Emojis

Emojis are digital expressions of emotion that use visual forms of imagination. This article explores some of their antecedents, evolution, and cultures of meaning and reading.

Emojis can claim to be a global visual language. Utterly creations of the digital age, they have their own legitimizing body, encyclopedia, awards, and festivity – World Emoji Day, July 17, celebrated from 2014, promoted by the iCal icon used by Apple since 2002.1 As those dates indicate, emojis have rapidly colonized a range of social media platforms and different types of communications. They do so, moreover, despite some variations – on Apple an egg emoji is white, on Google, brown. Such variations evidently don’t impede recognition, and variability is even made into a comic plot of sorts in The Emoji Movie (dir. Tony Leondis, Sony and Columbia Pictures, 2017).

Emojipedia, founded in July 2013, was established by Jeremy Burge (an Australian) as the main reference site for emoji. It has eight categories:

Categories

😃 Smileys & People

🐻 Animals & Nature

🍔 Food & Drink

⚽ Activity

🌇 Travel & Places

💡 Objects

🔣 Symbols

🎌 Flags

Weathering some controversy – whether to replace a handgun with a water pistol, for instance – Burge remains a human authority on emoji and a key player in the approval system for new ones.

Before exploring the emoji lexicon, one might consider a longer history of pictorial languages and, indeed, a wide history of constructed languages, or conlangs. Among the proliferations are engineered languages (engelangs), auxiliary languages (auxlangs, used when two people don’t have a language in common), and artistic languages (artlangs) – and any of these can have fictional applications too. Writer and professor Sally Caves, a devotee of the field of conlangs and deviser of the well-regarded Teonaht, lists many intriguing examples at http://www.concavities.org/teonaht/teonaht.html. She celebrates the imaginative satisfactions of creating a new language, especially in tandem with creating imaginative worlds in which such languages can be naturalized. Literary exemplars include J. R. R. Tolkein, creator of the Elvish language, and – rather gloriously – the German abbess Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179), writer, composer, mystic, and polymath, who made up her own invented language, the Lingua Ignota, with an associated invented alphabet, the Litterae Ignotae.2

More contemporary examples of successful invented languages would include Robert Ben Maddison’s 1980 Talossa: its inventor, then aged fourteen, devised a micronation to go with it, a smart move which furthered its appeal. It still has an active community and a dedicated linguistic following.3

Sarah Higley showcased “magical” languages in a 2016 exhibition at the University of Rochester which displayed examples of conlangs and artlangs from the Middle Ages.

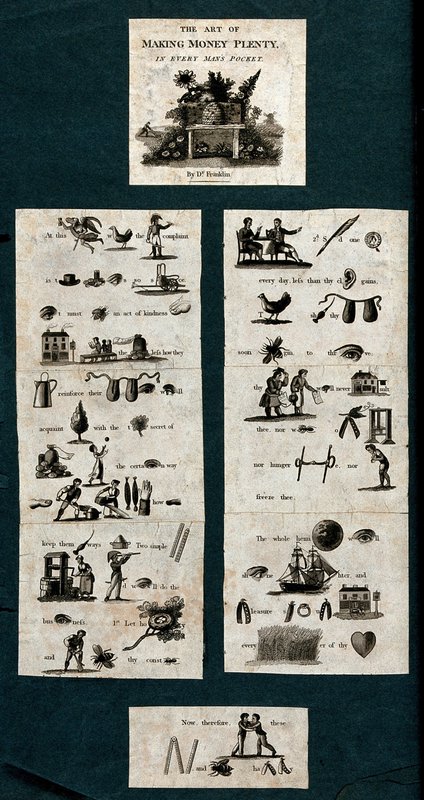

While emoji can be considered both conlang and artlang, they also seem to be doing something a little different. Turning words into pictorial form and providing pictures for emotions have long histories. Here one might look to the rebus, or puzzle language, in which pictorial forms of letters or words imitate the sound of words or phrases. This has a fascinating repertoire, from pictograms and hieroglyphs in ancient languages through medieval heraldry to modern puzzles.

Figure 2.

A simple example from 1865 proposes, May I see you home my dear?

This more ambitious example requires you to grasp a pictorializing language in which part of a word, or a whole word, is translated from sound to image, with the image echoing the sound. It seems slightly cumbersome now, but it shows how the rebus naturalizes play between pictorial and letter language. One unusual eighteenth-century survivor is a hieroglyphic Bible, with at least 630 rebus images in just its Old Testament. It is thought to have been made by an English seaman.

Pictorial languages are of course at least as old as hieroglyphs. Emojis have a more particular historical origin, dovetailing with emoticons. An emoticon, or emotional icon, was first used by Scott Fahlman on September 19, 1982 in a post to a message board. He proposed this character sequence to mark a joke

: -)

And this to mark not a joke

: - (

The idea caught on fast, because tone can be difficult to read in digital communications and because punctuating text with joke markers shows humor, a commodity with value in digital communications. Quite why that value arises is a complex topic; Freud probably explains it best with his theory of humor as the means of managing anxiety and embarrassment. Simpler to explain is the apparent difficulty of reading emotions at all. As a journalist put it in 2014,

what’s relatively recent is the overwhelming amount of electronic exchanges we have with people whose personalities we only know digitally. Without the benefit of vocal inflections or physical gestures, it can be tough to tell e-sarcastic from e-serious, or e-cold from e-formal, or e-busy from e-angry. Emoticons and exclamation points only do so much.4

The authors of a study of emoticons in Nordic workplaces propose that

Emoticons are still in widespread use both in messages between people whose personalities are known to each other and in workplace communications. One investigation proposes that emoticons function as contextualization cues, which serve to organize interpersonal relations in written interaction. They serve 3 communicative functions. First, when following signatures, emoticons function as markers of a positive attitude. Second, when following utterances that are intended to be interpreted as humorous, they are joke/irony markers. Third, they are hedges: when following expressive speech acts (such as thanks, greetings, etc.) they function as strengtheners and when following directives (such as requests, corrections, etc.) they function as softeners.5

There is a fine line, especially for linguistics scholars, as to whether emoticons are emotional in their own right or cues for emotions relevant to contingent materials. Or both. In either case, the power of emoticons to alter meaning points to possible imaginative agency on the part of the user, who chooses a relevant emoticon and makes it part of the message, and also on the part of the reader, who must recognize the emoticon and comprehend its inference. Lexicons of expressiveness are nothing new: in eighteenth-century familiar letters, underlinings, capital letters, dash punctuation, and even tear blots could all convey material import which affected readings. Emoticons’ relative restriction to a lexicon in which typographical signs make a face-like expression has not stopped them being globally adopted and adapted. Japanese kaomojis, which appeared also in the 1980s using slightly different typographic conventions, have cross-fertilized possibilities into an extensive and more or less global language, with some local variations (for example, Brazilians using emoticons favor accents.) Emoji itself encapsulates this cross-fertilization by adopting the Japanese term, e meaning picture and moji meaning letter or character, emoji, hence, meaning a picture word. It also perhaps echoes the English emotion sufficiently to imply a picture word for an emotion.

