goes nowhere and being able to actually touch a person in real life. High stakes, people,” wrote Karley Sciortino in Vogue in 2015, blissfully unaware of giving us lesbian grandparents.5 “For your sexts to stand out, you must be creative,” she writes, supplying suggestions that reiterate poses and props from pornography, adapted for the digital age (think selfie sticks, auto-correct). The tension is between impervious imagination – what you imagine stays in your head – and leaky imagination – what you imagine has an effect on real behaviors. In a digital world where sharing is a standard default, how do your imaginings and what you share of them affect virtual and real behaviors?

In The Nether, sharing is multilevel. First there’s sharing the experience of being with others as an audience in a theater. Then there’s sharing the playwright’s text as it is performed (or read, which is a handy reminder of eighteenth-century anxieties about how reading novels might corrupt readers, especially women readers.) Then there’s sharing (or not) the point of view of characters and the twists of plot that ensue. But in this play, the characters test empathy to its limits – which makes for good drama, and interestingly self-reflective engagement. Do you think it is OK to act out fantasies? Do you think it is OK to act out violent fantasies? Do you think it is OK to act out fantasies featuring a little girl as an object of violence? Do you think it OK to act out fantasies featuring a little girl as an object of violence if the girl is virtual? What if virtual reality was so real that violence seemed real to perpetrators?

The Nether explores imagination as a domain so powerful it can reform identity. The disguised detective who interrogates Sims in order to shut down The Hideaway speaks wistfully of a father in a memory which may or may not be real, quoting a passage from a Theodore Roethke poem: “Which I Is I?”6 Roethke’s poem “In a Dark Time” focuses on a profound tangle of desire, emotions, sensations, and identity, all also informing the world of The Hideaway. Imagination’s perverse creations in that theatrically openly secluded place are mirrored in the “real” world, where the detective turns out to have her own reasons to pursue the patriarchal father, Papa, aka Sims, who runs the virtual world. Besides being a complex father figure of Freudian attraction, Papa is also a capitalist figure whose motives include profiteering from his clients’ gratification as their desires are given shape and serviced. To top off symbolic complexity, that gratification is cast in various discourses which coexist in tension: as temptation, with echoes of religious prohibition; as rational displacement, in that characters are acting out troubling desires virtually, hence with apparently no consequence in any real world; as rediscovery of sensual pleasure which is hardly possible, ironically, in an unvirtual world where nature has all but disappeared. The porosity of pleasure is exemplified by Papa using his profits to purchase real sources of sensation – wine made from grapes, an actual poplar sapling – as luxuries to consume offline. Porosity of responsibility appears in regulation of conversation in The Hideaway, where some words and ideas are banned from conversation between guest and child. The point is less to have ethical agency haunt relationships, although that consideration can’t be wholly shut out, so much as to protect the constructed imaginative world from a sense of its own constructedness.

