Health Identity and Self-Representation

Both ideologically and discursively, the different types of content and self-representations participants shared on social media conveyed different health identities and determinants in the performance of what is “healthy.” This section examines some of the representational tools participants employed to enable such representations and explores why the life-stylization of health has become such an effective discourse in their healthy identity creation.

As Mennel et al. explain: “The social value attached to food, health and physical beauty has risen constantly in the second half of the twentieth century,” thus blurring the ideological boundaries between “health” and “lifestyle.”1,2,3,4,5 This was frequently framed through representations of healthy lifestyles, as demonstrated by Tim:

We visited the highest viewing platform in Europe so of course the first thing in my mind (other than the amazing view) was to get a pic of myself doing a handstand! This is something I am slightly obsessed about doing in special locations … It’s partly a way of expressing my sheer delight in a yogi style about being in such beautiful and special surroundings. Reasonable amount of feedback. I was already buzzing today from everything else but the likes, feedback etc. added to my pleasure for sure :) (Tim, Diary Entry, 34, M)

For Tim and many of the participants, styling representations of healthy behaviors in locations they visited was a common practice. For Tim enjoyment of the beautiful surroundings was enhanced by exercising in these locations, as well as by their provision of a scenic backdrop. Feedback from the online community, related to both exercising and the picturesque setting, also provided additional pleasure. As Lou described:

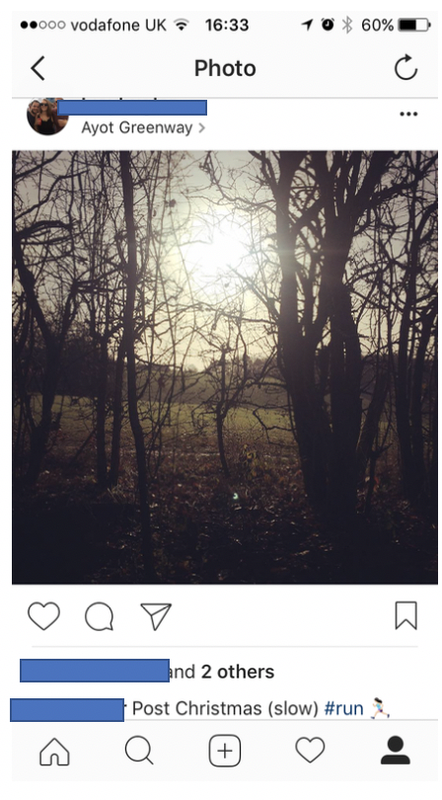

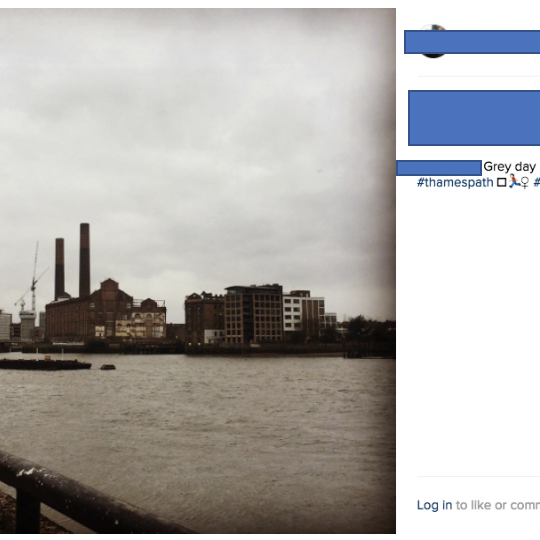

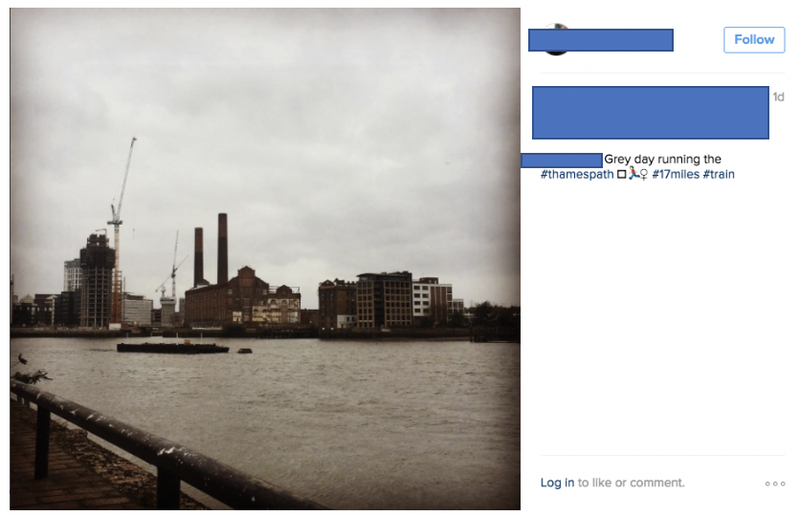

Distance I think is something that is interesting to share because actually the first question I’d always get was “oh my god how far did you run this weekend?” I’d say “16 miles” and they’d say, “that’s so ridiculous.” In terms of stats, speed and hills climbed, I find it a quite self-indulgent thing to share. It’s almost too much bragging. For me, my sharing was kind of influenced by the fact that I wasn’t necessarily staying out as late as other people, because I needed to go home because I needed to get up the next day. I wasn’t going to all the events I should have been going to or I’d be arriving late to it because I had to do a run in the morning. I think for me it was a bit more of that social side of sharing, being like “I am still doing cool stuff, I am still going to cool places.” (Lou, Final Interview, 29, F)

Sharers themselves often considered merely sharing screenshots from apps of (e.g., for the runners) self-tracked distances uninteresting. So, in an attempt to make their behaviors more relatable to others, participants life-styled their posts, taking and posting pictures of where they were going. In this way, we can see both the life-stylization of health occurring, as well as the collaborative aspect of individual health in these sharing spheres. These examples and practices extend Lucivero and Prainsack’s arguments around technologies as lifestyle products, which blur the boundaries between regulated medical devices and consumer products.6 Not only does capturing health become life-stylized with these ambiguously defined devices, but so too does exercise and evidence of health through representations on social media. Healthy behaviors are enacted by the individual, captured, and represented on social media for their own benefits, as well as for the community, who through feedback loops, simultaneously become a part of the health identity of the sharer online and offline (even when this desire to capture and share, for example, a “picturesque” running location, or aesthetically pleasing meal, detracts from the participants’ enjoyment of what they are actually doing). This in turn is “reconstituting the norms of living and living as a human subject,” through the use of technologies of the self.7

These processes affected and, in turn, encouraged the research participants, either through pressurizing influences or pleasurable motivations towards healthy offline behaviors. These life-stylizations of health also became a form of public diarizing, in the sense that they felt these represented their whole identity, not just their health. As Sophie asserted:

I guess it’s almost like a diary for yourself, a public diary even though you’re not going to be as honest in a diary online that is public and online about something that is private. (Sophie, Final Interview, 31, F)

Sharing health practices on social media, therefore, can be used as a form of public life and memory logging, enabling participants to look back not only over health developments, but also over all aspects of their lifestyles. The relationship between health and lifestyle became even more entwined with these data-sharing cultures, as lifestyle became representative of body image. As Tim wrote:

Over the previous 5 weeks snowboarding had taken over yoga as my main form of exercise. I particularly enjoyed making and sharing this vid as it was a culmination of weeks of riding, exploring and improving on my board. I was reflecting on what I’d been doing for the past month or so and was pleased with my progression in riding, fitness and video making skills! (Tim, Diary Entry, 34, M)

These carefully curated and mediated representations take a huge amount of the participants’ time and require technological literacy to achieve the desired effects. So, the life-stylization of health includes the documentation of fitness and skill progression, as well as technological fluency.