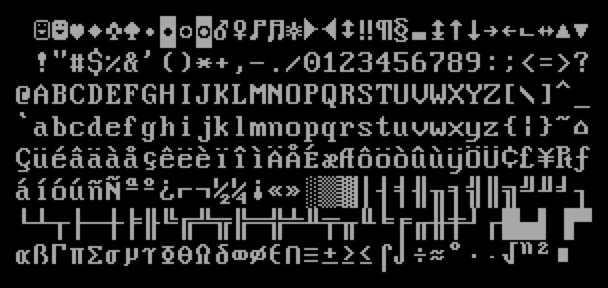

Meanwhile, a parallel development of the smiley face began to join up with emoticons. Originally developed by an American graphic artist, Harvey Ross Ball, the smiling face on yellow was meant to raise employee morale at an insurance company. Spreading through pre-internet popular culture (including being the icon of acid house culture in Britain in the 1980s), the smiley made it into the first personal computers, via the character set known as code page 437 of IBM PC.

Compare this to Unicode’s 2019 listing – in part, here6 – and it is evident that considerable evolution has taken place, both graphically and emotionally. From simple smiley and frownie, we now have an extensive vocabulary. We even have a major novel in emoji:

Emoji Dick (2013) is a crowdsourced and crowdfunded translation of Herman Melville’s Moby Dick (1851). The idea came from Fred Benenson, an early adopter of emoji who wanted to see how far they could go. Http://www.emojidick.com/ explains the process:

Each of the book’s approximately 10,000 sentences has been translated three times by an Amazon Mechanical Turk worker. These results have been voted upon by another set of workers, and the most popular version of each sentence has been selected for inclusion in this book. In total, over eight hundred people spent approximately 3,795,980 seconds working to create this book. Each worker was paid five cents per translation and two cents per vote per translation.

The intensive labour of emoji books explains why there are few such epics. One other is Book from the Ground: Point to Point7 by Xu Bing, an artist who took seven years to write it. Although the artist says anyone familiar with emoji can read it, it has not (yet) inspired imitators; it has inspired an explicatory book, The Book about Xu Bing's Book from the Ground 8, chronicling its making.

At the other end of the scale one might instance a simple image standing in for excess: thus Twitter’s Fail Whale, a whale being lifted by birds. It was originally designed by Yiying Lu as a feel-good image titled “Lifting the Dreamer,” and adopted by Twitter in 2008 to beguile users when its service was unable to cope with message volume. Retitled The Failwhale by a Twitter user,9 the Fail Whale acquired fan clubs and spin-off merchandising. It lasted till 2013, when Twitter’s ability to withstand the deluge of tweets in the US presidential election led executives to stop using it. “Though the whale hasn’t been formally retired, millions of the site’s users don’t even know it exists.”10 Such is the fragility of digital history that the Fail Whale, a pioneer of visual language in error pages, can disappear.

Not quite an emoji, the whale and its bird friends nonetheless convey an emotion. In the words of its designer Lu: “Birds in real life are never going to lift a whale, but in this picture it’s presented and it’s very affirming. It’s kind of like an impossible dream come true. People like something that makes them happy, makes them smile.” 11

Annoyance at a crashed platform is redirected into pleasure by an image that presents a condensed emotion, like an emoticon.

Although emoji are presented as a finished product, some people have wished to enhance them with sound. “For many people, hearing is a way of seeing,” says one Brazilian company12 http://emotisounds.com.br/?lang=en (which then invites you to watch a video); they offer a sound plug-in to a text reader for blind people which enables audio to replace verbal descriptors of laughter or tears. Promoters also stress extra comic value from emotisounds. The designer of one suite of sounds featuring cartoon-style comic voices describes texting without them as emotionless (sic!) whereas texting with sound is “a dynamic and often hilarious new mode of messaging.”13 Another suite uses mostly what one might call musical instruments with comic possibilities – horns, trumpets, xylophone – for brief exclamatory sounds.14 Yet, although emotisounds draw on natural, universal body language (laughter, farting, sobbing), most users seem satisfied with emoji as an exclusively visual language.

The full history and usage of emojis is a topic too big to encompass here: instead, I want to explore some instances of emojis in relation to their evolution. One feature to pause on is that if emojis are so expressive, why is there a supportive industry explaining how to use them? In 2015, Fred Benenson’s How to Speak Emoji15 went into paperback with this blurb:

For anyone who doesn’t know a smiley from a big red heart, a thumbs-up from a toilet symbol, a poo from two blonde girls dancing – this is the first book that will teach you HOW TO SPEAK EMOJI.

It may seem a stretch of imagination to suppose there are readers who can’t distinguish a poo from two dancers, but the implication is that despite the apparent graphic naturalism of emoji – a poo is represented by a picture of a poo – it is nonetheless a language which people need help to master.

Marcel Danesi’s The Semiotics of Emoji: The Rise of Visual Language in the Age of the Internet16 addresses the uses, grammar, semantics, variation, and spread of emoji, kicking off with the 2015 announcement by the Oxford English Dictionary that for the first time its word of the year was not a word but a pictogram: the emoji known as Tears of Joy.

😂

Inevitably it has a feline form: Cat with Tears of Joy.

😹

Danesi describes this as “a mind-boggling event in many ways, signalling that a veritable paradigm shift might have taken place in human communications and even human consciousness.”17 It was certainly good publicity for OED, banishing stuffiness by seeming on trend. Danesi’s account of emoji places them as a visual language equivalent to discourse structures in spoken exchange: “the ‘control of emotions,’ so to speak, is a primary discourse function of some, if not most, emoji. They also suggest that conveying one’s state of mind (opinion, judgment, attitude, outlook, sentiments, etc.) is a basic need in discourse exchanges.” Borrowing from Jakobsonian linguistics, “emoji usage entails emotivity (consciously or unconsciously) in addition to the phatic function.” What you see is what someone might express in verbal and nonverbal ways in conversation to convey their state of mind. Danesi’s own use of quotations around “control of emotions” and his gesture to approximation in “so to speak” show him using a version of discourse structures, consciously or unconsciously, that are recognized in academic language. If you can recognize “scare quotes,” you should have no trouble identifying emoji.

How do new emoji come about? Officially through Unicode: you need to submit a proposal, explaining the case. Unicode gives a list of all the requests received at https://unicode.org/emoji/emoji-requests.html.18 Many have been approved; some languish, often for want of full proposal information; some are declined.

Guess which these category these are in: humanoid unicorn, healthy poo, hangover. Or these: man fairy, microbe, Mrs. Claus.

The first three were declined; the second three were accepted. Unicode’s reasoning appears mysterious. Why falafel but not hummus? Why sick pile of poo but not healthy poo? Why microbe but not germ? The answers depend on a suggestion satisfying a long list of criteria. The most important are compatibility with high-use emoji in popular existing systems, such as Snapchat, Twitter, or QQ, and expected usage level. You need to have demand before supply, in other words. Some requests are turned down because they are too specific: thus

Pot of Food (these are two Apple alternatives) is expected to stand for cassoulet or sukiyaki. One of the criteria does mention “breaking new ground,” but otherwise the old literary criteria of new words serving new purposes is nowhere to be seen.