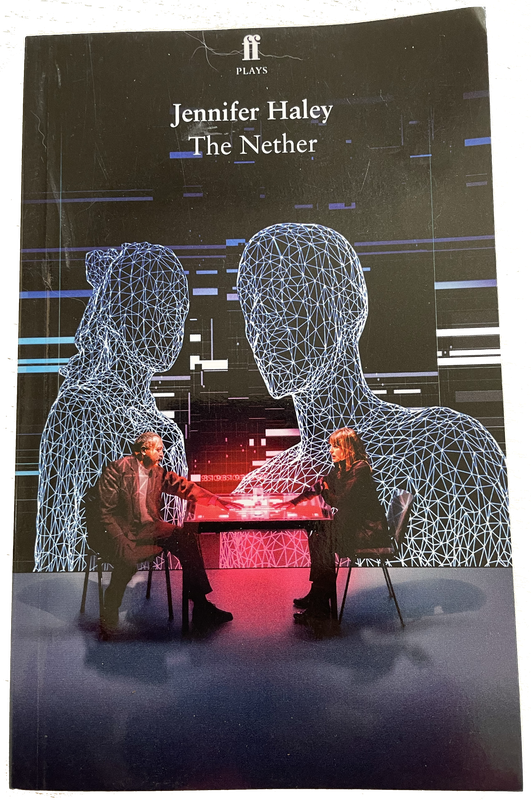

The Royal Court Theatre’s press release used an image – also the front cover image for the Faber & Faber edition of the play published in 2014 – in which sparkly outsize digital figures loom behind two of the actors. Their placing lightly ironizes gender, in that the male actor has behind him a female figure, and the female actor a male figure. The figures have networked skin and almost no facial features: literally scintillating, they embody virtual possibilities. They are forms that make visible Pierre Levy’s insistence that the virtual is not the opposite of the real, but one of four modes – virtual, actual, possible, and real.7 Levy’s observation that virtualization often involves materialization – here, the looming illuminated network of the figures behind the actors – is doubly enacted in a tension between virtual body and actor body, both engaged in establishing an audience relationship to make-believe. The virtual bodies here, the outsize figures, are arguably not virtual at all: they are real projections (the networked lights partly spill across the actors’ bodies). But they do also stand in for online personae, I think. Perhaps it is useful to read them in a different way as images that imagine play, an idea which finds a theorist in Susanna Paasonen. Rejecting the geotemporalities of play as “magic circles” (a model advanced by Johan Huizinga in his classic study of play, Homo Ludens), Paasonen instead conceptualizes play as “magical circuits [that] emerge and unfold across mundane spaces and locations, in all sorts of instances and occasions.”8 In The Nether, magical circuits are doubled, as sexualized play unfolds within a theatrical venue. One might call it play-within-a-play.

In her PhD thesis on Jennifer Haley, Michelle Yeadon establishes old similarities between theater and virtuality:

Haley writes plays specifically to make similarities she sees between theatrical and virtual worlds resonate. She connects both concepts through the eyes of role-play, as an actor. For Haley, by inhabiting “self-created fantasy worlds” theatre penetrates the essence of digital experiences: The way people inhabit avatars in a virtual world is not unlike the way actors inhabit characters onstage. Theatre is really appropriate for telling stories about identity and living out different characters in worlds that you’ve created. (“In Conversation with Playwright Jennifer Haley.” Interview by John Good)9

Role-play neatly connects theatrical function (you act a role) and virtuality (in acting, you pretend to be someone probably not yourself). Role-play also has a specific history in sexual practices, with “play” as noun and verb cropping up often. Susanna Paasonen, making play the playground (rather than sex) notes the complexity of its pleasure: “Play – sexual or other – is not fully free and voluntary, egalitarian and exclusively connected to the positive range of affect. Like human actions in general, it can be asymmetrical, risky, hurtful, violent and damaging in its reverberations and the pleasures it offers.”10 Discussing, among other things, online roleplay by minors, Paasonen notes the push-pull between imaginative experimentation in play and identity:

Sexual desire resists its congealment in and through identity categories for the very reason that it is not constant, predictable or knowable as such. At the same time, identity categories are crucial to how sexual desires circulate, how they stick and how people make sense of them, the world and their orientations within it. (546)

The theatricality of pornography and the virtuality of theatricality are not my concerns here; what I want to pick up is the ethical complexity of The Nether’s biggest twist, a reveal towards the end, when it turns out that the children being dismembered are actually avatars of adults. The investigating detective sends an agent to infiltrate the Nether world; “he” becomes allured, involved, and eventually traumatized by “his” complicity with its sexualized violence, necessary to maintain “his” alibi within the Nether world. Switching genders muddies critique of identity co-options; the choice to be an identity different from the one you start with is ostensibly open to all. Gender, age, even class are made fluid through imaginative double casting of actors recast within the play. Child characters of course have evil exemplars in their literary history – think of Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw (1898) or the demonically possessed twelve-year-old girl, Regan, in William Peter Blatty’s hugely successful and influential The Exorcist (novel 1971, film 1973). What shocks here is that behind the seductive child, Iris, is a college professor so allured by The Hideaway that he cannot bear rupture to the fabric of his illusions. He hangs himself rather than lose the possibility and the means of escape from himself. “I need to remind you this is a business,” says Papa to Iris when she appears to waver in favor of emotional attachment; business hard-headedness counters the pull of bodies and affections to each other, and punctures what might otherwise be immersion in a hyperreal equivalence, in Baudrillard’s terms, of signs with each other. What’s behind the seductive child is an idiom that carries traces of masks, potentially detachable surfaces; what’s revealed is that identity alteration into virtuality inhabits a digital dimensionality that makes even an idea of “within” too spatial to confine it.