Sharing, surveying, and participating in lifestyle-related posts on Facebook and Instagram contributed to the participants feeling part of a community. Overall though, Facebook was considered more social, and Instagram more conducive to self-representation. These online communities do not always center around like-mindedness, or shared health and fitness goals, but often simply provide a sense of sociality and connection with others. For example, on New Year’s Day, Tim shared a photo of a handstand in his yoga practice. He included his Christmas tree in the background and an accompanying text stating he was “jumping into the new year.” In his diary, he continued:

Still felt hungover! Hehe! I felt happy to have shared my excitement at the new year beginning and as often with my posts hoped it may bring some good vibes to anyone not feeling quite so positive about things at that time. (Tim, Diary Entry, 34, M)

By documenting and sharing this particular pose on this date, Tim both metaphorically and physically demonstrated his positive mental and physical health, excitement, and enthusiasm about the year ahead. He was keen to represent a rounded and authentic self: still exercising despite his hangover. This construction of authenticity represents both an idealized and demonized health identity, which comprises both the good and bad, healthy and unhealthy self. Tim was perhaps comfortable representing himself in this way because his peers and online networks would similarly be celebrating New Year’s Eve, consuming alcohol and/or indulging in eating unhealthy festive foods. Thus, arguably his perception of potential judgment of unhealthy behaviors (drinking alcohol) was mitigated by others online and offline who were doing the same. Tim saw that his community was similarly sharing and representing their celebrations through Facebook and Instagram online.

Furthermore, this update of his New Year’s Eve celebrations and positive mental outlook acted as a representational tool to connect with his community by lifting others’ spirits and prompting interaction through social media. In his final interview, Tim explained that in the hours and days following his posting of this photo, he received many comments and likes from friends all over the world, updating him about their lives and discussing their celebratory activities, thus feeding his sense of community and sociality with friends near and far. The question remains, however, from this and previous examples: are these attempts at sociality through sharing content on Facebook or Instagram an attempt to overcome isolation in an individualized world? Lou examines these feelings of isolation and explains that:

When you run with someone, you’re like “someone was with me there, so I don’t need to tell anyone” which is quite weird, a little bit of the self-indulgence around social media I think. (Lou, Final Interview, 29, F)

Sharing, therefore, is important when engaging in solitary exercise: there is a desire to prove you’re doing something. This desire to log, document, and share is not felt on the same level with group activities, as the experience has been shared in the moment with other people. As Lou articulated:

I think on reflection it was part of that like almost social proofing of my life and initially just making sure that there was something engaging coming from me that other people could enjoy or engage in a little bit … I did almost see myself conforming to the “here’s what I did over the weekend, look how great my life is” mentality, and then after a while I was like “that’s not why you’re doing this stuff.” (Lou, Final interview, 29, F)

Lou described the process of sharing for the purpose of communication and sociality as a form of “social proofing.” In line with Wajcman’s work,8 she sought to demonstrate to her community that her life was interesting, full, busy, and social through social media posting, which enabled discussion prompts with friends and colleagues in her day-to-day life. Although used for different social purposes, Roy used his social media sharing to update online friends of his upcoming relocation:

The video isn’t particularly striking and it’s a pretty run-of-the-mill update, but it’s also sort of saying goodbye, which makes me a little sad. (Roy, Diary Entry, 26, M)

Whilst Roy’s hand-balancing friends had a Facebook group, they also met regularly at a local gym. Therefore, when he moved to a different city to start a new job, Roy shared a Facebook post as a way to say goodbye to those he had not managed to say farewell to in person at the gym. In his final interview, Roy was questioned in relation to his reasoning for saying goodbye to friends through posting a Facebook video:

That’s actually a really weird motivation to post something, like “I’m gonna say bye now but I’m not going to say bye to the people – I’m going to post something online.” It felt very natural, a marking point in your life where you’re moving somewhere else. Literally before that I spent every Thursday evening training with those people in that particular location, so it was maybe a way of making a real end to it. The same way someone might bring cake on their last day. (Roy, Final Interview, 26, M)

Roy likens his post to etiquettes of leaving a job and bringing in treats for colleagues on someone’s last day. Having spent regular time with his hand-balancing community members both at the gym and online through sharing posts, he felt it necessary to say goodbye both in person and online. It “felt natural” to do so, a normalized process to update others on personal life events both face-to-face and online, satisfying and maintaining social interactions in both spheres. During his final interview, Roy reflected on these hybrid social spheres:

After I moved here I didn’t post for four weeks. Then I kind of thought I should post so people know I’m not dead. I mean I don’t really have a following, like a fan-base or anything. People that follow me are my friends, so for them it’s like “I still exist, everything is fine, you don’t need to worry about me.” (Roy, Final Interview, 26, M)

A proper update for friends is, in other words, felt only to be achieved once a post is shared online. This does not always have to be health- or lifestyle-related, but any posting demonstrates the proliferation of the sharing discourse, whereby regular sharers feel as though they must maintain online self-representation: I post, therefore I am. Although many of the participants acknowledged these practices as trivial, they still followed these sharing etiquettes, motivated by pressures to be present on their chosen platform, signifying that posting means existing. Matt similarly recognized the prevalence of existing online contributing to his feelings of “being” in the community, especially after suffering an injury which meant he could not visit the gym:

Yeah it just goes hand in hand with it. It’s always happened ever since I started there. I’ve been an integral part of that boot camp since probably 2012, there’s four sessions a week, every session I go to we’re always tagged in it. It’s part and parcel of it, … Not being in it for eight weeks and then being back in, it was nice to be recognised again. They put my name in big letters on the picture and all the guys were commenting like “great to see you back.” (Matt, Final Interview, 41, M)

Matt’s gym has a Facebook group for their community, and once he returned after time out from his injury they tagged him in a post welcoming him back into their practices and fitness group. Online representations from the community made participants who had time out for injury or illness feel back involved and once again a part of that fitness community. These online community representations become as important as the actual fitness practices and the social, communicative workings of the community.

Endnotes

- S. Mennel, A. Murcott, and A. van Otterloo, The Sociology of Food: Eating, Diet and Culture (London: Sage, 1992). 36. ↩

- Carl Cederström and Andre Spicer, The Wellness Syndrome (Cambridge, UK: Polity, 2015). ↩

- William Davies, The Limits of Neoliberalism: Authority, Sovereignty and the Logic of Competition (London: Sage, 2015). ↩

- Tania Lewis, Smart Living: Lifestyle Media and Popular Expertise (New York: Peter Lang, 2008). ↩

- Phoebe V. Moore, The Quantified Self in Precarity: Work, Technology and What Counts (Abindgdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge, 2018). ↩

- F. Lucivero and B. Prainsack, “The Lifestylisation of Healthcare? ‘Consumer Genomics’ and Mobile Health as Technologies for Healthy Lifestyle,” Applied and Translational Genomics 4 (2015): 44–49. ↩

- T. P. Clough, “The Case of Sociology: Governmentality and Methodology,” Critical Inquiry 36, no. 4 (2010): 627–41. 11. ↩

- J. Wajcman, Pressed for Time: The Acceleration of Life in Digital Capitalism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014). ↩

Bibliography

- Cederström, Carl, and Andre Spicer. The Wellness Syndrome. Cambridge, UK: Polity, 2015.

- Clough, T. P. “The Case of Sociology: Governmentality and Methodology.” Critical Inquiry 36, no. 4 (2010): 627–41.

- Davies, William. The Limits of Neoliberalism: Authority, Sovereignty and the Logic of Competition. London: Sage, 2015.

- Lewis, Tania. Smart Living: Lifestyle Media and Popular Expertise. New York: Peter Lang, 2008.

- Lucivero, F., and B. Prainsack. “The Lifestylisation of Healthcare? ‘Consumer Genomics’ and Mobile Health as Technologies for Healthy Lifestyle.” Applied and Translational Genomics 4 (2015): 44–49.

- Mennel, S., A. Murcott, and A. van Otterloo. The Sociology of Food: Eating, Diet and Culture. London: Sage, 1992.

- Moore, Phoebe V. The Quantified Self in Precarity: Work, Technology and What Counts. Abindgdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge, 2018.

- Wajcman, J. Pressed for Time: The Acceleration of Life in Digital Capitalism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014.