The idea of expanding a language on demand is interesting, especially given the range of sensibilities around the world that may take offense. I was taken aback to see Emojipedia’s video showing the 230 new emoji sanctioned in 2019: it has People Holding Hands and Women Holding Hands. “People” are all visualized as men, a lamentably regressive idea that ignores decades of feminism and feminist linguistics. So much for inclusive language, though in 2019 WhatsApp jumped ahead of Unicode (which caught up in 2020) to embed a trans flag in its own emoji set.

Similarly, after, in 2019, Google proposed third gender options for emojis which have previously had two – a change that conveniently could, although won’t necessarily, increase cross-platform compatibility – most platforms began to introduce gender-neutral emoji: see https://emojipedia.org/neutral/ for a list from February 2020, which opens:

👱 Person: Blond Hair

🧔 Person: Beard

🧑🦰 Person: Red Hair

🧑🦱 Person: Curly Hair

🧑🦳 Person: White Hair

and concludes:

🤹 Person Juggling

🧘 Person in Lotus Position

💏 Kiss

💑 Couple with Heart

👪 Family

Woman/person/man, it all turns on haircuts – which begs questions…

Emojipedia comments, “Gender isn't going away, it’s getting a third option…”19

Ideologies informing emoji include not only identity politics but cultural colonization. Americans, for instance, favor cookies, and in particular the chocolate chip cookie, known in the UK from 1956 onwards as a Maryland cookie, after the brand leader. In Britain biscuits are a playfully serious business: a protester against Donald Trump on his state visit in 2018 appealed to the Queen – outside Windsor Castle! – with a placard: "Dear Queen don't offer him the good biscuits."20

Under this rousing slogan are pictures of a custard cream – for some the yummiest biscuit in a traditional mixed tin – and a Rich Tea, a plain biscuit – for many, plain to the point of boring (sometimes a virtue). Anyone wishing to understand more about British devotion to biscuits and the peculiarly intense culture around them can consult a long-running, biscuit-devoted website: http://www.nicecupofteaandasitdown.com/news/?id=238. The protest poster uses a visual language which has two different biscuit icons (rectangular and round), with a value scale (good and bad) also linked to a gift economy (politely generous or morally disapproving); that triple layering helps create the joke (possibly one confined to Britain). The reader needs to recognize visual forms of nouns, and place them in a mixed language of pictures and words.

Possibly complicated by different biscuit preferences within the nation, biscuit emojis have not proved obvious, as one comment thread in particular reveals. In March 2017, someone posted a question on Mumsnet: “What is the Biscuit emoji for?”21 In the twenty-eight replies, responders patiently offered explanations: it means you think someone is being unreasonable or silly, said several, or it means no comment, with a “no comment” function nonetheless taking on the work of registering the presence of the person posting. One responder nailed the origin: in October 2009, the then Prime Minister Gordon Brown became the latest politician to participate in the live discussion forum of Mumsnet, where he was quizzed on topics including MPs’ expenses (a current scandal), banks, the environment, and his own health. As a lighthearted ending to the interview, Mumsnet rolled out a question other interviewees had been asked: What’s your favourite biscuit? Brown was floored and unable to answer. What became frivolously known as Biscuitgate was then taken as an instance of dithering, which detractors made much of as characterizing Brown’s politics in general. Twenty-four hours later, Brown announced he quite liked chocolate biscuits, but it failed to reverse a general judgment of failure.

It was evidently not obvious to Gordon Brown that expressing a biscuit preference, for all the dangers of giving offense, was an important part of online pleasantry and political populism. By 2017, what mattered most in the Mumsnet discussion was not factual accuracy about origins, but current usage. Hence some doubts about what a biscuit emoji meant: was taking the biscuit like taking the mickey? One responder said the biscuit, which in this case was an emoji apparently representing a jammy dodger, looked like flowers. Another expressed surprise: she thought the jammy dodger looked like an arsehole, and signified accordingly. Jammy Dodgers, also produced by Burtons, were the favorite biscuit of children in the UK in 2009, with 40 percent of the year’s sales consumed by adults22 If a shortbread biscuit sandwiched with red jam can be confused with a bunch of flowers or an arsehole, either UK biscuit eaters have weak eyesight or emojis are not as clear as they might be – a nice case of the separation of signifier and signified in semiotics. Another Mumsnet thread in April 2017, also on biscuits, discussed the jammy dodger as an emoji.23 Again there were cases of mistaken identity – one respondent thought the icon was a peach, another a cat’s bottom – and again more digitally literate respondents provided glosses: “I think it’s lost it’s original meaning along the way, now usually it’s posted on trolly and goady threads to mean ‘shut up’'’; “I also think it is used to place mark on a thread where a bunfight is imminent.” Other respondents suggested as synonym a face-based emoji:

🙄: “I think 🙄says it better than a biscuit.” But even face-based emoji can have opaque meaning. Of the Face with Rolling Eyes, approved by Unicode in 2015, Emojipedia puts up a warning flag and advises, “Appearance differs greatly cross-platform. Use with caution.”24

The way emojis draw primarily on American culture with some Asian influences means that biscuit doesn’t feature in standard emoji lexicons. Biscuits are subsumed into the American category of “cookie,” which is of course also familiar as a term to describe small packets of data sent from a website and stored on a user’s computer by the user’s browser while the user is browsing. Derived from a UNIX term, magic cookie,25 for a packet of data which a computer receives and sends back unchanged, it was adopted by a web browser programmer, Lou Montulli, in 1994.26 What seems to have been magic about the magic cookie was that it circulated unchanged – an equivalent of uneaten? Cookies, in turn, seemed harmless and familiar until privacy legislation finally made it plain that they entailed access to browser history and data, and enabled users to refuse them more easily.

Users understand how to get round some of the formal restrictions on emoji. There’s no icon for penis, so everyone uses the aubergine instead. When in 2015 Instagram enabled emoji to be used as hashtags, it excluded the aubergine. As Mashable UK reported,

It gets stranger, though. While using one eggplant emoji will not yield a hashtag, combining it with others such as two eggplants — or the equally suggestive peach — is fine. The banana, the corn and other phallic-shaped emoji were left free for users to tag at will.27

Users quickly established certain combinations – aubergine and peach – as firmly sexual terms. In 2015, Instagram banned the aubergine – now known officially also as Eggplant – leading to a campaign, #freetheeggplant. Creative uses include Jesse Hill's music videos made entirely of emoji. One for a Beyonce song ran foul of copyright, but you can see another here.28

Sex-related emoji also inspired designs for vibrators.29

“Today, there are now more than 1,800 emojis, which are estimated to be used by more than 90% of the world’s online population. …for most, emojis offer not a substitute for the written word, but a complement, lending brevity or wit, irony or joy, to a text message.”30

Yet this curiously successful pictographic language (the first components of which were designed by Shigetaka Kurita in the 1990s31) evolves in mysterious ways.