Reality has caught up with some aspects of The Nether – “Time/Soon” – in the form of virtual reality pornography:

According to website Pornhub, views of VR porn are up 275 percent since it debuted in the summer of 2016. Now the site is averaging about 500,000 views (on Christmas Day in 2016, this number shot up to 900,000.)

By 2025 pornography will be the third-largest VR sector, according to estimates prepared by Piper Jaffray, an investment and management firm. Only video games and NFL-related content will be larger, it predicted, and the market will be worth $1 billion.11

Defenders of VR porn claim it services needs for lonely people out in an emotional cold – like The Hideaway’s clients. “Virtual reality has been nicknamed the empathy machine because it allows people to feel like they are truly connected to the action.”12 VR has been used to convey some of the effects of natural disaster and war (in some instances rousing indignation at inadvertent creation of disaster porn) in order to increase empathy for victims. The Head of Digital Content at the International Committee of the Red Cross, Ariel Rubin, discusses the difference between using virtual reality and augmented reality: “Virtual is deep, immersive and individualistic; whereas augmented is more of a shared experience because you can hold up a phone and show it to other people.”13

One critique of claims for VR as a technology of empathy proposes that empathy is being mistaken for emotions – a mistake convenient for a VR industry needing to counter a view of VR as solipsistic and privileged.14 The Nether puts the virtual real world of The Hideaway, all seductive pleasure with no apparent harmful consequence, against a regulatory world which is ethically imperfect, in that real fathers can abandon their children with lasting and damaging emotional consequence. Regulation seems to run counter to a freedom to imagine. Sims protests, “Now you want to tell them what to do. Or rather, what not to do. What not to think. What not to feel.… People should be free in their own imagination! That is one place, at least, where they should have total privacy!” (31) The detective, Morris, rejects his argument: “There is a line, even in our imagination.” That line is underlined through sensorial range and degree: “You don’t just offer images of children. You provide the sound and the smell and the touch of them.” (32) Aural and haptic sensations can increasingly be experienced online and, in contexts that link empathy, affect, embodiment, and tactility, often in strategic ways.15 Empathy though may be subservient to one subject’s pleasure or be co-opted by commerce. Thus https://www.immersion.com/technology/#touchsense-technology promises a quasi-orgasmic experience: “We will work with you to tune everything from vibration magnitude and duration to frequency and rhythm so that you can create a haptic experience that’s uniquely yours.” Gaming VR suits and gloves promise sensorial depth, as in https://youtu.be/600UX7jsanM.

Olfactory experience is harder to sell online, though digital scent technology is developing – for instance, e-noses – and research continues. (Avatar-based Second Life’s marketplace offers products claiming to evoke smell.16) The completely persuasive sensorium of the Hideaway, “Time/ Soon,” is less far off.

Some of the moral questions around VR apply to online, which to many people is an environment no less real than a physical world. Indeed, for many critics, absorption by online reality changes what reality means. In a 2014 web documentary made by the National Film Board of Canada and The Guardian, “Seven Digital Deadly Sins,” Bill Bailey describes online immersion as dangerously unaware of its own absorption:

the net provides us with this smorgasbord of options it’s this dark and unpredictable and dangerous thing and we just flit around it like plucking gummy bears off the back of a panther. We have no interest in the world around us, we’re just constantly swiping, flicking flicking flicking all the time oh there’s a picture of me… we’re like gadflies sipping nectar off deadly nightshade.17

The sense that images are a harmless form of imagination is tested by The Nether in relation to the ethics of virtual imagining, mirrored in the conflict between libertarian fantasy and child protection in a virtual world where morphologies of digital identity question whether you can or should escape moral responsibility. What forms of imaginative agency are permissible in relation to moral agency? The play’s epilogue is a short scene between Sims and the client who has acted as Iris – here under his own name, Doyle. Sims presents a cake – maybe – we don’t know if there is a cake or if it is a real cake, imagined, or a virtual cake or a virtual cake able to pass as real. It is, says Sims, made of ice that will never melt. Doyle says he can hear it, freezing and unfreezing. Sims says, “The cake reforms its crystal patterns.” The metaphor describes two circuits, I think: one is the closed loop of virtual imagining, here one in which adult can become child, again and again. Another is a subtler circuit of affect. Haley suggests in her Author’s Notes (at the end of the play’s text) that a young actress should play Iris, rather than a child actress who would take the audience out of the play (and be protected by law from physical or emotional harm, one might add.) Haley adds “A young actress adds warmth, which is critical to the chemistry of the play.” Uncertainty of warmth, or warmth unreciprocated, is what the play ends on:

Doyle: I love you.