A pile of poo was included in Google’s 2008 expansion of emoji because the concept was popular with users in Japan, where it already had a traditional meaning of good luck. Given eyes and a mouth, it became almost as widely adopted as the smiley face. But the full anthropomorphic variables for face emoji – smiling, frowning, laughing, winking – were not transferred or extended to poo equivalents. A proposal they should be32 led to a row at Unicode, by 2017 the official gatekeeper.

Typographers Michael Everson and Andrew West are leading the fight against the depressed feces. “The idea that our 5 committees would sanction further cute graphic characters based on this should embarrass absolutely everyone who votes yes on such an excrescence,” Everson wrote in a memo in October. “Will we have a CRYING PILE OF POO next? PILE OF POO WITH TONGUE STICKING OUT? PILE OF POO WITH QUESTION MARKS FOR EYES? PILE OF POO WITH KARAOKE MIC? Will we have to encode a neutral FACELESS PILE OF POO?” …

West backed him up with a similarly capitalized memo. “I personally think that changing PILE OF POO to a de facto SMILING PILE OF POO was wrong, but adding F|FROWNING PILE OF POO as a counterpart is even worse. If this is accepted then there will be no neutral, expressionless PILE OF POO, so at least a PILE OF POO WITH NO FACE would be required to be encoded to restore some balance.”33

It seems necessary to consult Freud here, since he theorized so elegantly the significance of defecation in the development of sexuality and its centrality to an anal phase. As a child learns continence, it also learns the pleasure of control and relaxation of control, which becomes an associated erotic pleasure. Rather than return to the anal phase per se, it may be more relevant to note the possible significance of note 15 in Freud’s discussion of infantile sexuality. Referring to his own study of a five-year-old boy with a phobia (a case later well known as Little Hans), Freud commented that it

has taught us something new for which psychoanalysis had not prepared us to wit, that sexual symbolism, the representation of the sexual by non-sexual objects and relations–reaches back into the years when the child is first learning to master the language.…

we learn that children from three to five are capable of evincing a very strong object-selection which is accompanied by strong affects.34

Mastering the language, a strong-object selection, and strong affects characterize the divisions over anthropomorphizing feces – and possibly also account for Everson and West’s unusually emphatic use of capital letters? When the language being mastered is emoji, rather than German or English, and the emoji in question is a pile of poo, no wonder that giving it a range of affect was contentious, since that could complicate, at least, the development from anal to genital sexuality. That the one emotion allowed to emoji poo is happiness is satisfactorily regressive to users, in that it returns them to the satisfactions of the anal phase without necessarily disturbing conscious cultural meanings, like the Japanese symbolism of good luck. (There is incidentally a relatively global superstition that a bird crapping on you is good luck.) As emoji appear in merchandise, inferences become more explicit, and common denominator meanings firmed up. You can buy a “Plush Smiling Poop Emoji Pillow,” an item whose description as soft, durable, decorative, and easy to clean is suggestively evocative of Freudian pleasure in feces. Not coincidentally, the marketing frame is infantile: “Wrap it up and give it as a child’s gift, gag gift, novelty gift, joke gift, funny gift.”35

In discussions during development of the pile of poo emoji, developers made these comments:

Ryan Germick, lead of Google Doodle team: I would reject the notion that it has one meaning. It’s a symbol in context, sort of like memes. You can do all kinds of funny things with it and use it with skill, but I guess the most common use is probably “that’s unfortunate, and I would like to punctuate my comment with a reiteration that I am displeased at what has just been expressed.” It’s the anti-like.

Takeshi: It says “I don’t like that,” but softly.

Darick: It struck me as a particularly flexible and effective emoji. It provides a way to say shit or crap in an email without explicitly typing the words, and it catches the reader’s attention in a way that smiley faces don’t. Most importantly, it always elicits a smile from the reader and the writer, which is ultimately the purest purpose of emoji: to add emotional expressiveness to written communication.

Ryan: I have often said that the Gmail emoticon is my proudest achievement. I knew that for years to come I could go to shopping malls and sign autographs.36

“A tear on its own means nothing. A tear shed in a particular mental, social, and narrative context, can mean anything. ‘Tears, idle tears,’ wrote Alfred Tennyson, ‘I know not what they mean.’”37 Is Freud any help in answering why Tears of Joy has been the most successful emoji and used ceaselessly worldwide? Tears wash away affect, he suggested, moving through metaphors of valves and other Viennese plumbing parts. Tears of Joy has been glossed as an expansion of or equivalent to LOL, Laugh Out Loud, a reaction, a sign-off phrase (though sometimes read as Lots of Love). What prompts digital subjectivity and communication to use so willingly this expression not only emotional, but something in addition to an emotion: a contradiction? An extreme? Is it an emblem of the body, otherwise lurking around online in uncertain or overdetermined ways? If we are so happy we weep, what sort of happiness is that in the holding place of a digital exchange?

The vehemence of barriers to prevent poo being given other emotions – which might otherwise seem like a standard exercise of imaginative agency – needs accounting for. Where psychoanalysis suggests it disturbs trajectories of development, another way to look at it might be through formalism, in that it turns an emoji into an emoticon. An emoticon combines emotion + icon, originally using keyboard characters and predating the internet ;). Emoticons now map many expressions onto a face38 and include icons for objects, overlapping with emoji.

Patterns of emoji usage can be tracked on social media (see https://emojitracker.com/). The data are so big as to defy comprehension: though you can follow usage trends by different platforms, like Google Trend, 5 billion emoji are sent daily on Facebook Messenger, and from 2015 half of all comments on Instagram included an emoji. That year too Unicode developed emoji with five different shades of skin color. “General-purpose emoji for people and body parts should also not be given overly specific images: the general recommendation is to be as neutral as possible regarding race, ethnicity, and gender.”39 But as Zara Rahman asks pointedly, “What is a neutral ethnicity, or a neutral race or gender?” The option of Simpson yellow is supposedly neutral, though in The Simpsons yellow characters were clearly not African American or Asian; they were almost as clearly white. Pointing out that only skin tone variants are available, not other facial feature variants, Rahman concludes, “Emoji skin tones are essentially like real life: White people still get to be the default, while many people of color feel left out of such rigid representation.” Discussing research that showed white people tended to choose not the palest white shade emoji but one darker (the tones comes from the Fitzpatrick scale, a standard in dermatology), Miranda Rosenblum condemned what she called “digital blackface,” or the way white people could step out of a racialized identity in ways not possible for people of color.40

On the gender choice available for hand gestures, researchers who mined 22 million tweets from the US reported that

some stereotypes related to the skin color and gender seem to be reflected on the use of these modifiers. For example, emojis representing hand gestures are more widely utilized with lighter skin tones, and the usage across skin tones differs significantly. At the same time, the vector corresponding to the male modifier tends to be semantically close to emojis related to business or technology, whereas their female counterparts appear closer to emojis about love or makeup.