Sims hesitates

Sims: You cannot know how much I love you.

End.

Ambiguous affection, or affect expressed ambiguously and with a grammar of repression and mystification (you cannot know), leaves Sims with agency in the form of the last utterance, and in the form of possible control over what the client/child can know about his feelings. Ice freezing and unfreezing is notably devoid of warmth; as chemistry, it is chilling (thaw is described as unfreeze, not melt). The cake, if it exists, appears to be a present, hence part of a gift economy, for which affect is often a given response – gratitude, happiness, loyalty are returned by the recipient to the giver. But we know that The Hideaway’s apparent largesse comes at a terrible cost: in real-world terms (Doyle has spent all his money on the Nether and is vulnerable to blackmail) and emotional bondage (Doyle is addicted to the Nether’s shapeshifting economy). Imaginative agency is thus confined to and constrained by the two closed circuit loops, which are hidden by the ostensible freedom of The Hideaway’s imagining.

I’ll end on two words, one old, one new. Nether can be a relatively neutral term for lower or downward (as in a trembling nether lip). It comes from Middle English, evolving from the Old English niᵱerian, meaning to depress, bring low, humiliate, oppress, accuse, condemn – all abasing terms. In British dialect it also means stunted and withered. None of these associations are cheerful, though it also survives more familiarly as nether parts, a euphemism for genitals. Sims argues that porn drives technology: “The most popular content when the Nether was called the internet? Porn.…I’ve been there…I’ve seen the cock bulges.” (30) The association between digital technologies and sexual gratification (hard drives?) creates a symbolic association between the Nether and dystopia, at least for anyone not as much in control of domains as Sims. Yet digital gaming makes light of the dark of nether in its coinage rez, noun and verb, a contraction of resurrect. You can die in a game and rez again. See examples – with conditions and restrictions – in World of Warcraft.18 Rezzing is what makes the Hideaway’s imaginative world seem less immoral: a child dismembered by a man with an axe just gets up again; it was all a game, in Sims’s terms. Ice crystals form and reform. But Nether morality requires imagination to be suspended, since the man thought he really was chopping up a child. Agency can undo imagination. There are indeed dark spaces in the sparkly digital network.

Endnotes

- Brian Massumi, Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation, Post-Contemporary Interventions (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2002). 137. ↩

- “The Nether,” Time Out, February 24, 2015, https://www.timeout.com/london/theatre/the-nether. ↩

- Jennifer Haley, Living Out Our Imagination: An Interview with Jennifer Haley, interview by Miranda Rizzolo, January 8, 2014, https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/living-imagination-interview-jennifer-haley/. ↩

- Susanne Kappeler, The Pornography of Representation (London: Polity Press, 1986). ↩

- Karley Sciortino, “Breathless: Mastering the Art of Sexting,” Vogue, accessed August 10, 2019, https://www.vogue.com/article/breathless-karley-sciortino-sexting. ↩

- Theodore Roethke, The Collected Poems of Theodore Roethke (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1966). ↩

- Pierre Levy, “Welcome to Virtuality,” Digital Creativity 8, no. 1 (1997): 3–10, https://doi.org/10.1080/09579139708567068. ↩

- Susanna Paasonen, Many Splendored Things: Thinking Sex and Play (London: Goldsmiths, 2018). 20. ↩

- Michelle Yeadon, “The Nether Worlds of Jennifer Haley – A Case Study of Virtuality Theatre” (PhD thesis, University of Oregon, 2018), https://scholarsbank.uoregon.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/1794/23726/Yeadon_oregon_0171A_12145.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. 30. ↩

- Susanna Paasonen, “Many Splendored Things: Sexuality, Playfulness and Play,” Sexualities 21, no. 4 (June 1, 2018): 537–51, https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460717731928. 540. ↩

- Alyson Krueger, “Virtual Reality Gets Naughty,” New York Times, October 28, 2017, sec. Style, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/28/style/virtual-reality-porn.html. ↩