In a more general perspective, these modifiers clearly increase the ambiguity of emojis, which were already shown highly ambiguous in many cases (Wijeratne et al., 2016; Miller et al., 2017). In fact, modifiers can render emoji meanings very far apart.41

Specters of stereotypes return in a study of how Britons used emoji when posting on social media about the heatwave of 2018.42 It used sentiment analysis software to analyze 135,710 posts from 82,902 Twitter users in the UK.

It reported:

Overall, the most used emojis to describe the heatwave, in order, were:

Key findings from the research include:

- Males were (slightly) more vocal about the heatwave, accounting for 51 percent of mentions. However, women use emojis significantly more (66 percent more) and display more emotion on social channels. 43 percent of male tweets were neutral, as compared to 36 percent of female posts.

In analyzing the differences, some oddities turn up. The happiest tweets (79 percent) were from Robin Hood’s Bay in Yorkshire – as well they might be, given its location close to an exceptionally beautiful part of the UK coast, and the grumpiest from the southeast (Watford, 44 percent negative). Swiftly leaving regional nuances aside, however, the report zeroed in on gender:

However, what is notable is that women used 66 percent more emojis than males.

The most used emojis by women were:

Tim Sanders, Data Science Director at IPG Mediabrands UK,continues: “It seems women are more comfortable in displaying high levels of emotion through their emojis, for example ‘Smiling Face with Heart Eyes’ and ‘Loudly Crying Face,’ whereas males tend to use more reserved representations.”

This finding was taken as sufficiently good information for IPG Mediabrands to angle gendered advertising differently in future marketing ploys. Findings were also taken as evidence that Britons were less stiff-upper-lip than traditional national stereotyping suggested and that Britons, famously obsessed with weather, were happier with high temperatures than had been assumed. The implications of climate crisis, or the likely difference in outlook between workers in hot cities and those able to stroll the Yorkshire coastline, are nowhere considered. Emojis are taken to represent sentiments that express people’s feelings straightforwardly. What you see is what you get.

A much more carefully considered study looked at emoji use in microcommunities – between partners, families, and friends. Following up with interviews, Wiseman and Gould’s research explored a hitherto little noticed (if at all) phenomenon, that of personalized emoji repurposing. “We define ‘repurposing’ as giving an emoji a specific and constant meaning beyond the initial ‘intention’ of the emoji designer; this meaning would be inaccessible to an outside observer without explanation.”43

Between partners, for instance, animal emoji might be adopted as a visual language of pet names. A penguin emoji thus stands for an endearment, rather than a penguin. Between friends there were numerous examples of jokes, typos, and comic misunderstandings which became referenced through emoji: “It's a sibling in-joke that no one gets except us, even if we explain it,” said one participant. Wiseman and Gould comment on these alternative purposings: “Although some emoji are indeed repurposed due to their renderings (see e.g., the Visual Affordance of Emoji subsection), many are repurposed for entirely different reasons, for example because they relate to something in the real world, or because they have been chosen randomly or ironically.” They note how emoji were used by participants to articulate things difficult to say and to create or strengthen emotional bonds through meanings shared only by the communicants. Emoji in these contexts act like a secret code or private language. An example from Mumsnet, the subject of a case study by Emma Newport44 shows how a group of friends and followers circulated a gin emoji, entirely unofficially, to commemorate the death of one of their circle through her favorite tipple.

In such ways repurposing involves acts of imaginative agency even when, as in one case in Wiseman and Gould’s study, the emoji are chosen randomly (the idea was to assign meaning to them after), since signifying randomness can be imaginative in its repurposing of a supposedly fixed language of sentiment. Wiseman and Gould conclude:

At times emoji are chosen at random to mean a specific concept, and equally some emoji are chosen purposefully because they convey the complete opposite of the intended sentiment. This implies caution is required when using machine learning techniques to understand the meaning and use of emoji.

Marketing companies take note!

As a visual language, emoji can be seen as part of a wider visual literacy. Its long history – including makers’ marks, coats of arms, altarpieces, and inn signs – predates modernity, but it became discussed as a concept in the 1960s, perhaps because of television.45 It is now part of everyday life to use devices that require visual literacy, as Ryan Germick, Google Doodle developer, remarks:

Ryan: It would be fascinating to see how many times in a day somebody processes an icon’s meaning. To be literate in modern culture you’re familiar with dozens, hundreds of icons — this thing to eject, this means low batteries, this means I have Wi-Fi. It’s not a language that’s taught in school, but it’s a language you have to know to survive. There’s a continuum of this whole visual way of comprehending the world and emoji are very much a part of that.46

Comprehend does double duty here: as a synonym for “understand and encompass fully.” How emoji comprehend the world raises two big questions (at least). For all their expansion and gradual take-up of shifts in identity politics, the official, Unicode-sanctioned icons are ultimately American-inflected. The icon for food is Hamburger. One might see sexual censorship as part of this: Apple users adopted the peach to represent buttocks, and many were not pleased when Apple changed the icon’s design so that it looked less like buttocks. Emoji are quite puritan, even Puritan. Second, the categories of emoji are really limited. Their language represents only slivers of experience and is most certainly not comprehensive as a system of representation even of emotions. Innovations relate to demand, which can be created artificially. In one instance from 2017, for example, a travel company asked tourists to invent emojis. Note that nobody asked local people for emojis to convey their experiences of tourists:

Travel website Booking.com has discovered in a study that holidaymakers often want to share their vacation experiences with others via messaging on mobile devices.

In response to this, and to celebrate the World Emoji Day on Monday (July 17), Booking.com has asked 18,000 travellers which new emojis they’d like to see. The top choices include images of people looking at a map, dressed in typical tourist gear, and taking a selfie.

Booking.com has brought these characters to life through illustrations and created a light-hearted petition for Unicode to include them as part of its current list.47

Screenshot of Booking.com petition page on change.org.

Included five images of proposed emojis.

Top, l – r. 1. Emoji with x’s for eyes, unhappily reading a part-folded map, held in yellow hands. 2. Smiling, wearing a beige sunhat with a red ribbon round it, sunglasses, a red shirt with yellow flowers and holding a camera. 3. Very smiley smiley face clutching mobile phone, coconut palm behind to our right, smiley sun behind to our left.

Bottom, l – r. 1. Smiley face wearing sunglasses, on a sun lounger, under a red and white striped parasol. There’s a cocktail next to the smiley face, also in the glass are a cocktail umbrella and a stick of fruit (orange and grape). There is also a book on the lounger. 2. Smiley face taking a blue flowery shirt and a green dress or top out of a brown suitcase.

Booking.com champions new “first 24 hour” holiday emojis.

Petition closed.

This petition had 327 supporters.

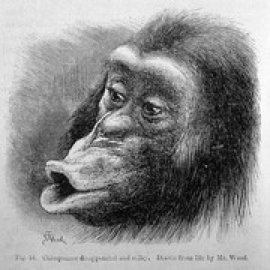

Emojis flatten out other important differences too. In Animals and Nature, for instance, which includes Weather as a subcategory, the animals represented are dominated by furry quadrupeds. Many have expressions that express humanoid rather than animal emotion, and in an explicit, Emojipedia-endorsed “cute” aesthetic. Compare the Google Monkey Face emoji

🐵

with a sensitive drawing from life of a chimpanzee, captioned “Chimpanzee disappointed and sulky.”

Of course disappointed and sulky may be projections of Victorian formulations of emotion. One of the artists commissioned by Darwin to prepare drawings was tasked with depicting a monkey who wrinkled his face when playing with the hair of his keeper. Darwin thought the monkey was chuckling. Joseph Wolf disagreed: “When interviewed later about the illustration, he admitted, ‘I never believed that that fellow was laughing, although Darwin said he was.’”48

Even so, emoji appropriate animals to represent human expressions beyond even anthropomorphism. The following feline emoji are classified by Emojipedia under Smileys and People:

😺 Grinning Cat Face

😸 Grinning Cat Face with Smiling Eyes

😹 Cat Face with Tears of Joy

😻 Smiling Cat Face with Heart-Eyes

😼 Cat Face with Wry Smile

😽 Kissing Cat Face

🙀 Weary Cat Face

😿 Crying Cat Face

😾 Pouting Cat Face

For marine life, emoji are sparse; they include seafood or dead marine life. Fish, blowfish, fish cake, fried shrimp, lobster, merperson (sic), crab, octopus, squid, shark, spouting whale, and sushi cover most of it, with fish standing for either salt or freshwater species. The lobster is not alive; as Emojipedia points out, its red color means it has been cooked. Its original version had one too few pairs of legs too, which was corrected.49

But one anatomical adjustment was all the lobster got, though Emojipedia did acknowledge another was needed: “Portland Maine’s Press Herald goes on to describe the tail as ‘grossly malformed’ but, well, at emoji-sizes we think the correction of the legs is enough to get this one over the line.”50

For all its composites and surface complexities like Tears of Joy, the emoji range of emotions is narrow, or much narrower than lived possibilities, though celebrators think otherwise. Gretchen McCulloch proposes that emoji restore our bodies to virtual communications: “We use emoji less to describe the world around us, and more to be fully ourselves in an online world.”51

There is room for imaginative agency in the use of emoji, but it is also a language whose gatekeepers include the big social media platforms where affordances limit uses and where consumer demand has to suit vested corporate and commercial interests. The gatekeepers are not unresponsive to consumer demand – thus Jeremy Burge responded to professional and world champion rock climber Sasha DiGiulian’s52 call for an emoji of a climber, for which she served as model. (See her account of the process at http://sashadigiulian.com/introducing-the-first-climbing-emoji/.)

In 2019, Emojipedia’s 230 additions represent differently-abled people and accessibility devices in newly explicit forms; they also represent the increased social purchase of BRIC economies (one of South America’s favorite drinks, maté (with an acute accent); a sari, a diya oil lamp, a Hindu temple; a tuk tuk or auto rickshaw).53

Emoji announced as under consideration for approval in 2020 as part of Unicode 13.0/Emoji 13.0 – which signaled a very probable release, given quite extensive Google-testing against trends – include a (subsequently released) disguised face.

“On EmojiRequest.com, a face emoji in disguise has been requested 22,580+ times.”54 With a gesture to Groucho Marx whose trademark moustache, eyebrows, and glasses have been kept familiar through sales as a novelty item, Disguised Face could be used for humor, to signal disguise or wanting not to be recognized, or even for finstagramming – that’s “fake + Instagram,” where users want to post “unflattering selfies or inside jokes without disrupting the image curation of their main account.”55 The specifications recommend it as a new concept, and one with unusually transparent ego media functionality:

Aside from generally communicating the idea of a physical disguise, the proposed emoji represents self-awareness of curated identity. While it acknowleges the online personas that have emerged from today’s social pressures, the Disguised Face emoji lightens up online conversations and serves as a reminder to not take yourself so seriously.

Endnotes

- “Calendar,” in Emojipedia, n.d., https://emojipedia.org/calendar/. ↩

- See Sarah L Higley, Hildegard of Bingen’s Unknown Language: An Edition, Translation, and Discussion (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007). ↩

- See Ma La Mha, A Complete Guide to the Talossan Language, 2nd English edition (Taloosa and USA, n.d.). ↩

- Eric Jaffe, “Why It’s So Hard to Detect Emotion in Emails and Texts,” Fast Company, October 9, 2014, https://www.fastcompany.com/3036748/why-its-so-hard-to-detect-emotion-in-emails-and-texts. ↩

- Karianne Skovholt, Anette Grønning, and Anne Kankaanranta, “The Communicative Functions of Emoticons in Workplace E-Mails: :-),” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 19, no. 4 (2014): 780–97, https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12063. 980-987;. ↩

- “The Unicode Standard, Version 15.0” (Unicode, 2022 1991), https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U1F600.pdf. ↩

- Xu Bing, Book from the Ground: From Point to Point (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2014). ↩

- Mathieu Borysevicz, ed., The Book about Xu Bing’s Book from the Ground (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2014). ↩

- See https://twitter.com/qrush/status/822613478. ↩

- Victor Luckerson, “Twitter IPO: How Twitter Slayed the Fail Whale,” Time, November 6, 2013, http://business.time.com/2013/11/06/how-twitter-slayed-the-fail-whale/. My thanks to Julie Rak for putting me in mind of the Fail Whale. ↩

- Yiying Lu, “Lifting a Dreamer (the Twitter Fail Whale) and Beyond,” YL Art. Branding, accessed December 5, 2020, https://www.yiyinglu.com/?portfolio=lifting-a-dreamer-aka-twitter-fail-whale. ↩

- See http://emotisounds.com.br/?lang=en. Accessed December 5, 2020. ↩

- Jim O’Brien, “Emojitones: Emojis with Sound. #StartUp #Apps #Emojis #iOS #Android,” TechBuzz Ireland, March 16, 2016, https://techbuzzireland.com/2016/03/16/emojitones-emojis-with-sound-startup-apps-emojis-ios-android/. ↩

- See https://icons8.com/sounds. ↩

- Fred Benenson, How to Speak Emoji (London: Ebury Press, 2015). ↩

- Marcel Danesi, The Semiotics of Emoji: Rise of Visual Language in the Age of the Internet (London; New York: Bloomsbury, 2017). ↩

- Danesi, The Semiotics of Emoji. 1. ↩

- “Emoji Requests,” Unicode Emoji, n.d., https://unicode.org/emoji/emoji-requests.html. ↩

- Jeremy Burge, “Google’s Three Gender Emoji Future,” Emojipedia (blog), March 13, 2019, https://blog.emojipedia.org/googles-three-gender-emoji-future/. ↩

- See https://twitter.com/davenolz/status/1017803948093255681. ↩

- hollyisalovelyname, “What Is the Biscuit Emoji For?,” Mumsnet, March 2, 2017, https://www.mumsnet.com/talk/site_stuff/2868243-what-is-the-biscuit-emoji-for. ↩

- Diane Lane, “Burton’s Foods Launches New Division for Food Service Snack Market,” Caterer and Hotelkeeper, November 30, 2009. ↩