- Notes on Blindness: Virtual Reality, accessed December 4, 2020, http://www.notesonblindness.co.uk/vr/. ↩

- Ariella Brown, “AR for Empathy: The Devastation of War,” DMNews.com, April 3, 2018, https://www.dmnews.com/customer-experience/article/13034609/ar-for-empathy-the-devastation-of-war. ↩

- Ainslie Sutherland, “No, VR Doesn’t Create Empathy. Here’s Why.,” BuzzFeed News, accessed August 10, 2019, https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/ainsleysutherland/how-big-tech-helped-create-the-myth-of-the-virtual-reality. ↩

- Teddy Pozo, “Queer Games after Empathy: Feminism and Haptic Game Design Aesthetics from Consent to Cuteness to the Radically Soft,” Game Studies 18, no. 3 (December 2018), http://gamestudies.org/1803/articles/pozo. ↩

- Pablo Vio and Jeremy Mendes, “Release the Snails!,” Seven Digital Deadly Sins: Sloth, accessed December 4, 2020, http://sins.nfb.ca/#/Sloth/Video. ↩

- Second Life Marketplace, accessed December 4, 2020, https://marketplace.secondlife.com/. ↩

- “Resurrect,” in Fandom: WoWWiki, 2005, https://wowwiki-archive.fandom.com/wiki/Resurrect. ↩

Bibliography

- Brown, Ariella. “AR for Empathy: The Devastation of War.” DMNews.com, April 3, 2018. https://www.dmnews.com/customer-experience/article/13034609/ar-for-empathy-the-devastation-of-war.

- Haley, Jennifer. Living Out Our Imagination: An Interview with Jennifer Haley. Interview by Miranda Rizzolo, January 8, 2014. https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/living-imagination-interview-jennifer-haley/.

- Kappeler, Susanne. The Pornography of Representation. London: Polity Press, 1986.

- Krueger, Alyson. “Virtual Reality Gets Naughty.” New York Times, October 28, 2017, sec. Style. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/28/style/virtual-reality-porn.html.

- Massumi, Brian. Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation. Post-Contemporary Interventions. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2002.

- Levy, Pierre. “Welcome to Virtuality.” Digital Creativity 8, no. 1 (1997): 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/09579139708567068.

- Paasonen, Susanna. “Many Splendored Things: Sexuality, Playfulness and Play.” Sexualities 21, no. 4 (June 1, 2018): 537–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460717731928.

- Paasonen, Susanna. Many Splendored Things: Thinking Sex and Play. London: Goldsmiths, 2018.

- Pozo, Teddy. “Queer Games after Empathy: Feminism and Haptic Game Design Aesthetics from Consent to Cuteness to the Radically Soft.” Game Studies 18, no. 3 (December 2018). http://gamestudies.org/1803/articles/pozo.

- Roethke, Theodore. The Collected Poems of Theodore Roethke. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1966.

- Sciortino, Karley. “Breathless: Mastering the Art of Sexting.” Vogue. Accessed August 10, 2019. https://www.vogue.com/article/breathless-karley-sciortino-sexting.

- Sutherland, Ainslie. “No, VR Doesn’t Create Empathy. Here’s Why.” BuzzFeed News. Accessed August 10, 2019. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/ainsleysutherland/how-big-tech-helped-create-the-myth-of-the-virtual-reality.

- Vio, Pablo, and Jeremy Mendes. “Release the Snails!” Seven Digital Deadly Sins: Sloth. Accessed December 4, 2020. http://sins.nfb.ca/#/Sloth/Video.

- Yeadon, Michelle. “The Nether Worlds of Jennifer Haley – A Case Study of Virtuality Theatre.” PhD thesis, University of Oregon, 2018. https://scholarsbank.uoregon.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/1794/23726/Yeadon_oregon_0171A_12145.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Time Out. “The Nether,” February 24, 2015. https://www.timeout.com/london/theatre/the-nether.

- “Resurrect.” In Fandom: WoWWiki, 2005. https://wowwiki-archive.fandom.com/wiki/Resurrect.

- Notes on Blindness: Virtual Reality. Accessed December 4, 2020. http://www.notesonblindness.co.uk/vr/.

- Second Life Marketplace. Accessed December 4, 2020. https://marketplace.secondlife.com/.