- victoriousblunder, “To Not Understanding the Biscuit Emoji?,” Mumsnet, April 29, 2017, https://www.mumsnet.com/talk/am_i_being_unreasonable/2915875-to-not-understand-the-biscuit-emoji. ↩

- “Face with Rolling Eyes,” in Emojipedia, n.d., https://emojipedia.org/face-with-rolling-eyes/. ↩

- Eric S Raymond, “The Jargon File,” accessed August 10, 2019, http://catb.org/jargon/html/. ↩

- John Schwartz, “Giving Web a Memory Cost Its Users Privacy,” New York Times, September 4, 2001, sec. Business, https://www.nytimes.com/2001/09/04/business/giving-web-a-memory-cost-its-users-privacy.html. ↩

- Rachel Thompson, “The Cherry Emoji and 14 Other Emoji You Can Use to Sext,” Mashable, accessed August 10, 2019, https://mashable.com/article/emoji-sexting-peach-dead/. ↩

- Rebecca Greenfield, “The Creator Of This Amazing Beyonce Emoji Video Did It For Love,” Fast Company, March 17, 2014, https://www.fastcompany.com/3027773/the-creator-of-this-amazing-beyonce-emoji-video-did-it-for-love. ↩

- See https://emojibator.com/. ↩

- Simon Parkin, “Worried Face: The Battle for Emoji, the World’s Fastest-Growing Language,” The Guardian, September 6, 2016, sec. Art and design, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/sep/06/emojis-shigetaka-kurita-mark-davis-coding-language. ↩

- CNN 10, Who Invented the Emoji?, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ToAfDHDRu0U. ↩

- Nicole Wong et al., “Frowning Poo or Poo with Sad Face,” August 2, 2017, http://www.unicode.org/L2/L2017/17407-frowning-poo.pdf. ↩

- Madison Malone Kircher, “Sh*t Is Hitting the Fan over the New Poop Emoji,” Intelligencer, November 2, 2017, http://nymag.com/intelligencer/2017/11/unicode-consortium-fights-over-frowning-poop-emoji.html. ↩

- Sigmund Freud, Three Contributions to the Theory of Sex, trans. A. A Brill (New York: Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease Pub. Co., 1910). II. ↩

- Page no longer available, but originally at https://www.amazon.co.uk/EmojiGiftWorld-Smiling-Emoticon-Cushion-Decorative/dp/B01MRTQL7Z/ref=sr_1_2?keywords=emoji&qid=1560015884&s=books&sr=1-2. Accessed December 5, 2020. ↩

- Lauren Schwartzberg, “The Oral History of the Poop Emoji (or, How Google Brought Poop to America),” Fast Company, November 18, 2014, https://www.fastcompany.com/3037803/the-oral-history-of-the-poop-emoji-or-how-google-brought-poop-to-america. ↩

- Thomas Dixon, “Read It and Weep: What It Means When We Cry,” Aeon, accessed August 10, 2019, https://aeon.co/essays/read-it-and-weep-what-it-means-when-we-cry. ↩

- “Supplemental Symbols and Pictographs” (The Unicode Standard), accessed December 5, 2020, https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U1F900.pdf. ↩

- Zara Rahman, “The Problem with Emoji Skin Tones That No One Talks About,” The Daily Dot, November 23, 2018, https://www.dailydot.com/irl/skin-tone-emoji/. ↩

- Miranda Rosenblum, “👍🏿👎🏻: Emojis, Digital Blackface, and White Identity,” Digital America, April 11, 2018, https://www.digitalamerica.org/emojis-digital-blackface-and-white-identity-miranda-rosenblum/. ↩

- Francesco Barbieri and Jose Camacho-Collados, “How Gender and Skin Tone Modifiers Affect Emoji Semantics in Twitter,” Proceedings of the 7th Joint Conference on Lexical and Computational Semantics, 2018, 101–6, https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.18653/v1/S18-2011. ↩

- “Emoji Habits Shows How Brits Reacted to Heatwave,” Netimperative, September 3, 2018, http://www.netimperative.com/2018/09/emoji-habits-shows-how-brits-reacted-to-heatwave/. ↩

- Sarah Wiseman and Sandy J. J. Gould, “Repurposing Emoji for Personalised Communication: Why 🍕 Means ‘I Love You,’” CHI ’18: Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI ’18, April 2018, 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1145/3173574.3173726. 3. ↩

- Emma Newport, “Cytoarchitecture: Digital Dismembering and Remembering in Cyberspace,” European Journal of Life Writing 9 (2020), https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.21827/ejlw.9.36911. ↩

- Alan Michelson, “A Short History of Visual Literacy: The First Five Decades,” Art Libraries Journal 42, no. 2 (April 2017): 95–98, https://doi.org/10.1017/alj.2017.10. ↩

- Schwartzberg, “The Oral History of the Poop Emoji (or, How Google Brought Poop to America).” ↩

- http://www.nationmultimedia.com/detail/lifestyle/30320725, accessed August 15, 2019, but no longer live. Web archive available at https://web.archive.org/web/20170721043448/https://www.nationmultimedia.com/detail/lifestyle/30320725. For petition, see https://www.change.org/p/unicode-booking-com-champions-new-first-24-hour-holiday-emojis. ↩

- Philip Prodger, Darwin’s Camera: Art and Photography in the Theory of Evolution (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009). ↩

- Jeremy Burge, “Skateboard, DNA and Lobster Updated,” Emojipedia (blog), February 19, 2018, https://blog.emojipedia.org/skateboard-dna-and-lobster-updated/. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Gretchen McCulloch, Because Internet: Understanding the New Rules of Language (New York: Penguin, 2019). 14. ↩

- See https://youtu.be/oglD0lCSSQc. ↩

- Jeremy Burge, “230 New Emojis in Final List for 2019,” Emojipedia (blog), February 5, 2019, https://blog.emojipedia.org/230-new-emojis-in-final-list-for-2019/. ↩

- Mo Hy, “Proposal for New Emoji: Disguised Face” (Unicode Consortium, July 18, 2018), http://www.unicode.org/L2/L2018/18311-disguised-face-emoji.pdf. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

Bibliography

- Barbieri, Francesco, and Jose Camacho-Collados. “How Gender and Skin Tone Modifiers Affect Emoji Semantics in Twitter.” Proceedings of the 7th Joint Conference on Lexical and Computational Semantics, 2018, 101–6. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.18653/v1/S18-2011.

- Benenson, Fred. How to Speak Emoji. London: Ebury Press, 2015.

- Bing, Xu. Book from the Ground: From Point to Point. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2014.

- Borysevicz, Mathieu, ed. The Book about Xu Bing’s Book from the Ground. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2014.

- Burge, Jeremy. “Google’s Three Gender Emoji Future.” Emojipedia (blog), March 13, 2019. https://blog.emojipedia.org/googles-three-gender-emoji-future/.

- Burge, Jeremy. “Skateboard, DNA and Lobster Updated.” Emojipedia (blog), February 19, 2018. https://blog.emojipedia.org/skateboard-dna-and-lobster-updated/.

- Burge, Jeremy. “230 New Emojis in Final List for 2019.” Emojipedia (blog), February 5, 2019. https://blog.emojipedia.org/230-new-emojis-in-final-list-for-2019/.

- CNN 10. Who Invented the Emoji?, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ToAfDHDRu0U.

- Danesi, Marcel. The Semiotics of Emoji: Rise of Visual Language in the Age of the Internet. London; New York: Bloomsbury, 2017.

- Dixon, Thomas. “Read It and Weep: What It Means When We Cry.” Aeon. Accessed August 10, 2019. https://aeon.co/essays/read-it-and-weep-what-it-means-when-we-cry.

- Freud, Sigmund. Three Contributions to the Theory of Sex. Translated by A. A Brill. New York: Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease Pub. Co., 1910.

- Greenfield, Rebecca. “The Creator Of This Amazing Beyonce Emoji Video Did It For Love.” Fast Company, March 17, 2014. https://www.fastcompany.com/3027773/the-creator-of-this-amazing-beyonce-emoji-video-did-it-for-love.

- Higley, Sarah L. Hildegard of Bingen’s Unknown Language: An Edition, Translation, and Discussion. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

- hollyisalovelyname. “What Is the Biscuit Emoji For?” Mumsnet, March 2, 2017. https://www.mumsnet.com/talk/site_stuff/2868243-what-is-the-biscuit-emoji-for.

- Hy, Mo. “Proposal for New Emoji: Disguised Face.” Unicode Consortium, July 18, 2018. http://www.unicode.org/L2/L2018/18311-disguised-face-emoji.pdf.

- Jaffe, Eric. “Why It’s So Hard to Detect Emotion in Emails and Texts.” Fast Company, October 9, 2014. https://www.fastcompany.com/3036748/why-its-so-hard-to-detect-emotion-in-emails-and-texts.

- Kircher, Madison Malone. “Sh*t Is Hitting the Fan over the New Poop Emoji.” Intelligencer, November 2, 2017. http://nymag.com/intelligencer/2017/11/unicode-consortium-fights-over-frowning-poop-emoji.html.

- Lane, Diane. “Burton’s Foods Launches New Division for Food Service Snack Market.” Caterer and Hotelkeeper, November 30, 2009.

- Lu, Yiying. “Lifting a Dreamer (the Twitter Fail Whale) and Beyond.” YL Art. Branding. Accessed December 5, 2020. https://www.yiyinglu.com/?portfolio=lifting-a-dreamer-aka-twitter-fail-whale.

- Luckerson, Victor. “Twitter IPO: How Twitter Slayed the Fail Whale.” Time, November 6, 2013. http://business.time.com/2013/11/06/how-twitter-slayed-the-fail-whale/.

- McCulloch, Gretchen. Because Internet: Understanding the New Rules of Language. New York: Penguin, 2019.

- Mha, Ma La. A Complete Guide to the Talossan Language. 2nd English edition. Taloosa and USA, n.d.

- Michelson, Alan. “A Short History of Visual Literacy: The First Five Decades.” Art Libraries Journal 42, no. 2 (April 2017): 95–98. https://doi.org/10.1017/alj.2017.10.

- Newport, Emma. “Cytoarchitecture: Digital Dismembering and Remembering in Cyberspace.” European Journal of Life Writing 9 (2020). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.21827/ejlw.9.36911.

- O’Brien, Jim. “Emojitones: Emojis with Sound. #StartUp #Apps #Emojis #iOS #Android.” TechBuzz Ireland, March 16, 2016. https://techbuzzireland.com/2016/03/16/emojitones-emojis-with-sound-startup-apps-emojis-ios-android/.

- Parkin, Simon. “Worried Face: The Battle for Emoji, the World’s Fastest-Growing Language.” The Guardian, September 6, 2016, sec. Art and design. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/sep/06/emojis-shigetaka-kurita-mark-davis-coding-language.

- Prodger, Philip. Darwin’s Camera: Art and Photography in the Theory of Evolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Rahman, Zara. “The Problem with Emoji Skin Tones That No One Talks About.” The Daily Dot, November 23, 2018. https://www.dailydot.com/irl/skin-tone-emoji/.

- Raymond, Eric S. “The Jargon File.” Accessed August 10, 2019. http://catb.org/jargon/html/.

- Rosenblum, Miranda. “👍🏿👎🏻: Emojis, Digital Blackface, and White Identity.” Digital America, April 11, 2018. https://www.digitalamerica.org/emojis-digital-blackface-and-white-identity-miranda-rosenblum/.

- Schwartz, John. “Giving Web a Memory Cost Its Users Privacy.” New York Times, September 4, 2001, sec. Business. https://www.nytimes.com/2001/09/04/business/giving-web-a-memory-cost-its-users-privacy.html.

- Schwartzberg, Lauren. “The Oral History of the Poop Emoji (or, How Google Brought Poop to America).” Fast Company, November 18, 2014. https://www.fastcompany.com/3037803/the-oral-history-of-the-poop-emoji-or-how-google-brought-poop-to-america.

- Skovholt, Karianne, Anette Grønning, and Anne Kankaanranta. “The Communicative Functions of Emoticons in Workplace E-Mails: :-).” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 19, no. 4 (2014): 780–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12063.

- Thompson, Rachel. “The Cherry Emoji and 14 Other Emoji You Can Use to Sext.” Mashable. Accessed August 10, 2019. https://mashable.com/article/emoji-sexting-peach-dead/.

- victoriousblunder. “To Not Understanding the Biscuit Emoji?” Mumsnet, April 29, 2017. https://www.mumsnet.com/talk/am_i_being_unreasonable/2915875-to-not-understand-the-biscuit-emoji.

- Wiseman, Sarah, and Sandy J. J. Gould. “Repurposing Emoji for Personalised Communication: Why 🍕 Means ‘I Love You.’” CHI ’18: Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI ’18, April 2018, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1145/3173574.3173726.

- Wong, Nicole, Jennifer 8. Lee, Aphee Messer, Joel Rakowski, and Jane Solomon. “Frowning Poo or Poo with Sad Face,” August 2, 2017. http://www.unicode.org/L2/L2017/17407-frowning-poo.pdf.

- Netimperative. “Emoji Habits Shows How Brits Reacted to Heatwave,” September 3, 2018. http://www.netimperative.com/2018/09/emoji-habits-shows-how-brits-reacted-to-heatwave/.

- “The Unicode Standard, Version 15.0.” Unicode, 2022 1991. https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U1F600.pdf.

- Unicode Emoji. “Emoji Requests,” n.d. https://unicode.org/emoji/emoji-requests.html.

- “Face with Rolling Eyes.” In Emojipedia, n.d. https://emojipedia.org/face-with-rolling-eyes/.

- “Calendar.” In Emojipedia, n.d. https://emojipedia.org/calendar/.

- “Supplemental Symbols and Pictographs.” The Unicode Standard. Accessed December 5, 2020. https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U1F900.pdf.